Here is an easy step by step guide to formulating an investigation.

Step 1: Finding a story

Films such as All the President’s Men have shaped how the public, and even many reporters, view the work of investigative journalists.

Hollywood screenwriters would have you believe it is a shadowy world of clandestine meetings, codenames and tussles with the security services.

A tiny minority of stories do play out like movies – we have, after all, had cinema adaptations of the Edward Snowden leaks and The Guardian’s relations with Wikileaks recently – but most investigative journalism is much more mundane, although no less important.

You will need to work hard to develop your sixth sense – your ability to spot the unusual, the unexplained or patterns that will lead you to your next investigation.

It helps to be inquisitive and curious by nature, but you can teach yourself to sniff out those great untold stories.

Here are a few tips to build up your skills.

Spotting the unusual

To be an investigative journalist you must be able to quickly spot the unusual – what I call “smell a rat”. Without that sixth sense, stories will pass you buy and you will miss key details in your research.

Part of this skill comes from practice, but the tips in this chapter should help you sharpen your eye to those potential story ideas.

Take a careful look at this press release from the EU Rule of Law Mission and ask yourself whether there is more to this story than meets the eye:

Press release – the Son of the Kurdish President:

Indictment confirmed against six suspects in the Spain theft case

10 July 2012

A local judge at the Prishtine/Pristina District Court confirmed the indictment filed by a EULEX prosecutor against six suspects, one of them a high-ranking ROSU officer, in connection with a theft that took place in Barcelona, Spain in July 2009.

The indictment was confirmed against Haki Januzi, Artan Xhaferi-Jelliqi, and Shemsedin Benarba who are charged with the criminal offence of aggravated theft. Artan Xhaferi-Jelliqi is also charged with unauthorized control, possession or use of weapons.

The judge confirmed the indictment against Afrim Ymeri, Abedin Beka and Saim Januzi who are charged with the criminal offence of providing assistance to perpetrators after the commission of a criminal offence.

The confirmation judge found that the evidence supports the grounded suspicion that the suspects committed the criminal offences they are charged with.

The indictment was severed against Sami Makolli because the suspect was not present in court during the confirmation hearing.

The judge did not hold a confirmation hearing for Erhan Berniqani, Dusan Kadijevic, Nebojsa Bojvic and Afrim Ymeri charged with the criminal offence of receiving stolen goods, since these charges are handled through a summary procedure.

The defendants are accused in connection with the theft of approximately 1.3 million Euros worth of jewellery in a hotel room in Barcelona, Spain.

The case is being prosecuted in a mixed team led by a EULEX District Prosecutor.

The press release appears to a pretty standard announcement of an indictment for an unremarkable crime, until you reach the second to last line.

When I read this, the immediate question which jumped out of the page was what kind of person would own at least 1.3 million euro worth of jewellery, travel with it and then leave it in a hotel room? The answer is someone who is grossly rich with perhaps a reckless approach to security.

After obtaining further court documents, BIRN was able to confirm that the victim of this crime was the son of the Kurdish President, who had been gambling in Barcelona’s casino during an extended stay. This raised further questions about how he had accumulated such wealth and what he was doing in Barcelona.

An alternative investigation which reporters could have carried out would have delved into how this Balkan gang was operating in Barcelona, whether this was a one-off, how they operated and whether they were connected with other Balkan organised criminals, such as the notorious Pink Panthers.

Thus, from a simple press release, two excellent and intriguing investigations emerge demanding further attention.

Tackling the Press Release

The Press Release: A vector for much of modern journalism and a symbol of what is wrong with our trade. PR merchants and taxpayer-funded spin doctors spew out ‘media releases’ in the hope that journalists will be too lazy to do more than copy, paste, rewrite.

Press releases, however, can present a useful starting point for an investigation, revealing a great deal in a turn of phrase, its timing and its omissions. Here are a list of questions which are worth asking yourself when picking through one.

Why is the press release being issued? Is it pre-empting bad news (was it issued unusually late in the day for example)? Who issued it (which department or which press officer? Who is quoted (the more powerful the person quoted the more likely it is important even if at first sight it does not appear to be)?

Is the language and vocabulary clear? Is there deliberate use of vague or unusual terms?

What has been omitted from the release? Key details? Names? An important event?

Are there details which are unexpected or unusual which require further investigation?

Spotting the unusual, understanding the usual

As demonstrated by the previous example, a key part of investigative journalism is spotting the untold and unusual. You should be alert to this as you walk to work, attend a press conference or pour over thousands of pages of government paperwork.

Often, what is “unusual” will be very obvious – although it is by no means certain that journalists will follow it up. In a case involving the EULEX press release, we can all agree that it is unusual for someone to travel with 1.3million euro of jewellery. But, sometimes what is common and uncommon isn’t immediately apparent, particularly if you do not know the field well.

To spot the unusual, you must first understand what is usual in a certain context.

For example, it is usual for companies operating in the construction sector in Albania to be registered locally. It would be unusual if one of these is registered in the British Virgin Islands and if you discover this you should investigate.

The best way to increase your chances of spotting a story is to be well acquainted with the field you’re looking at and/or speak to someone who is.

It is impossible to build an exhaustive list of the “unusual” as each case is context-specific and you must let your journalist nous and common sense guide you to some extent but here are three red flags to look out for:

RED FLAG The presence of offshore companies: This is a tell-tale sign that something untoward is going on

RED FLAG Overly cautious, sketchy or aggressive statements from public bodies: In adversity and under pressure organisations, and humans, can react strangely. Remain vigilant for unusual behaviour.

