In October 2015, two years after a banking crisis left Cyprus in desperate need of new financing, President Nicos Anastasiades visited China on a charm offensive, touting the Mediterranean island’s low tax rates, its European Union membership and its readiness to take part in China’s Belt and Road Initiative, BRI.

The floodgates opened, but there was nothing sporadic about the Chinese outlay.

Today, money from Chinese state-owned or state-linked corporations has penetrated the core of just about every key Cypriot sector, from real estate to natural resources, transport to aviation, all in the name of a transcontinental infrastructure project linking countries along the route of the old Silk Road.

Thanks in part to the BRI, China is set to surpass the United States as the world’s leading economy by 2028 and become the standout superpower heading into the ‘Fourth Industrial Revolution.’

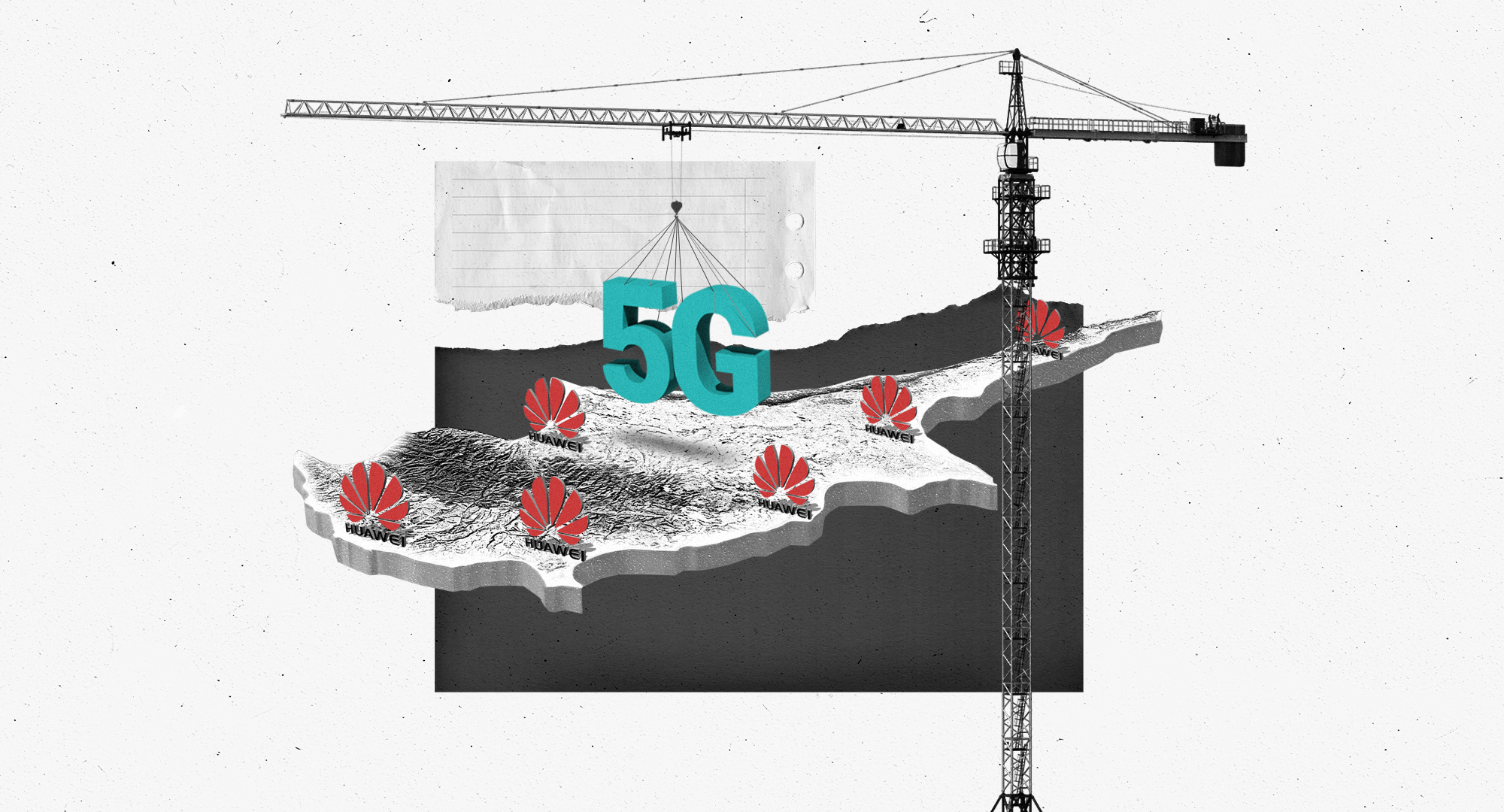

A key component of the BRI is the Digital Silk Road, DSR, through which the Chinese Communist Party seeks to develop and export key technological infrastructure – including 5G – to participating states, boosting the importance and presence of Chinese tech companies around the world and, to a degree, replicating its digital authoritarian model.

Chinese investments in Cyprus. Illustration: BIRN/Igor Vujcic

In Cyprus, according to BIRN’s findings, China now dominates the 5G networks and the island’s wider tech ecosystem, creating a key Chinese outpost inside the EU with potentially far-reaching consequences for data security and the independence of Cypriot – and by extension EU – foreign policy.

It is a state of affairs that contradicts US and EU recommendations and the island’s own claims to be pursuing a multi-vendor strategy.

5G underpins power grids, transportation and water supplies, and, in the future, will enable military tools including artificial intelligence, said Carisa Nietsche, associate fellow for the Transatlantic Security Program at the Washington-based Centre for a New American Security.

“In extreme cases, analysts suspect China could pull the plug on the network, gather intelligence from data pulsing through the networks or cut off a 5G-enabled energy grid,” Nietsche told BIRN.

