In comparison to the cases of online violations reported before the COVID-19 outbreak, BIRN’s monitoring noted a significant rise in cases in which the perpetrators cannot be identified. The number of these cases increased tenfold on a monthly basis.

These unknown perpetrators have been creating Facebook pages, using the virus situation to persecute independent journalists and others, send fraudulent messages in order to destroy computer software systems or steal money, and creating fake website accounts to spread conspiracy theories or medical disinformation.

Unknown perpetrators have also been responsible for computer frauds, the destruction and theft of data and for making content unavailable using technical skills. Hungary had the most cases involving unknown perpetrators, mainly related to computer fraud.

Cases have also shown how states can be violators of digital rights and freedoms. The increased number of cases which ended in arrest or detention revealed the tendency of states to use more power than was necessary, particularly to arrest journalists and citizens for posts on social media.

From having double standards when it comes to reactions to fake news to using their authority to silence people, governments often acted against the interests of their own citizens. According to the monitoring findings, in almost 25 per cent of all cases, the state itself or a state official was described as the perpetrator of a violation of certain guaranteed rights or freedoms.

On the other hand, members of the public were the victims of violations in 126 cases.

Media regulations across the region have been tightened under states of emergency and journalists have been arrested on accusation of spreading misinformation about authorities’ responses to the spread of the coronavirus. Some countries, like Serbia, sought to centralise the dissemination of official information and banned certain media from regular briefings.

The first worrying legal initiative was noted in Croatia, where the government proposed a change to the Electronic Communications Act under which, in extraordinary situations, the health minister would ask telecommunications companies to provide data on the locations of users’ terminals. The legislative change is currently pending.

In Hungary, the Bill on Protection Against Coronavirus, giving the government almost total control of the flow of information about the pandemic, was adopted at the end of March. The Hungarian government also decided to limit the application of the EU’s General Data Protection Regulation, GDPR, and to extend the deadline for public institutions to provide data requested via freedom of information regulations from 15 to 45 days.

Romanian civil society organisations also drew attention to a lack of official transparency and the possibility of media freedoms being curbed by state-of-emergency provisions. Provisions enacted as part of the state of emergency to combat the spread of the coronavirus allowed the authorities to shut down websites that publish fake news and exempted the authorities from answering urgent inquiries from journalists. Access to a dozen websites has been blocked since then.

In North Macedonia, the media faced new procedures for the issue of work permits during coronavirus curfews. The government insisted that its pandemic measures would not affect the public’s right to information, but in practice, institutions were less responsive to freedom of information requests.

In general, there was a trend among many countries to suspend freedom of information requests.

