Even in the best of times, it was difficult for Mamatjan Juma to maintain professional distance from his work. A former art teacher from the Uighur province of Xinjiang in China, he came to the US in 2003 and has worked as a journalist for Radio Free Asia’s Uighur service for 12 years. But in recent years, his family back in Xinjiang has been caught up in China’s mass detention of the Muslim minority population.

“When your relatives are detained and your colleagues are in trouble, it’s very hard to stay neutral,” Juma said, speaking at the 11th Global Investigative Journalism Conference in Hamburg. “We’re not an activist organization but it is a mission for us. We keep our emotions in check, then we cry at home.”

Today, Juma is deputy director of the US government-funded network’s Uighur service. His small team of Uighur exiles first broke the story of the mass internment camps in the western region of China in 2017. Since then, their reporting on the scale and conditions of the camps has won acclaim and provided a vital information lifeline in the Uighur language.

“We have been ignored for many years, but we’re gaining credibility, for example because we’re being cautious with our figures on the number of people in the concentration camps,” Juma said.

Reporting from exile is a tightrope walk of ethical quandaries and practical obstacles. Exiled journalists often have the language skills and local knowledge to provide crucial reporting on areas where few independent journalists have direct access, like Xinjiang. Yet they must also contend with the hostility of the governments that they fled.

While exiled reporters may now be practicing journalism from a place of relative safety, repressive governments can still interfere with their ability to report stories, reach audiences, and make a living.

Developing Sources

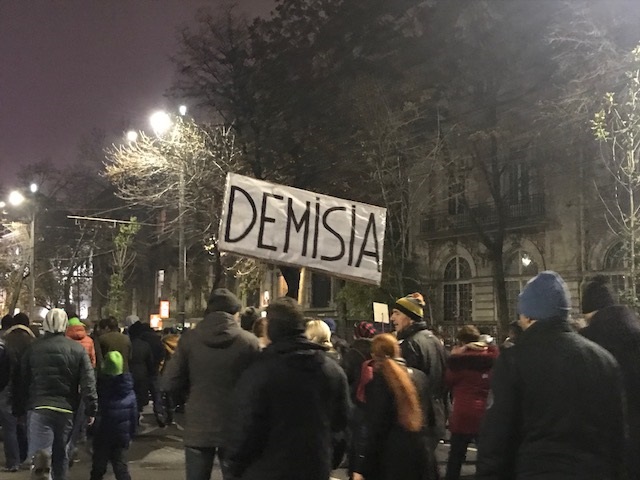

Ines Gakiza was working at the popular independent radio station Radio Publique Africaine when protests broke out in Burundi in 2015. Amid a violent government crackdown, the station was burned to the ground, and Gakiza fled to neighboring Rwanda. From there, she and other exiled colleagues continue broadcasting news about Burundi.

The biggest challenge of reporting from exile, Gakiza said, is to develop new sources inside the country, especially finding people from a variety of areas and walks of life. “Some people feel afraid to talk to people in exile, even if we don’t give their real names,” she said. “They might be seen as a collaborator.”

But the station is slowly gaining the trust of Burundians, despite its reporters’ exile. “People initially thought we wanted to use the radio for revenge, but four years later they see this is not our mission,” Gakiza said. “We want to tell Burundians and the world what is happening in our country.”

While Burundian officials usually hang up on the radio journalists whey they call for an official response, they often end up responding indirectly, by giving quotes to media inside the country, which Radio Publique Africaine can then use in their reporting.

And Gakiza and the other exiled journalists have been able to develop critical whistleblower sources inside the government. Some of these people joined the government or ruling party out of fear, and now they do not know how to leave, Gakiza said.

“We have some sources now we would never have dreamed of having before,” said Venezuelan investigative journalist Ewald Scharfenberg. He fled his country in January 2018 with colleagues from investigative news site Armando.info after being sued for criminal defamation over their corruption reporting. The former El Pais correspondent ended up in Colombia after Bogota-based magazine Semana invited the team to work out of its newsroom.

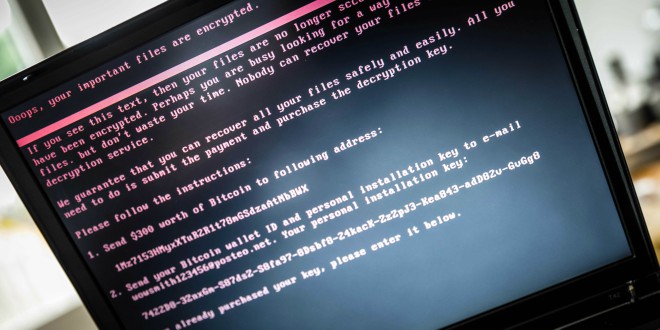

“We have sources in Venezuela who trust us with leaks because we are in Bogota — they are secure that we are not under certain pressures,” Scharfenberg said. This makes information security critical; the Armando.info team has received training on using secure communications in order to protect sensitive sources.