Chinese investment in Cyprus

In 2015, China’s largest private copper smelter, Yanggu Xiangguang Copper, bought a 22 per cent stake in Cyprus-registered copper mining company Atalaya Mining Plc for 96.2 million euros.

In November 2019, a consortium led by state-owned China Petroleum Pipeline Engineering signed a 290 million-euro deal with the Cypriot natural gas infrastructure company ETYFA to build a liquefied natural gas terminal for electricity generation. Among the four firms in the consortium is state-owned Hudong-Zhonghua Shipbuilding, the top warship producer for the Chinese navy.

Before it pulled out in 2019, state-owned Aviation Industry Corp. of China, AVIC, was the largest shareholder in Cypriot airline Cobalt.

JimChang Global Group has invested 100 million euros in a five-star hotel and housing development near Ayia Napa via a joint venture announced in 2016 with Cyprus property group Giovani. The residential part was completed last year.

Macau-based Melco is investing $677 million in the City of Dreams Mediterranean, an ‘integrated casino resort’ in Limassol, Cyprus. It is expected to open in 2022.

Building 5G on Chinese foundations

Illustration: BIRN/Igor Vujcic

Illustration: BIRN/Igor Vujcic

On his 2015 visit to China, Anastasiades, who was re-elected in 2018, visited the Shanghai research centre of Huawei, the world’s largest manufacturer of telecommunications equipment.

Huawei plays a key role in driving global industry standards in Beijing’s favour through the filing of patents that make the industry more likely to adopt Chinese proposals as global standards.

In terms of 5G standard essential patents, Huawei has the largest portfolio worldwide. The company claims to hold more commercial 5G contracts than any other telecom manufacturer in the world – 91. Forty-seven of these are in Europe.

At the research centre, Anastasiades lauded Huawei’s “important contributions to communications network construction in Cyprus” and called for “deeper ties”.

Huawei’s dominance, however, has unsettled the United States and others, which say the company’s equipment could be used by Beijing for spying, something Huawei has vigorously disputed.