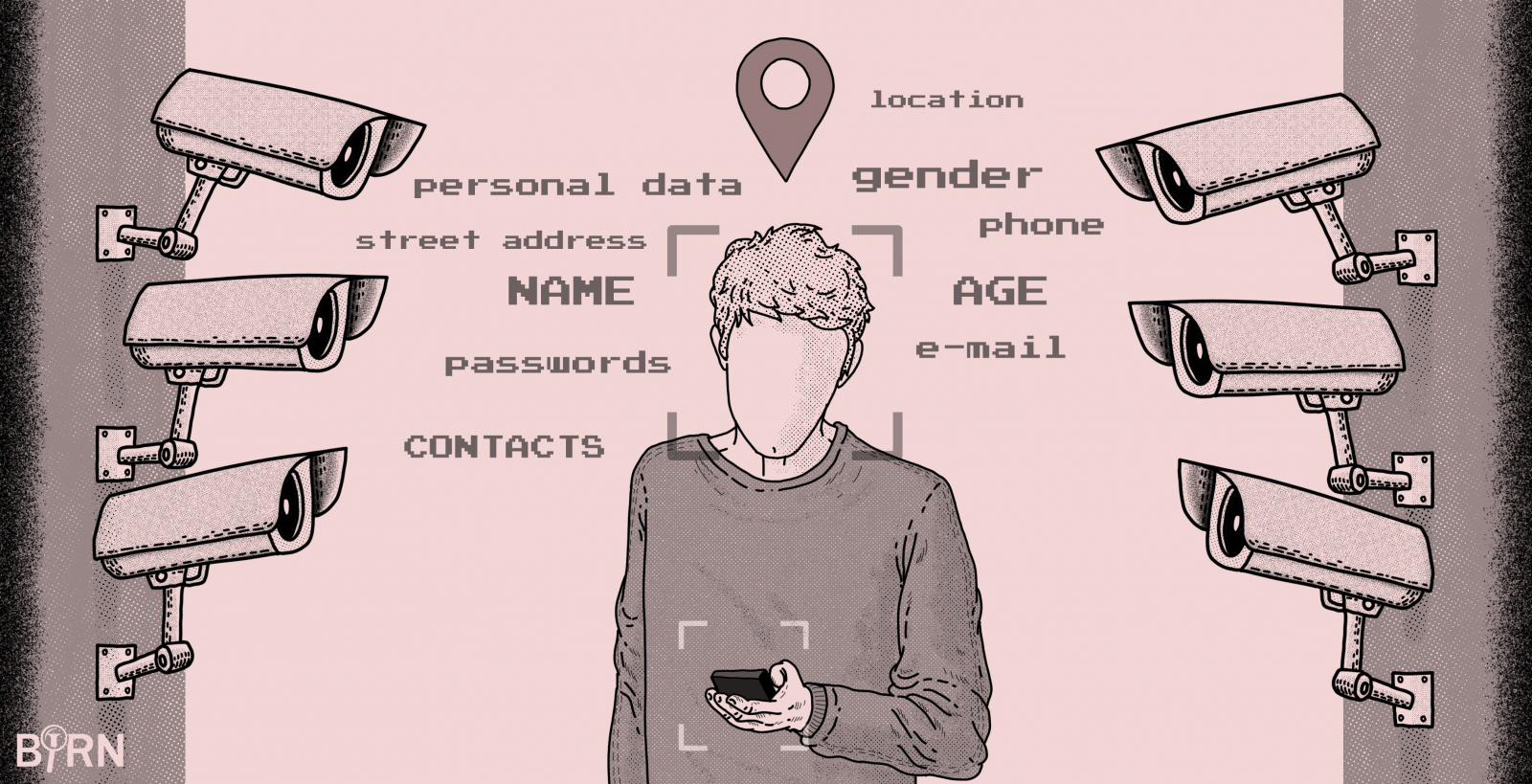

Digital rights, and rights to privacy and freedom of expression on the internet have all faced serious limitations and breaches in South-East and Central Europe. In the semi-democracies of the region, dominated by regimes with elements of authoritarianism, there is legitimate concern about disproportionate interference in citizens’ personal data and concern that recently-imposed measures are not properly tailored to achieve their objectives while causing the least possible damage to guaranteed rights.

Many people’s lives during this period have completely shifted to the online world, where harmful behaviour usually remains unnoticed by authorities preoccupied by offline violations.

During BIRN’s monitoring period, the lack of a human rights-based approach towards people in the digital environment led to discrimination, hate speech and threats. Although protection of basic human rights and fundamental freedoms should be guaranteed on the internet in the same way as it is offline, in practice we have seen an increase in the number of cases of online violations. The forms that those violations take have been evolving as well.

A lack of knowledge and understanding of the online space, and the subsequent lack of internet governance have opened a Pandora’s Box, allowing various state institutions to arbitrarily, partially and unequally interpret people’s online behaviour.

The intense nature of the battle for control of the narrative about the coronavirus has made meaningful oversight of online life and practices, and establishing accountability for online actions, harder than ever.

To read the detailed overview of our digital rights monitoring click here. For individual cases, check our regional database, developed together with the SHARE Foundation.