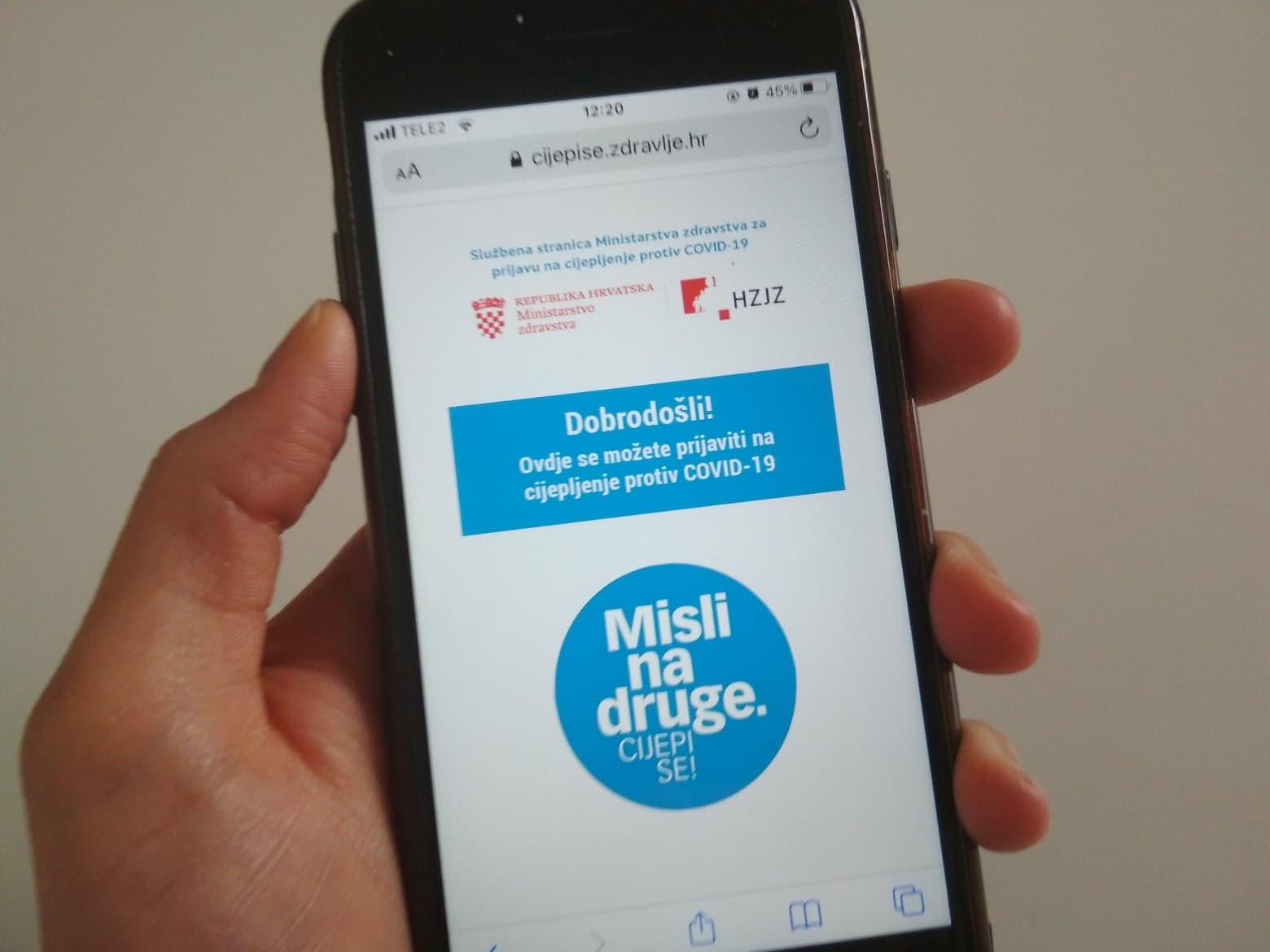

As more doses of COVID-19 vaccines finally arrive in Croatia, problems continue when it comes to registration, especially through the national online platform, CijepiSe [Get vaccinated].

“I expected the CijepiSe platform to work because the pandemic has lasted such a long time,“ Mia Biberovic, executive editor at the Croatian tech website Netokracija, told BIRN.

“I assumed the preparations were done early enough,“ she said, concluding that alas, this was not the case. As a consequence, she noted, a small number of people who applied online for a jab are being invited to get vaccinated.

For days, media have reported on problems with the platform, which cost 4.4 million kuna, or about 572,000 euros. On Friday, media reported that the data of the first 4,000 people who applied for vaccination via the platform during its test phase in February had been deleted.

The health ministry then denied reports about the deletion, and said the data relevant for making vaccination appointments had not connected in the case of 200 citizens who booked vaccinations during the test trial.

“The problem is, first, that the test version came when it [the system] was not functional yet. Second, [in the test phase] there were no remarks about the protection of users’ data, i.e. how the user data left there would be used,” Biberovic, who was also among those who applied during the test trial, noted.

“As far as I understood, the data was not deleted but could not be seen anywhere because it was incomplete … So they are not deleted, but again, they are not usable, which is even more bizarre,“ Biberovic added. “This is certainly a risk because citizens do not know how their data is being used.”

Vaccination appointments in Croatia can be ordered through the CijepiSe online platform, a call centre or via general practitioners, and all those who apply should be put on a single list. However, direct contact with a doctor has turned out to be the best way to get a vaccination appointment.

The ministry on Saturday said 198,274 citizens have been registered via the CijepiSe platform, of whom 45,416 have been vaccinated. But around 40,000 of these were not invited through the platform but by direct invitation of general practitioners.

Zvonimir Sostar, head of the Zagreb-based Andrija Stampar Teaching Institute of Public Health, stated on Saturday that the platform was not functioning in the capital, and that they would change the vaccination registration system, advising citizens to register via general practitioners.

Shortly after, the ministry promised that “everyone registered in the CijepiSe system will receive their vaccination appointment”.

“Maybe the platform is not functioning the way we wanted, but it functions well enough to cope with the challenges of vaccination. I read in the papers that the system of vaccination has collapsed. That’s not true! We are increasing the daily number of vaccinations,” Health Minister Vili Beros said on Sunday.

However, the Conflict of Interest Commission, an independent state body tasked with preventing conflicts of interest between private and public interests in the public sector, confirmed on Tuesday that it has opened a case against Beros. It comes after the media reported that the minister has ties to the company that designed the CijepiSe platform. The minister denies any wrongdoing.