In a rare interview with foreign media in 2019, Huawei founder and CEO Ren Zhengfei said: “I love my country. I support the Communist Party. But I will not do anything to harm the world.” He said that Beijing had never asked him or Huawei to share “improper information” about its partners and that he would “never harm the interest” of his customers.

Unconvinced, in October 2020 then US undersecretary of state for economic growth, energy and the environment, Keith Krach, visited Nicosia and, with the 5G licence application process underway in Cyprus, incorporated the island into the US ‘Clean Network’ on 5G, an initiative launched under former President Donald Trump to build a global alliance excluding technology that Washington says can be manipulated by the Chinese Communist Party.

The Americans are concerned, in part, by the proximity of Chinese-dominated 5G networks to military bases. But while on paper the Cypriots may have sided with the Americans, in practice Huawei is still very much in play.

Huawei (Nicosia)-the building in which Huawei’s main Cyprus offices reside. Photo: BIRN

Huawei (Nicosia)-the building in which Huawei’s main Cyprus offices reside. Photo: BIRN

The company entered the local market in 2009, taking a lead role in the upgrade of the island’s information and communications technology and the 2/3/4G infrastructure of its four telecommunications companies, CyTA, Epic, Cablenet and Primetel.

Since Cyprus uses the so-called Non-Standalone, or NSA, mode for 5G – effectively building on top of its existing 4G infrastructure – and with Huawei providing the components for 100 per cent of the telecom companies’ 4G Radio Access Network, RAN – the Chinese giant looked perfectly placed last year to take the lead in the 5G rollout as well.

The RAN is comprised of various facilities such as cell towers and masts that connect users and devices to the Core Network, which in turn encompasses all 5G data exchanges such as authentication, security, session management and traffic aggregation across devices.

In December 2020, the two biggest 5G contracts were awarded to CyTA and Epic.

But both companies, sources say, are overwhelmingly dependent on Huawei for their Core Network and their RAN infrastructure.

Semi-governmental CyTA launched its 5G Network in January 2021, catering to 70 per cent of the population on launch and aiming for 98 per cent coverage by the start of 2022.

A senior CyTA manager told BIRN that 80 per cent of the company’s Core Network and 100 per cent of its RAN is covered by Huawei infrastructure. The remaining 20 per cent of its Core Network is provided by Swedish Ericsson.

“CyTA is a governmental company and comes up with tenders for the equipment, and Huawei has been a long-term provider of infrastructure and support and offers the best prices,” said the senior manager, who asked not to be named since he was not authorised to speak to media.

Asked about the makeup of its Core Network and RAN infrastructure, CyTA told BIRN: “We inform you that any information regarding the CyTA network is a trade secret and any disclosure of it is contrary to the commercial interests of CyTA and its partners (article 34 (2) Law 184 (I) / 2017).”

Huawei also accounts for 90 per cent of Epic’s Core Network infrastructure and 100 per cent of the RAN, said a senior manager at Epic, who also spoke on condition of anonymity.

Epic’s collaboration with Huawei dates to 2009, when the company, then named MTN, sealed a 20 million-euro contract with the Chinese firm to upgrade its network.

Now owned by Monaco Telecom, Epic went on to develop Cyprus’s first 4G LTE network, leveraging Huawei’s RAN solution, on which another Cypriot telecommunications firm, Primetel, also entered into an access-sharing agreement. In February 2019, shortly before its rebranding as Epic, MTN signed a deal with Huawei for the development of its 5G network.

An Epic spokesperson did not respond to repeated requests for comment.

Nietsche, of the Centre for a New American Security, told BIRN: “For 5G to deliver on its promises of faster speeds, it requires an immense amount of data to travel through the network. And that data is pushed closer and closer to the end user, or the edge of the network.”

“In Europe, some governments have distinguished between implementation of Huawei in the Core Network and the Radio Access Network, or edge of the network. These governments argue that you can essentially create a firewall between the core and edge of the network.”

