Using Huawei components within 5G infrastructure is not a direct violation of European Union guidelines, since the EU toolbox on 5G – a common set of guidelines laid out by the bloc to limit 5G cybersecurity risks – did not explicitly ban any specific company but left it to member states to decide which providers were ‘high-risk’.

Authorities in Cyprus have not as yet identified any provider as ‘high-risk’.

The October 2020 memorandum of understanding that saw Cyprus sign up to the US Clean Network “does not imply in an implicit or explicit way that Cyprus will move away from Huawei”, said the man who signed it, Deputy Minister for Research, Innovation and Digital Policy Kyriacos Kokkinos.

“What it says is that we will collaborate with US agencies and authorities so that we ensure that the security standards are respected in the infrastructure we deploy,” Kokkinos told BIRN.

EU guidelines, however, do stress caution over suppliers “subject to interference from a non-EU country”, warning that a member state’s network could be vulnerable if there was a “strong link between the supplier and a government of a third country.”

Huawei’s state ties are considerable.

Zhengfei, the company’s founder, was a former Deputy Regimental Chief of the People’s Liberation Army; reports say that a considerable number of Huawei employees are believed to have worked for the military; and some Huawei employees have collaborated on research projects with military personnel.

But it was legislation passed in China in 2017 that really raised eyebrows.

Article 7 of China’s 2017 National Intelligence Law requires any organisation to support, provide assistance and cooperate in “national intelligence work”. Even before that, Article 22 of the 2014 Counter-Espionage Law required any “relevant organisations and individuals” to “truthfully provide” information during any “counter-espionage investigation”.

China’s “military-civil fusion” – which calls for private sector assistance in the country’s military objectives – was inscribed as a strategic priority in the Chinese Communist Party’s constitution in October 2017.

Some European countries have already balked.

In October, Swedish telecom regulator PTS banned Huawei from supplying 5G equipment to Swedish mobile firms due to security concerns raised by Sweden’s SAP security service, a decision upheld by a Swedish court in June this year.

Huawei has repeatedly denied posing a security threat, while China threatened “all necessary measures” in response to the Swedish ban. Beijing also told France and Germany not to “discriminate” against the company.

In the United Kingdom, a firm US ally, the government set a cap of 35 per cent limit on Huawei’s involvement in 5G RAN. It also excluded Huawei from safety-related and safety critical networks and sensitive locations such as nuclear sites and military bases.

In Cyprus, Kokkinos would not be drawn on whether Cyprus might set a similar cap.

“I don’t want to make a statement that might be misleading that this is not something that might happen in the future,” he said. “But at the moment we do not exclude any vendor.”

Critics of the Chinese government say the stakes could not be higher.

Given how much states and societies will come to depend on fifth generation technology, its security poses an unprecedented challenge, with any potential ‘hack’ snowballing into a threat to national security.

As a host to British military bases and US spy stations at the crossroads of Europe, Asia and the Middle East, Cyprus is no ‘island’ when it comes to geostrategic importance. Some experts say the threat posed by Huawei’s political and military ties and its data dominance in Cyprus cannot be ignored.

“One day Cyprus has to choose a side,” said Chen Yonglin, a former Chinese consular official in Sydney, Australia, whose work included monitoring Chinese dissidents until he defected in 2005. “One day China will take off its mask and Cyprus won’t be able to stand in the middle.”

“Cyprus needs to be careful about handing over its sovereignty to China,” he told BIRN.

John Strand, director and founder of telecommunications consultancy firm Strand Consult, concurred:

“The China we have today is a different China than we had five years ago,” he said. “China is a country which is very aggressive to countries which basically have an opinion, or have citizens who have an opinion about what is going on in China, Hong Kong or Tibet, and other places.”

“We have seen that China is not only threatening countries which go against them or criticise them, they also punish countries,” he told BIRN.

“If the Internet broke down 10 to 15 years ago, society could move on, it was not an issue. Nowadays, everything in our society is built on top of IT solutions which are connected to each other through the Internet of Things.

Cyprus embraces Chinese blockchain

Huawei, however, is not the only cause of potential concern when it comes to Cyprus.

Another is VeChain, a Chinese state-backed blockchain platform that in November 2018 entered into a national partnership with Cyprus to assist the island in the development and implementation of blockchain solutions across a range of private and public sectors.

