Serbian police clashed with thousands of angry citizens on Wednesday night, on the second day of protests against the official handling of the coronavirus crisis and the announced reimposition of restrictive measures, including a curfew on weekend. Besides the capital city of Belgrade, protests were held in other cities, including Novi Sad, Nis, Kragujevac and Smederevo.

In Belgrade, violent clashes with police lasted hours, with police using tear gas to disperse crowds. In Kragujevac, protesters smashed some of the windows of the police building.

Protesters in Novi Sad threw rocks and rubbish bins at the windows of the ruling Progressive Party facilities, at Radio Television of Vojvodina and at city hall, breaking some windows.

Miran Pogacar, one of the people who called for protests in Novi Sad, blamed pro-government infiltrators for the violence in Novi Sad. Pogacar was arrested some hours later and is still in custody.

In Belgrade, 19 policemen and 17 protesters were injured on Wednesday night, according to city hospital data.

Cameras caught numerous examples of the police using excessive force, with several attacks on journalists also reported.

Journalists from Nova.rs portal, Beta news agency, as well as from the Serbian public broadcaster RTS were all attacked while covering the protests on Wednesday night – the latter by the protesters.

Three journalists of Nova.rs said they were attacked by police, although they had identified themselves as journalists.

Marko Radonjic said he was hit by a police baton and threatened with arrest. Police hit another journalist, Milica Bozinovic while knocking her phone to the ground. Her colleague Natasa Latkovic’s journalists ID was thrown by the police, Nova.rs said.

Beta news agency said police injured their reporter, despite showing them a journalist’s ID. The journalist suffered cuts to his head and near his eye, and the police also returned to beat him while he was lying on the ground.

“They beat him with batons, even though he let them know that a journalist was on duty, even when he fell to the ground,” Beta said.

In Nis, protesters surrounded the journalist and the cameraman from Radio Television of Serbia, RTS, insulted them and grabbed their microphones and camera cables, while the cameramen was hit on the head with a bottle.

The violence stopped after journalists from Juzne vesti intervened and helped their colleagues escape the area. RTS has been widely criticized by protesters for not properly reporting the rallies.

The SafeJournalists network, which represents more than 8,200 media professionals in the Western Balkans, on Thursday condemned the violence against journalists and asked the authorities to guarantee their rights to work.

“In accordance with its mandate, the police must ensure a safe working environment for journalists and must determine who and why has violated their rights during the protest. It must determine whether the powers of the police have been exceeded and, if so, prosecute the responsible persons,” it said.

Interior Minister Nebojsa Stefanovic said on Wednesday night at a press conference that the police had acted with restraint while they were pelted with stones and torches and had reacted in self-defence.

“They started intervening when the violence became unbearable and when their lives were in danger,” Stefanovic said.

Tanja Fajon, president of the European Parliament’s Stabilization and Association Committee between Serbia and the EU, wrote on Twitter on Wednesday that the footage from Serbia looked brutal and that the safety and health of people should come in the first place.

“The use of force is unacceptable. Angry people accuse President Vucic of deliberately concealing the real health picture [with COVID-19] until the recent elections. Safety and health of people are in the first place. But not with repression,” Fajon wrote on Twitter. .

President Aleksandar Vucic on Wednesday blamed far-right organisations, anti-migrant extremists and fantasists who “believe the Earth is a flat plate” for the violence.

“These people were not talking about coronavirus – they were talking about some kind of betrayal, about migrants, the 5G network and the earth as a flat plate, and these people were not there for the first time, only their degree of aggression was higher,” Vucic said.

He added that one reason for the protest was to weaken the position of Serbia ahead of the continuation of the EU-aided dialogue with Kosovo.

