The report presents an overview of the main violations of digital rights in Bosnia and Herzegovina, Croatia, Hungary, Kosovo, Montenegro, North Macedonia, Romania and Serbia between January 31 and September 30, 2020, and makes a series of recommendations for authorities in order to curb such infringements during future social crises.

A first report, compiled by BIRN and which contained preliminary findings, showed a rise in digital rights violations in Central and Southeastern Europe during the pandemic, with over half of cases involving propaganda, disinformation or the publication of unverified information.

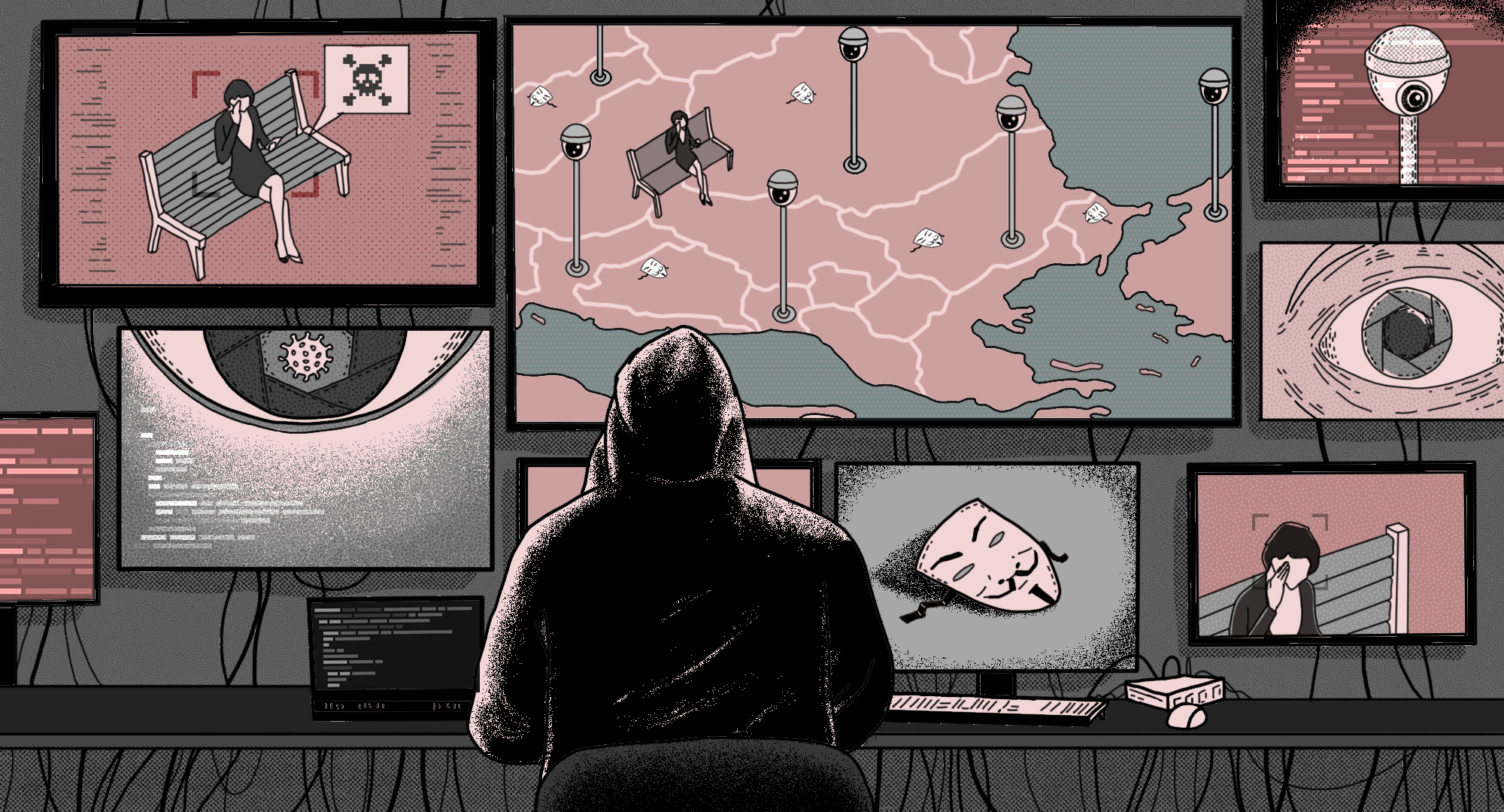

The global public health crisis triggered by the coronavirus exposed a new the failure of states around the world to provide a framework that would better balance the interests of safety and privacy. Instead, the report documents incidents of censorship, fake news, security breaches and concentration of information.

More than 200 pandemic-related violations tracked

At the onset of the pandemic, numerous violations of digital rights were observed – from violations of the privacy of persons in isolation to manipulation, dissemination of false information and Internet fraud.

BIRN and Share Foundation documented 221 violations in the context of COVID-19 during the eight-month monitoring period, the largest number coming during the initial peak of the pandemic in March and April – 67 and 79 respectively – before slowly declining.