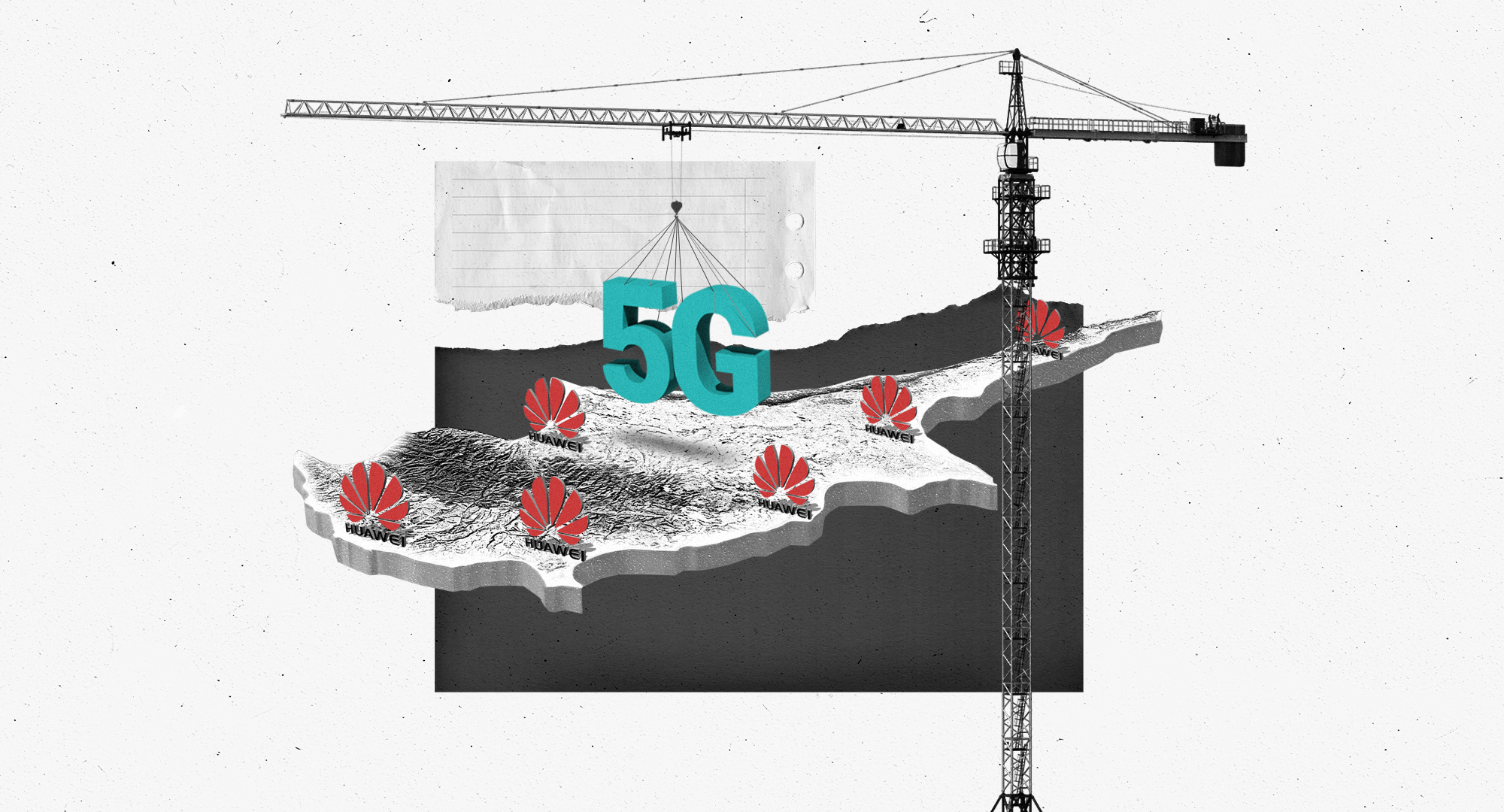

Illustration: BIRN/Igor Vujcic

Illustration: BIRN/Igor Vujcic Huawei (Nicosia)-the building in which Huawei’s main Cyprus offices reside. Photo: BIRN

Huawei (Nicosia)-the building in which Huawei’s main Cyprus offices reside. Photo: BIRN

Mediterranean Hospital of Cyprus (Limassol),one of two Cypriot hospitals to partner with VeChain store vaccination records on the VeChainThor blockchain. Photo: BIRN

Mediterranean Hospital of Cyprus (Limassol),one of two Cypriot hospitals to partner with VeChain store vaccination records on the VeChainThor blockchain. Photo: BIRN Passport control at the derelict former Nicosia International Airport in Nicosia, Cyprus. Photo: EPA/JAN RAKOCZY

Passport control at the derelict former Nicosia International Airport in Nicosia, Cyprus. Photo: EPA/JAN RAKOCZY