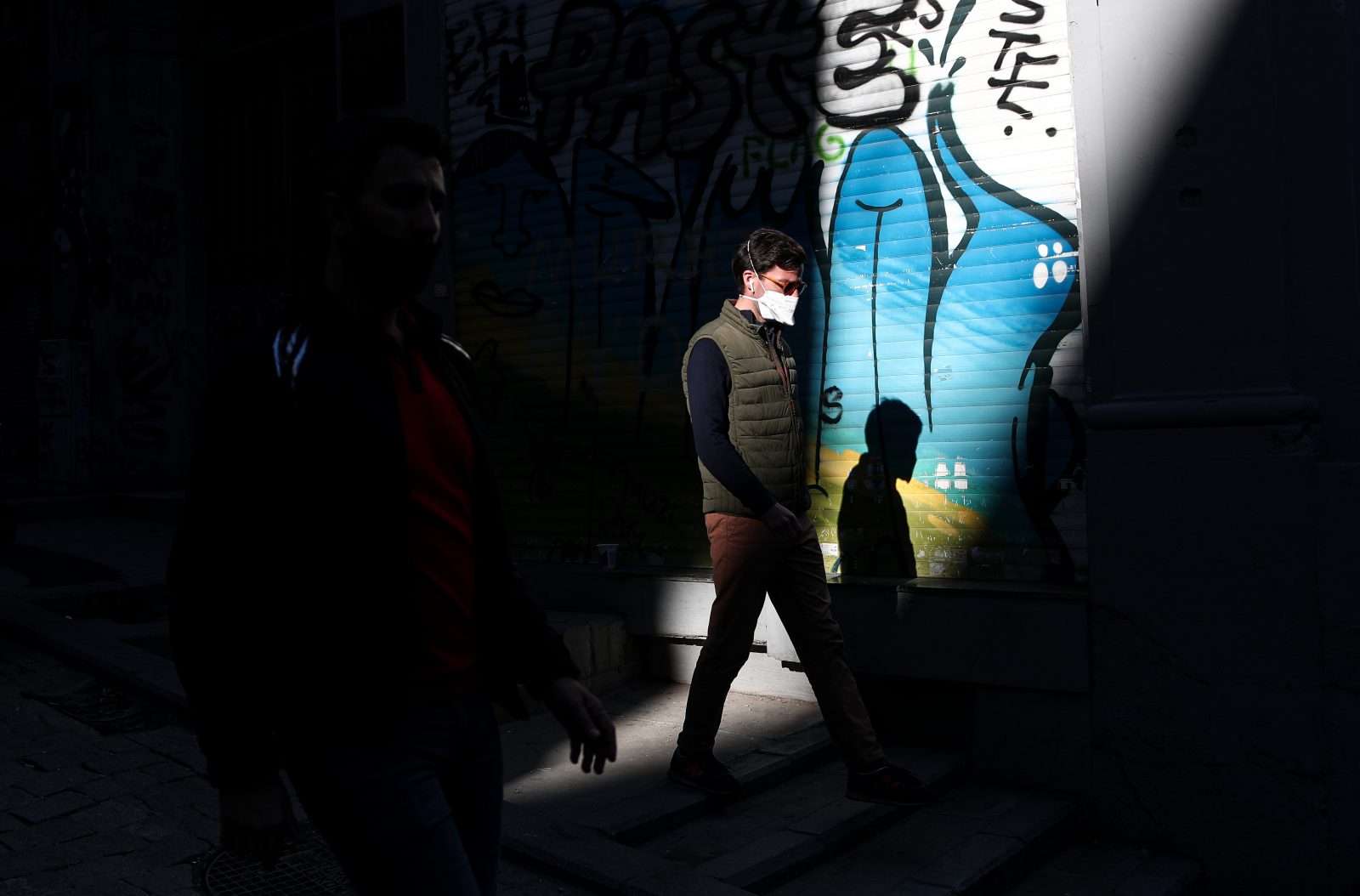

Violent protests erupted on Tuesday evening after Vucic announced that, due to the rise in COVID-19 cases, the capital might again be under a curfew this weekend.

During the now lifted state of emergency, Serbian citizens spent several whole weekends under curfews. Serbia was one of few countries in Europe to impose such tough measures.

Critics accused the President of manipulating health measures for his own political gains. He lifted heavy restrictions ahead of the elections on June 21.

In the run-up to the election, no restrictions were in place. During that time, political parties held rallies, the government allowed football games to take place in the presence of thousands of people, while the state Crisis Staff said situation with the coronavirus was no longer alamring.

The day after the elections, BIRN published an investigation that showed that more than twice as many infected patients had died in Serbia than the authorities announced, and hundreds more people had tested positive for the virus in than was admitted.

After the elections, when the numbers of deaths and infections again started to increase, many towns and cities in Serbia announced states of emergency linked to the pandemic.