“However, we should not make such a distinction. As 5G networks develop, more and more data is pushed toward the edge of the network, and it becomes harder to distinguish between the core and edge of the network.”

Chinese ‘fusion’

Huawei section of the Gulf Information Technology Exhibition (GITEX) Global 2021. Photo: EPA-EFE/ALI HAIDER

Using Huawei components within 5G infrastructure is not a direct violation of European Union guidelines, since the EU toolbox on 5G – a common set of guidelines laid out by the bloc to limit 5G cybersecurity risks – did not explicitly ban any specific company but left it to member states to decide which providers were ‘high-risk’.

Authorities in Cyprus have not as yet identified any provider as ‘high-risk’.

The October 2020 memorandum of understanding that saw Cyprus sign up to the US Clean Network “does not imply in an implicit or explicit way that Cyprus will move away from Huawei”, said the man who signed it, Deputy Minister for Research, Innovation and Digital Policy Kyriacos Kokkinos.

“What it says is that we will collaborate with US agencies and authorities so that we ensure that the security standards are respected in the infrastructure we deploy,” Kokkinos told BIRN.

EU guidelines, however, do stress caution over suppliers “subject to interference from a non-EU country”, warning that a member state’s network could be vulnerable if there was a “strong link between the supplier and a government of a third country.”

Huawei’s state ties are considerable.

Zhengfei, the company’s founder, was a former Deputy Regimental Chief of the People’s Liberation Army; reports say that a considerable number of Huawei employees are believed to have worked for the military; and some Huawei employees have collaborated on research projects with military personnel.

But it was legislation passed in China in 2017 that really raised eyebrows.

Article 7 of China’s 2017 National Intelligence Law requires any organisation to support, provide assistance and cooperate in “national intelligence work”. Even before that, Article 22 of the 2014 Counter-Espionage Law required any “relevant organisations and individuals” to “truthfully provide” information during any “counter-espionage investigation”.

China’s “military-civil fusion” – which calls for private sector assistance in the country’s military objectives – was inscribed as a strategic priority in the Chinese Communist Party’s constitution in October 2017.

Some European countries have already balked.

In October, Swedish telecom regulator PTS banned Huawei from supplying 5G equipment to Swedish mobile firms due to security concerns raised by Sweden’s SAP security service, a decision upheld by a Swedish court in June this year.

Huawei has repeatedly denied posing a security threat, while China threatened “all necessary measures” in response to the Swedish ban. Beijing also told France and Germany not to “discriminate” against the company.

In the United Kingdom, a firm US ally, the government set a cap of 35 per cent limit on Huawei’s involvement in 5G RAN. It also excluded Huawei from safety-related and safety critical networks and sensitive locations such as nuclear sites and military bases.

In Cyprus, Kokkinos would not be drawn on whether Cyprus might set a similar cap.

“I don’t want to make a statement that might be misleading that this is not something that might happen in the future,” he said. “But at the moment we do not exclude any vendor.”

Critics of the Chinese government say the stakes could not be higher.

Given how much states and societies will come to depend on fifth generation technology, its security poses an unprecedented challenge, with any potential ‘hack’ snowballing into a threat to national security.

As a host to British military bases and US spy stations at the crossroads of Europe, Asia and the Middle East, Cyprus is no ‘island’ when it comes to geostrategic importance. Some experts say the threat posed by Huawei’s political and military ties and its data dominance in Cyprus cannot be ignored.

“One day Cyprus has to choose a side,” said Chen Yonglin, a former Chinese consular official in Sydney, Australia, whose work included monitoring Chinese dissidents until he defected in 2005. “One day China will take off its mask and Cyprus won’t be able to stand in the middle.”

“Cyprus needs to be careful about handing over its sovereignty to China,” he told BIRN.