The countries with the highest number of violations to date are Serbia, with 46, and Croatia, with 44.

The most common violation – accounting for roughly half of all cases – was manipulation in the digital environment caused by news sites that published unverified and inaccurate information, and by the circulating of incomplete and false data on social media.

This can be explained in large measure by the low level of media literacy in the countries of the region, where few people actually check the news and information provided to them, while the media themselves often publish unverified information.

The most common targets of digital rights violations were citizens and journalists. However, both of these groups were frequently also among the perpetrators.

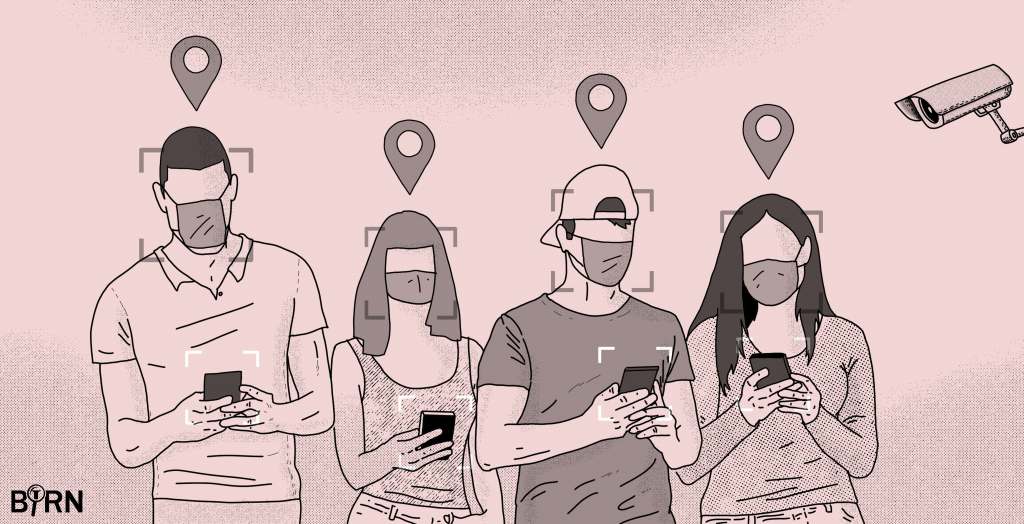

Contact tracing apps: Useful or not?

The debate about the use of contact-tracing apps as a method of combating the spread of COVID-19 was one of the most important discussions in Croatia and North Macedonia.

At the very beginning of the pandemic, the Croatian government led by the conservative Croatian Democratic Union, HDZ, proposed a change to the Electronic Communications Act under which, in extraordinary situations, the health minister would request from telecommunications companies the location data of users.

Similarly, Macedonian health authorities announced they were looking to use “all tools and means” to combat the virus, with North Macedonia among the first countries in the Western Balkans to launch a contact-tracing app on April 13.

Developed and donated to the Macedonian authorities by Skopje-based software company Nextsense, the StopKorona! app is based on Bluetooth distance measuring technology and stores data locally on users’ devices, while exchanging encrypted, anonymised data relevant to the infection spread for a limited period of 14 days. According to data privacy experts, the decentralised design guaranteed that data would be stored only on devices that run the app, unless they voluntarily submit that data to health authorities.

Croatia launched its own at the end of July, but by late August media reports said the Stop COVID-19 app had been downloaded by less than two per cent of mobile phone users in the country. The threshold for it to be effective is 60 per cent, the reports said.

Key worrying trends mapped

Bosnia and Herzegovina saw a number of problems with personal data protection, free access to information and disinformation. In terms of disinformation, people were exposed to a variety of false and sometimes outlandish claims, including conspiracy theories about the origin of the coronavirus, its spread by plane and various miracle cures.

Conspiracy theories, like those blaming the spread of the virus on 5G mobile networks, flourished online in Croatia too. One person in Croatia destroyed their Wifi equipment, believing it was 5G.

