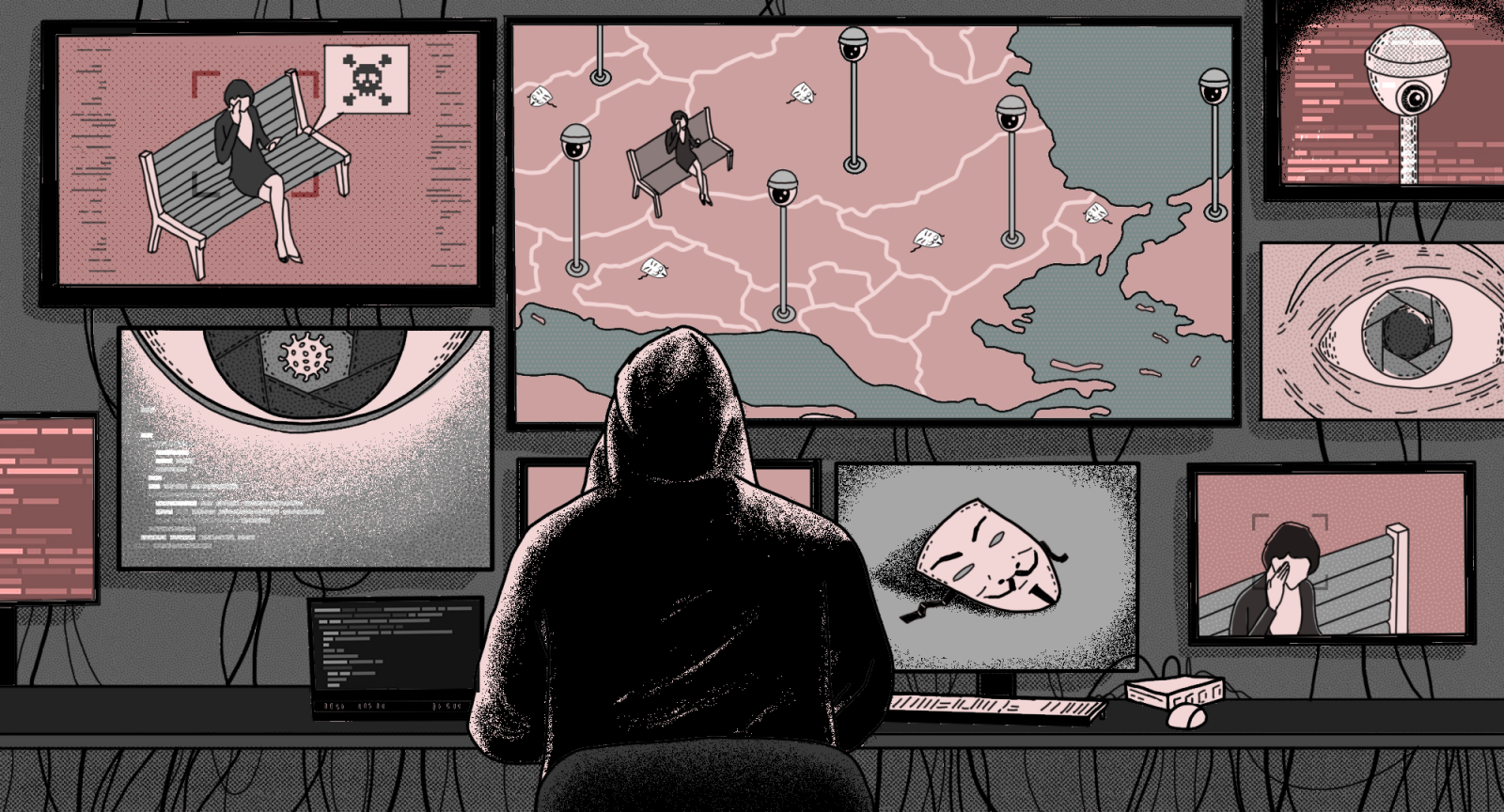

Digital rights violations have been rising across Southeastern Europe since the beginning of the COVID-19 pandemic with a similar pattern – pro-government trolls and media threatening freedom of expression and attacking journalists who report such violations.

“Working together is the only way to raise awareness of citizens’ digital rights and hold public officials accountable,” civil society representatives attending BIRN and Share Foundation’s online event on Thursday agreed.

The event took place after the release of BIRN and SHARE Foundation’s report, Digital Rights Falter amid Political and Social Unrest, published the same day.

“We need to build an alliance of coalitions to raise awareness on digital rights and the accountability of politicians,” said Blerjana Bino, from SCiDEV, an Albanian-based NGO, closely following this issue.

When it comes to prevention and the possibilities of improving digital competencies in order to reduce risks about personal data and security, speakers agreed that digital and informational literacy is important – but the blame should not be only put on users.

The responsibility of tech giants and relevant state institutions to investigate such cases must be kept in mind, not just regular cases but also those that are more complicated, the panel concluded.

Uros Misljenovic, from Partners Serbia, sees a major part of the problem in the lack of response from the authorities.

“We haven’t had one major case reaching an epilogue in court. Not a single criminal charge was brought by the public prosecutor either. Basically, the police and prosecutors are not interested in prosecuting these crimes,” he said. “So, if you violate these rights, you will face no consequences,” he concluded.

The report was presented and discussed at an online panel discussion with policymakers, journalists and civil society members around digital rights in Southeast Europe.

It was the first in a series of events as part of Platform B – a platform that aims to amplify the voices of strong and credible individuals and organisations in the region that promote the core values of democracy, such as civic engagement, independent institutions, transparency and rule of law.

Between August 2019 and December 2020, BIRN and the SHARE Foundation verified more than 800 violations of digital rights, including attempts to prevent valid freedom of speech (trolling of media and the public engaged in fair reporting and comment, for example) and at the other end of the scale, efforts to overwhelm users with false information and racist/discriminatory content – usually for financial or political gain.

The lack of awareness of digital rights violations within society has further undermined democracy, not only in times of crisis, the report reads, and identifiers common trends, such as:

- Democratic elections being undermined

- Public service websites being hacked

- Provocation and exploitation of social unrest

- Conspiracy theories and fake news

- Online hatred, leaving vulnerable people more isolated

- Tech shortcuts failing to solve complex societal problems.

The report, Digital Rights Falter amid Political and Social Unrest, can be downloaded here.