John Strand, director and founder of telecommunications consultancy firm Strand Consult, concurred:

“The China we have today is a different China than we had five years ago,” he said. “China is a country which is very aggressive to countries which basically have an opinion, or have citizens who have an opinion about what is going on in China, Hong Kong or Tibet, and other places.”

“We have seen that China is not only threatening countries which go against them or criticise them, they also punish countries,” he told BIRN.

“If the Internet broke down 10 to 15 years ago, society could move on, it was not an issue. Nowadays, everything in our society is built on top of IT solutions which are connected to each other through the Internet of Things.

Cyprus embraces Chinese blockchain

Huawei, however, is not the only cause of potential concern when it comes to Cyprus.

Another is VeChain, a Chinese state-backed blockchain platform that in November 2018 entered into a national partnership with Cyprus to assist the island in the development and implementation of blockchain solutions across a range of private and public sectors.

Mediterranean Hospital of Cyprus (Limassol),one of two Cypriot hospitals to partner with VeChain store vaccination records on the VeChainThor blockchain. Photo: BIRN

Mediterranean Hospital of Cyprus (Limassol),one of two Cypriot hospitals to partner with VeChain store vaccination records on the VeChainThor blockchain. Photo: BIRN

It is the only such state partnership VeChain has outside of China.

The platform, launched in 2015, is a favourite of the Chinese Communist Party, which has entrusted it with contracts in, among other areas, agriculture and telecoms.

In July 2018, after thousands of children were given faulty vaccines, the Chinese government called on VeChain to create a nationwide vaccine tracking solution with health data stored on the blockchain.

When VeChain presented its solution at the China International Import Expo in November 2018, President Xi Jinping was in attendance. Xi has declared blockchain a national priority, with VeChain a co-founder of the Belt and Road Initiative Blockchain Alliance that aims to develop blockchain along the route of the BRI.

In Cyprus, VeChain developed the E-HCert App, which records COVID-19 PCR and antibody test results on the VeChain Thor Blockchain and is being expanded to serve as a wallet for all medical records of Cypriot citizens and as a vaccination certificate.

The ‘V-Pass’, a vaccination certificate sealed in the VeChain Thor, is also in the pipeline for the general public.

Two of the island’s biggest private hospitals have also struck agreements with VeChain for it to host their medical records on its blockchain.

Christiana Aristidou, co-founder and vice-chair of the Cyprus Blockchain Association, said that all necessary measures had been put in place “to maintain the safety of health data.”

“Blockchain is very secure and VeChain intends to take the lead in this sector in Cyprus,” Aristidou told BIRN.

Asked about any risks to data security, the Cypriot Health Ministry replied: “The Ministry of Health does not use blockchain technology in public hospitals.”

Golden passports and a city of dreams

But while some experts voice deep concern over the extent of China’s data presence in Cyprus, domestic scrutiny appears lacking. One reason may by the stakes involved for a number of influential political and legal figures.

In August 2020, an undercover report by Al Jazeera exposed a scam at the heart of a Cypriot policy to provide citizenship to foreign nationals who invest two million euros in the island’s economy.

According to the report, a number of high-level Cypriot officials had abused the scheme to secure passports for several thousand foreigners who did not meet the legal requirements.

Passport control at the derelict former Nicosia International Airport in Nicosia, Cyprus. Photo: EPA/JAN RAKOCZY

Passport control at the derelict former Nicosia International Airport in Nicosia, Cyprus. Photo: EPA/JAN RAKOCZY

An official investigation, published in June this year, said that 97 per cent of the 6,546 ‘golden’ passports issued between 2007 and August 2020 had been issued since Anastasiades took power in 2013.

More than half, or 3,609, were for family members of investors and executives of companies and who were granted citizenship without actually meeting the legal criteria.

Between 2017 and 2019, the Al Jazeera report found that 482 wealthy Chinese nationals applied for passports via the scheme, more than any other nationality bar Russian. They include several members of the Chinese People’s Political Consultative Conference, an advisory body to the Communist Party.

