Already one of the biggest jailers of journalists in the world, Turkey under President Recep Tayyip Erdogan is now turning the screws on the handful of independent media outlets left as the government seeks to silence criticism of its handling of the COVID-19 pandemic, media watchdogs and experts say.

Since a failed coup in mid-2016, authorities under Erdogan have closed 70 newspapers, 20 magazines, 34 radio stations and 33 television channels, accusing them of ties to ‘terrorism’ and the man they allege masterminded the abortive putsch, US-based cleric Fethullah Gulen.

A handful of independent outlets remain, but they too now face fresh pressure over their coverage of Turkey’s efforts to tackle the rapid spread of the novel coronavirus and its impact on the country’s already shaky economy.

The state broadcasting regulator, Radio and Television Supreme Council, RTUK, recently fined several TV channels over their coverage of the government’s COVID-19 strategy, including FOX TV, broadcaster of Turkey’s most watched television news show anchored by Fatih Portakal.

On April 7, the regulator banned Portakal’s show for three days, accusing him of bias.

If FOX TV is fined once more for the same reason, it risks losing its licence. The broadcaster has appealed the decision but there has been no official response.

Erdogan has also weighed in personally, suing Portakal for spreading lies and manipulating the public. The anchor faces a potential prison sentence of three years.

“Some media and politicians are more dangerous than the virus,” Erdogan said on April 13. “They attack and criticise the government instead of supporting it in these difficult days, but our country will get rid of media and political viruses very soon.”

Critics of the government say it fears for its political future after losing a number of key Turkish cities to the opposition in local elections last year, with the economic crisis worsening since the onset of the pandemic.

Gokhan Durmus, General Secretary of the Journalists’ Union of Turkey, TGS, said the saga over Portakal and FOX was symptomatic of the government’s treatment of the press.

“The pressure and investigations against the media increased during the pandemic,” Durmus told BIRN. “In particular, media institutions and journalists who question or criticise government measures face a serious threat from the government via fines, legal investigations and blackmail.”