Reaching Audiences

When its journalists first left Burundi, Radio Publique Africaine was able to continue broadcasting in the country via the eastern Democratic Republic of Congo. But Burundian authorities soon demanded that the DRC shut down the frequency.

Today, they broadcast online only, using multiple channels like YouTube, SoundCloud, and WhatsApp in order to maximize their reach. They received some grant funding to get 10 computers and a small studio, but still struggle to keep afloat.

Armando.info is intermittently blocked in Venezuela, but most of its traffic still comes from inside the country. Raising funds from readers is difficult: Venezuela’s currency has collapsed amid an economic and political crisis. So the news site also turned to grant funding, even though they knew some of its readers might have reservations about US donors.

“Our idea was if we made [our funders] clear and transparent, then the reader can decide for themselves,” Scharfenberg said.

By contrast, Can Dündar, the former editor-in-chief of Turkish newspaper Cumhuriyet, relies on crowdfunding. In 2016, after being charged with treason and surviving an assassination attempt, Dündar fled to Germany. In 2017, he founded Özgürüz, an online magazine covering Turkey in German and Turkish, in collaboration with German investigative nonprofit Correctiv.

Finding funders was a major challenge. “You can’t ask Turks [to fund your journalism] as they’re afraid,” Dündar said. “You can’t ask Germans, as then you’re seen as a foreign agent.” Özgürüz now has around 500 individual donors, who mostly make small contributions to the news site. “It’s not big money but it’s like a solidarity campaign,” Dündar said.

Multiple Jurisdictions

When Galina Timchenko was fired as editor of the independent Russian site Lenta.ru in 2014, many of her colleagues followed her to Latvia, where she set up a new site called Meduza. Investigations editor Alexey Kovalev recently joined the team after leaving Russian state news agency RIA Novosti.

Meduza was funded by seed grants but also offers B2B (business-to-business) services, like an annual editors’ bootcamp. Around one-third of the staff — mainly reporters — are based in Russia. They don’t have an office there, as they fear it would be targeted. Meduza’s headquarters — and the majority of its staff — are based in the Latvian capital of Riga.

Besides the protection it offers to the journalists, Latvia was an obvious choice for Meduza because of the ease of setting up a business there and its proximity to Russia. “You don’t really feel foreign there,” said Kovalev.

But remote teamwork can be hard. “The physical disconnection between the teams, holding editorial meetings every day on Google Hangouts, can be very tiresome,” said Kovalev. “It’s demoralizing to work alone.”

It can also be challenging to adhere to both Russian and Latvian law, for example on how to refer to Crimea, the territory Russia annexed from Ukraine in 2014. The European Union, of which Latvia is a member, does not recognize the annexation. In Russia, it’s a criminal offense to challenge “Russia’s territorial integrity,” including the status of Crimea.

“You’re damned if you do, damned if you don’t call Crimea Russian,” said Kovalev. “So we keep two in-house lawyers — one Latvian and one Russian.”

Maintaining Independence

Turkish editor Can Dündar was flanked by bodyguards as he spoke at the Global Investigative Journalism Conference in Hamburg last September. Turkish President Recep Tayyip Erdogan has labeled him a traitor. His face is well-known and he’s regularly harassed by pro-Erdogan supporters, even in Germany.

When Erdogan came to Germany in September 2018, the Turkish president refused to go to a press conference if Dündar was there. “Unfortunately, you find yourself to be a political figure rather than a journalist when you go to exile,” Dündar said.

He struggles with this new identity. German colleagues caution him against being too activist-like and, as a former journalism lecturer, Dündar used to give his students the same advice. “But imagine that your house is burning and people expect you to just take pictures of it,” he said. “We are not only journalists; we are fathers, mothers, human beings.”

“I’m always struggling to not feel like an activist,” said Scharfenberg, from Armando.info. “We have to be restrained by the rules of journalism. It’s the only way we can preserve our capital, which is reputation.”

Sometimes Scharfenberg wonders if Armando.info’s Venezuelan audience really wants to consume investigative reporting. “In a society that is as polarized as ours, both sides want information to weaponize it, to use it against the other,” he said. When Armando.info published corruption investigations about the Venezuelan opposition as well as the government, some opposition supporters turned on them.

It can be frustrating to be attacked by all sides, but Scharfenberg is convinced that independent investigative journalism from exile is vital work. “Exile is the natural destination of the dissidents, so it becomes very fertile ground for propaganda against the government,” he said. “I think it’s important to show the difference, and to show that it is still possible to do journalism.”