The chief protagonist in the Al Jazeera exposé was Dimitris Syllouris, who as speaker of the parliament at the time was the country’s second highest-ranking official after the president.

Syllouris was caught helping to fast-track a Cypriot passport for a fictitious Chinese businessman despite being told the applicant had a criminal record and was therefore barred from a ‘golden’ passport under the rules of the scheme.

Syllouris, who resigned over the scandal, had been a key player in a number of deals between Nicosia and Beijing, including in the tech sector.

Property developer and MP Christakis Giovanis, whose company partnered in 2016 with Chinese group JimChang Global on a 100 million-euro hotel and luxury housing development, also resigned his public post over the scam.

Invest Cyprus, the government agency tasked with attracting foreign investment and which signed the 2018 MoU with VeChain, plays a central role in bringing Chinese money into the country.

When Invest Cyprus facilitated the arrival in 2018 of Macau-based conglomerate Melco for the development of a casino mega resort worth $667 million in Limassol, the agency’s CEO, George Campanellas, became a member of the management team overseeing the project.

Melco CEO Lawrence Ho is a member of the National Committee of the Chinese People’s Political Consultative Conference, CPPCC, an advisory body to China’s central government.

Melco is also linked to the Cypriot telecom company Cablenet via the latter’s owner, Cyprus-based CNS Group, which is the parent company of The Cyprus Phassouri (Zakaki) Limited, Melco’s partner in the Integrated Casino Resorts Cyprus Consortium behind the Limassol casino development, City of Dreams Mediterranean. The resort is expected to open in 2022.

In 2019, Melco’s Ho attended the 2nd Belt and Road Forum for International Cooperation in Beijing with Melis Shiacolas, the managing director of CNS Group and a relative of Cablenet non-executive chairman and 37 per cent owner, Nicos Shiacolas.

The Invest Cyprus board also includes Pantelis Leptos, a prominent property developer whose law firm, Leptos Group, handled the paperwork for 169 applications to the golden passport scheme between 2013 and 2019, according to interior ministry data reported by Cypriot media group Dialogos. The company also has an office in China.

A senior official at Invest Cyprus initially agreed to be interviewed for this story but then said he needed to seek authorisation to speak to the media. He subsequently did not respond to repeated efforts to arrange a meeting.

In Paphos, on the southwest coast of Cyprus, the head of the local Chamber of Commerce and Industry, Andreas Demetriades, signed a memorandum of cooperation in 2017 with the Hi Tech District and Chamber of Commerce of the eastern Chinese city of Changzhou, near Shanghai, for the development of a pharmaceutical tech park in Paphos, with tech parks – industrial zones specialising in science and technology – high on the agenda of Invest Cyprus and the government.

Demetriades’ law firm, Andreas Demetriades LLC, handled 272 golden passport applications between 2013 and 2019, more than any other firm.

Stelios Orphanides, an investigative journalist with the Organised Crime and Corruption Reporting Project, OCCRP, said China could come to dominate the telecommunications sector “because there is the lowest level of scrutiny in terms of risk management.”

“Cyprus doesn’t have the will to carry out thorough checks,” he told BIRN, “because those who manage the system – both the old elites and new elites, lawyers, accountants and so on – have learned to do just one thing, which is to prostitute the sovereignty of Cyprus in exchange for personal benefits.”

Viktor Orban (C) with Slovenia’s current Prime Minister and leader of the Slovenian Democratic Party, SDS, Janez Jansa (R), and SDS MEP, Milan Zver (R), attending a SDS campaign event in Celje, Slovenia, in May 2018. Photo: EPA

Viktor Orban (C) with Slovenia’s current Prime Minister and leader of the Slovenian Democratic Party, SDS, Janez Jansa (R), and SDS MEP, Milan Zver (R), attending a SDS campaign event in Celje, Slovenia, in May 2018. Photo: EPA