Government fears for its future – expert

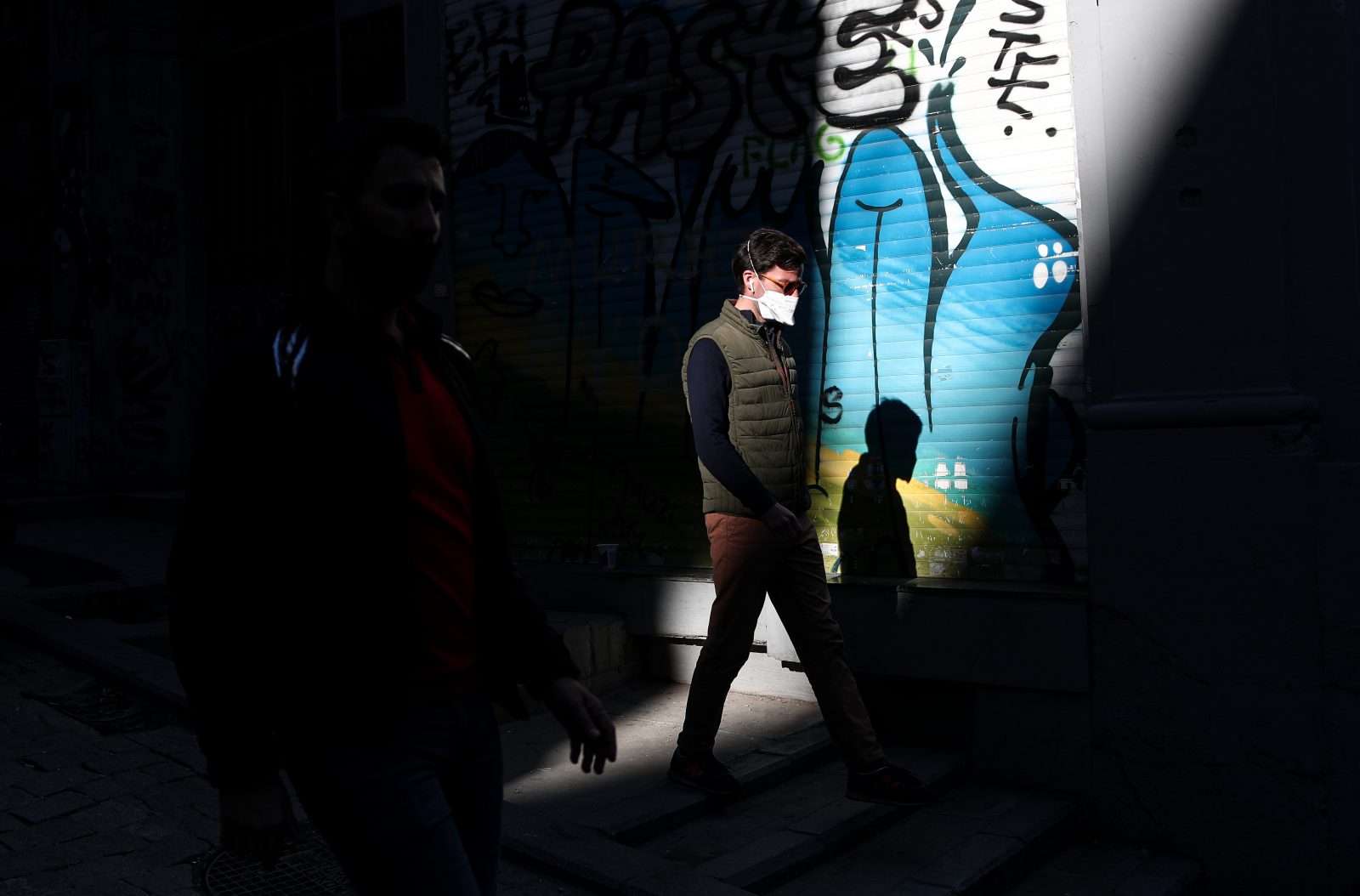

A Turkish policeman with face mask blocks the main road during curfew in Istanbul, Turkey, 2020. Photo: EPA-EFE/TOLGA BOZOGLU

With some 139,000 confirmed cases and 3,786 deaths as of May 11, Turkey has been hit hard by the pandemic, piling pressure on a government already struggling on the economic and political front.

Media watchdog Reporters without Borders ranks Turkey 154th out of 180 countries in terms of media freedom, characterising the country as “not free” on its Press Freedom Index.

According to this year’s Turkish Press Freedom Report, published on May 3, 85 journalists are in Turkish prisons and 103 journalists arrested and awaiting trial.

The report says that, between April 2019 and April 2020, RTUK applied administrative sanctions against television broadcasters in 20 cases and halted the broadcasting of 16 channels.

It also said that over 80 per cent of Turkish journalists believe they suffer from censorship and more than 78 per cent say they self-censor.

Mehmet Onur Cevik, an expert on Turkish media and politics at the University of Ghent in Belgium, said Erdogan and his ruling Justice and Development Party, AKP, already control 90 per cent of the media in Turkey.

“However,” he said, “the government left a small floor to a certain degree of independent and critical media as well as opposition parties.”

The AKP uses the existence of a small number of independent media outlets, as well as democratic elections, “to prove its political legitimacy against accusations of being authoritarian and oppressing its critics,” Cevik said.

“However, now things have changed because the economic crisis has deepened following the COVID-19 pandemic and people speak more about the government’s wrongdoings.”

The ruling party has gone on the offensive, he told BIRN, “since for the first time they fear for their political future. They fear that even news about the worsening economy can trigger a tsunami.”

Intolerance of criticism

A group of workers disinfect the Turkish Parliament General Assembly to prevent the spread of the novel coronavirus in Ankara, Turkey, 2020. Photo: EPA-EFE/STR

RTUK and Turkey’s Press Ad Agency, BIK, which controls state advertising spending, are state institutions originally established to protect journalists, regulate their work and make sure media across the board are on a secure financial footing.

“However, in the last two years, these institutions started to do what the government wants and they turned into the government’s hammer,” said Durmus.

“Journalists face continuous legal investigations and the penalties from Turkish state institutions such as RTUK and intensified in recent years. Just during the pandemic, 13 journalists have been detained because of their coverage.”

“The government does not want to hear anything that differs from its own opinion,” said Durmus. “With these recent penalties and continuous pressure, the government indirectly told journalists that they will be fined if they say anything critical about the government’s policies.”

After years of economic crisis, the government has been caught short on firepower to deal with the COVID-19 pandemic and is trading political blows with opposition-run cities.

In what critics say is a blatant bid to control the narrative, the government announced new legislation on May 7 concerning ‘manipulation’ of financial markets and targeting allegedly “deceptive” news about the economy.

It has also tabled to parliament a new law on digital rights, to the alarm of rights groups which say it will increase government control over social media platforms and potentially force some to quit the country.

“The AKP had never been so uncomfortable with independent media, social media and the opposition, because it feels that its rule is being threatened,” said Cevik.

“So they target the media, opposition and whoever thinks differently, even at the cost of losing legitimacy.”