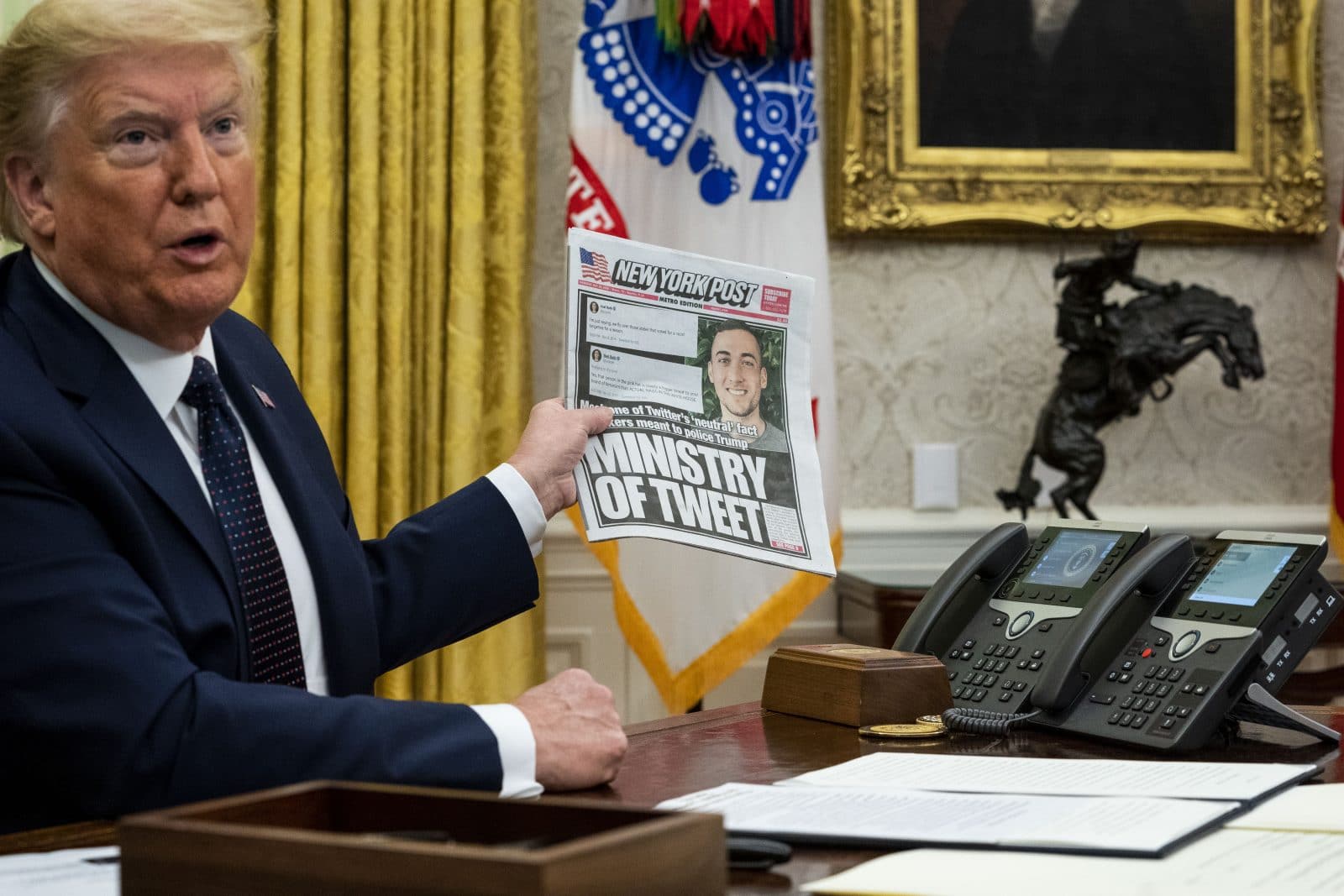

In Hungary, fake news about COVID-19 arrived even before the virus itself, said journalist Akos Keller Alant, who monitored the digital environment in Hungary.

Several clickbait fake news sites published articles about COVID-19 victims a month before Hungary’s first confirmed case. The Anti-Cybercrime Unit of the Hungarian police arrested several people for spreading fake news, starting in early February when police raided the operators of a network of fake news sites.

In Kosovo, online media emerged as the biggest violators of digital rights by publishing unverified and false information as well as personal health information. Personal data rights were also violated by state institutions and public figures.

In Montenegro, the most worrying digital rights violations concerned privacy and personal data protection of those infected with the coronavirus or those forced to self-isolate.

The early days of the pandemic, when Montenegro was among the few countries that could claim to have kept a lid on the virus, was a rare moment of social and political consensus in the country about how to respond, said Tamara Milas of the Centre for Civic Education in Montenegro, an NGO.

The situation changed, however, when the government was accused of the gross violation of the right to privacy and the right to the protection of personal data.

Like its Western Balkan peers, North Macedonia was flooded with unverified information and claims shared online with regards the pandemic. Some of the most concerning cases included false claims about infected persons, causing a stir on social media.

In Romania, the government used state-of-emergency powers to shut down websites – including news and opinion sites – accused of spreading what authorities deemed fake news about the pandemic, according to BIRN correspondent Marcel Gascon, who monitors digital rights violations in Romania.

In Serbia, a prominent case concerned a breach of security in the country’s central COVID-19 database. For eight days, the login credentials for the database, Information System COVID-19, were publicly available on the website of a public health body.

In another incident, the initials, age, place-of-work and personal address of a person infected with the virus were posted on the official webpage of the municipality of Sid in western Serbia as well as on the town’s social media accounts.

In the report, BIRN and Share Foundation conclude that technology, especially in a time of crisis, should not be seen as the solution to complex issues, be that protection of health or upholding public order and safety. Rather, technology should be used to the benefit of citizens and in the interest of their rights and freedoms.

When intrusive technologies and regulations are put in place, it is hard to take a step back, particularly in societies with weak democratic institutions, the report states. Under such circumstances, the measures applied in one crisis for the protection of public health may one day be repurposed and used against other “social plagues”, ultimately leading to reduced human rights standards.

To read the full report click here. For individual cases, check our regional database, developed together with the SHARE Foundation.