Balkan countries have experienced a general stagnation or deterioration in terms of media pluralism and media freedoms during 2020, shows a new study, “Media Pluralism Monitor 2021”, published by the Centre for Media Pluralism and Media Freedom at the European University Institute.

These trends can be observed through the four fundamental risk areas encompassed in the study: fundamental protection, market plurality, political independence and social inclusiveness.

Medium and high-risk factors for Balkan countries

In the area of fundamental protection, which among other things encompasses the protection of freedom of information, right to information and observing of journalistic standards, North Macedonia scores best out of all the Balkan countries in the study.

On a scale from 0 to 100 when scores between 0 and 33 per cent are marked as low risk factors, scores between 34 to 66 per cent mark medium risk, and scores between 67 and 100 per cent indicate high risk, only North Macedonia was marked as low risk, with a score of 32 per cent.

The rest of the countries were put in the medium risk group. Croatia scored 42 per cent, Montenegro 43 per cent, Serbia 45 per cent, Slovenia 48 per cent and Albania 59 per cent.

In the area of market plurality, which looked at issues like transparency of media ownership, news media concentration and owners’ influence over the editorial policies of the outlets, Montenegro was ranked best with 62 per cent, followed by North Macedonia with 64 per cent, both being ranked medium risk.

The rest of the countries were marked high risk. Serbia scored 69 per cent, Croatia 71 per cent, Slovenia 76 per cent while Albania ranked worst, with 89 per cent.

The third area concerns over political independence, which measures indicators such as editorial autonomy, state regulation and resources allocated to media and the independence of funding. All countries from the region in the survey, bar Slovenia, were marked as medium risk.

North Macedonia again scored best with 50 per cent, followed by Serbia on 57 per cent, Croatia with 61 per cent, Montenegro and Albania which both scored 64 per cent. Slovenia was marked as a country of high risk with a score of 73 per cent.

The fourth fundamental risk area in the report, social inclusiveness, encompasses indicators like access to media by minorities, as well as for local and regional communities, access to media for women, media literacy as well as protection against illegal or harmful speech.

In this risk area, North Macedonia again scored best with 58 per cent, followed by Croatia with 61 per cent, the only two countries marked with a medium risk factor.

Serbia scored 67 per cent, Slovenia 70 per cent, Albania 72 per cent and Montenegro scored worst, with 73 per cent.

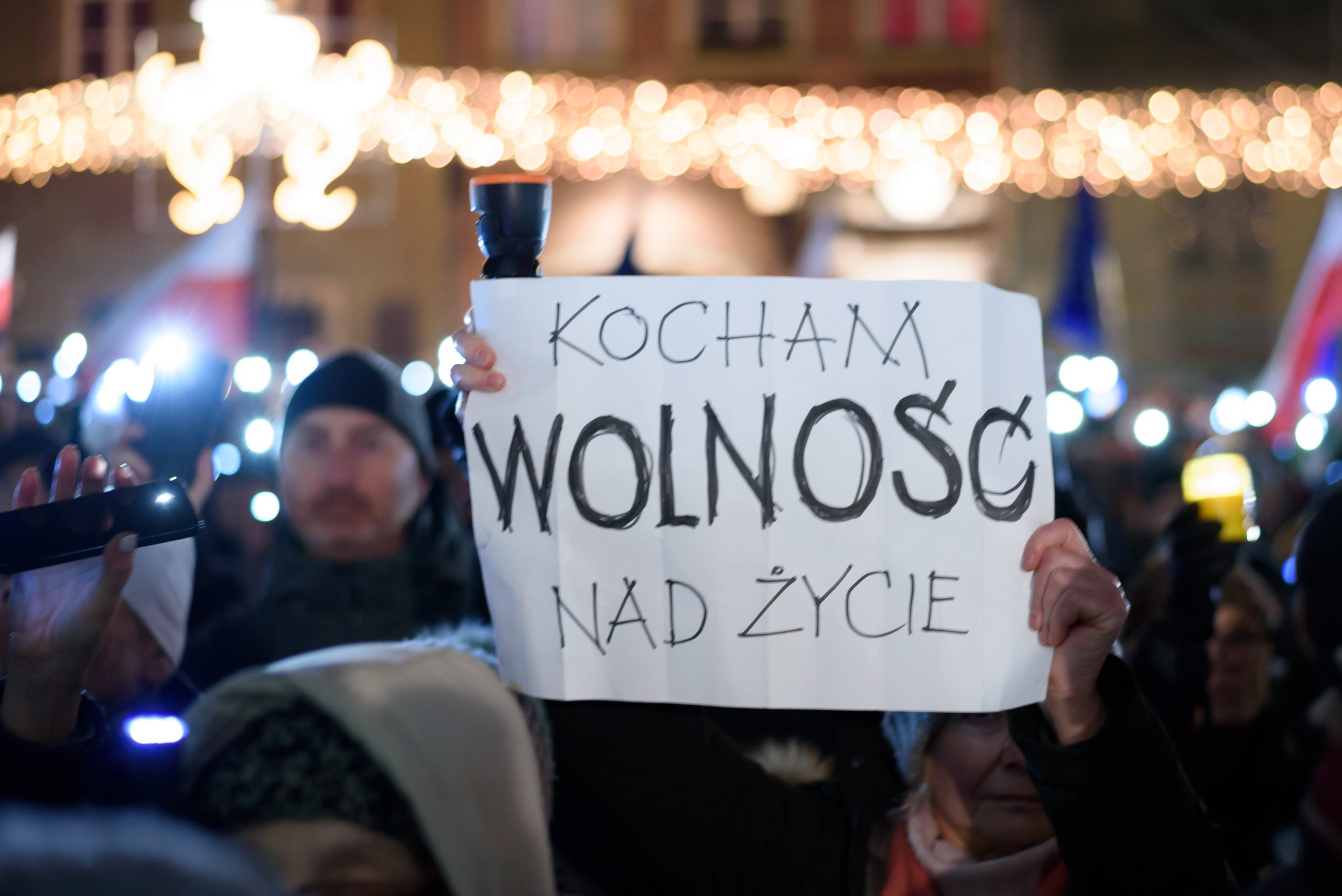

Illustration: Pixabay

General stagnation or decline

Starting with Slovenia, the report noted that all monitored areas showed a slight or significant deterioration compared to the findings of the Media Pluralism Monitor 2020.

“Unlike many other EU countries, Slovenia and its government did not enable or promote any financial, fiscal, or tax instrument, strategy, or other potential intervention aimed at strengthening media plurality or, for example, social inclusiveness” during the pandemic of 2020, the report noted.

For Croatia, another EU country, the report noted that the regulation of the media sector has been stagnant for years, which has resulted in the deterioration of media pluralism.

The report said that, “there is no overarching media strategy, or initiative, to tackle specifically local issues such as poor protection of the journalistic profession and standards. The country has seen a surge of SLAPPs and defamation charges aimed at journalists”, adding: “Political interference without considerations of public interests is seen in many appointment procedures: from the public service media to the main media regulator.”

On Albania, the report noted that the country is weakest in terms of market pluralism, where it “faces a high level of news media concentration in its audio visual media market, while the viability of most outlets – apart from a number of family owned conglomerates that control the lion share of revenues and audiences, is weak”.

In the area of fundamental protection, Albania should do more to increase professional and journalistic standards, the report said, in order to avoid the threat of government intervention to regulate online media content, as proposed by the current ruling Socialist Party.

As for Montenegro, the report said the country’s legal framework is suitable for the development of media pluralism, but more in a quantitative than in a qualitative sense.

While the process of establishing media, especially online, is extremely free, there is no effort to boost professional or ethical standards. In addition, efforts to create and implement rules for digital news media that limit political influence have generally been sporadic, insufficient, and ineffective, the report said.

“Existing legal solutions allow political power to control the public broadcaster and the other media at the national and local levels, the report further states, especially through their dependency on public financing” the report also noted.

The report also said that the establishment of the state-level Fund for Encouraging Media Pluralism and Diversity is an innovation that may yet prove its worth, provided that strong control over the distribution of resources is established.

When it comes to Serbia, the general conclusion is that while the country has a solid legal framework covering traditional media, full enforcement of this is missing.

Some highlighted points are political and state advertising in media, lack of transparent media ownership and the lack of protection for media workers and instances of attacks on journalists that remain unsanctioned.

“During the 2020 election campaign, the so-called functionary campaign turned out to be the weakest element in media regulation, so this issue should be arranged by the Law. The area of political advertising and reporting on spending on online platforms campaigns should be regulated by the Law as well. Political advertisement should be equally accessible to all political players, under the same conditions,” the report said.

Of the six countries from the region, North Macedonia had the highest overall score. The report notes that the situation in 2020 “significantly improved” compared to 2016, the last year of the former authoritarian PM Nikola Gruevski who was ousted in 2017.

The report notes that media freedoms are broader, journalists and their associations are no longer exposed to serious physical attacks and pressures, and the regulator is fairly independent and more efficient.

However, risks remain present: “The market is fragmented, most media are economically weak, and the working status of journalists is still unstable,” the report noted.

In general, for all countries, the report points out that for most of the countries’ populations, especially the young, online media have become their main source of information, and with this comes their increased exposure to disinformation and hate speech.

This creates a new challenge for all these countries’ regulatory policies, the report concludes.

The Media Pluralism Monitor 2021 was published as a research tool designed to identify potential risks to media pluralism in member states of the European Union and candidate countries.

The project, under a preparatory action of the European Parliament, was supported by a grant awarded by the European Commission to the Centre for Media Pluralism and Media Freedom at the European University Institute.