RED FLAG Secretive and opaque processes: Where there is secrecy, a lack of transparency and money, there tends to be corruption – you only have to look at FIFA, or the scandal surrounding British MPs’ claims for expenses (to get taxpayers to pay for a duck house on a private lake or have a moat dredged!). When there are secrecy and haste in a particular process (the awarding of a mining licence or tender for example), this should also ring alarm bells.

Case study – Arms dealers arrested in Montenegro

In March 2015, a Serbian-Israeli consortium snapped up Montenegro’s state-owned arms-dealing firm.

While Israeli firms and dealers are major players in the secretive weapons market, it was still noteworthy that it was an Israeli firm, ATL Atlantic, which had partnered with Serbian company CPR Impex to buy Montenegro Defence Industries in March 2015.

This provided BIRN with the impetus to find out more about the deal and who was behind it.

Public records in Bulgaria, where ATL Atlantic had opened a subsidiary, revealed that it had recently been owned by a man named Serge Muller.

Following a brief internet search, two important leads emerged. The first was that Muller was a notorious arm and diamond dealer who had previously been linked to ATL Atlantic in Belgium.

The second was that Muller had been arrested under a Belgium arrest warrant in Montenegro at roughly the same time as the deal between the Montenegrin government and ATL Atlantic had been signed. This raised the important questions - was Muller still involved in ATL Atlantic and was he present at the signing ceremony?

Through various interviews, we were able to piece together Muller’s movements and demonstrate that he was arrested immediately after leaving the signing ceremony and that he continued to play a role, albeit an unofficial one, in ATL Atlantic. Following the publication of our story, the case was referred to the prosecutor.

This example demonstrates how a journalistic hunch – a sense that there is something unusual – can lead to important revelations.

Spotting the unreported in the reported

Many great investigations are hidden in plain sight. By that, I mean that all of the information is publicly available, often accessibly online and sometimes already in the media, but the full picture has not yet been pieced together.

This is often because journalists have failed to ask essential questions, hastily dispatching stories for a daily deadline.

You will, therefore, find many great leads for investigations in the unfinished work of your colleagues.

Case study – Veselinovic works for PDK-linked firm on Bechtel

It had been widely reported that Zvonko Veselinovic, the Serbian underground figure who had led the 2011 uprising against the Kosovo government, had worked on Kosovo’s 1billion euro highway.

Some sources had even reported that he had been involved in a quarry based in northern Kosovo, near the border with Serbia.

At the same time, other news outlets had reported how senior figures linked to the ruling Kosovo Albanian party of Hashim Thaci had opened a quarry in northern Kosovo.

Placing the two stories side by side, it is remarkable that no one had spotted the potential links between the two.

Using court testimony from Belgrade, publicly available documents and interviews with key figures, BIRN was able to conclude that Zvonko Veselinovic had provided logistical services to the PDK-linked firm, Arena Invest, and that this firm had secured a major contract from the firm constructing the highway.

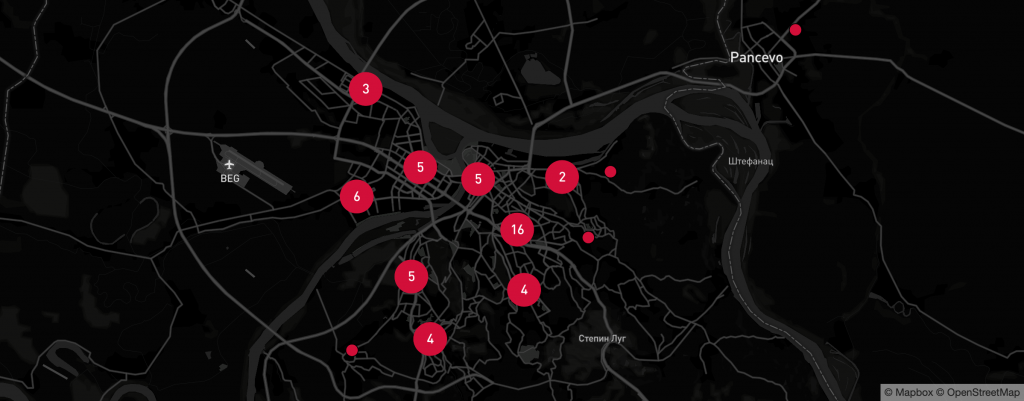

Spotting a pattern

Another useful technique to hone in on an investigation or to expand the scope of the story is to look for a pattern of events.

To do this you need to dissect the information you have, breaking it down into its most basic form. For a suspect tender, this would mean compiling a spreadsheet of the companies involved, owners, officials, addresses, telephone numbers and lawyers, for example.

You can then look at other tenders involving one or more of the elements above.

Step 2: Initial fact-finding

So you’ve spotted something unusual which has piqued your interest and after some basic research, you are beginning to form a picture in your head of what the story could be. This picture, or set of scenarios, is the beginnings of your investigative hypothesis.

Over the next few days or weeks, you will need to test this hypothesis and ask some searching questions about what the story is, how much it will cost to carry out, how much time is needed, what are the logistics of contacts and travel, and whether it is in the public interest.

At the end of this process, you will form an investigative hypothesis – combined with your minimum and maximum story which we will explain shortly – which will guide you throughout the investigation, providing you with clear demarcations of what your story is about and where it is heading.

Initial research to create a list of facts, and assumptions

Once you have a potential story, you need to refine it through some basic research. This will help you understand if your story is worth pursuing and to frame it. The time needed for this initial scoping will depend on how much you already know about the subject and its complexity.

The research should include:

- A thorough press review of all available material. You may need to use online media archives for this and, for course, Google. Many media organisations and NGOs now publish the source material for their work – check these carefully for leads.

- Use social media – Facebook, Twitter, Instagram and Google Plus – to build up an initial profile of your targets (see Chapter IV for more information)

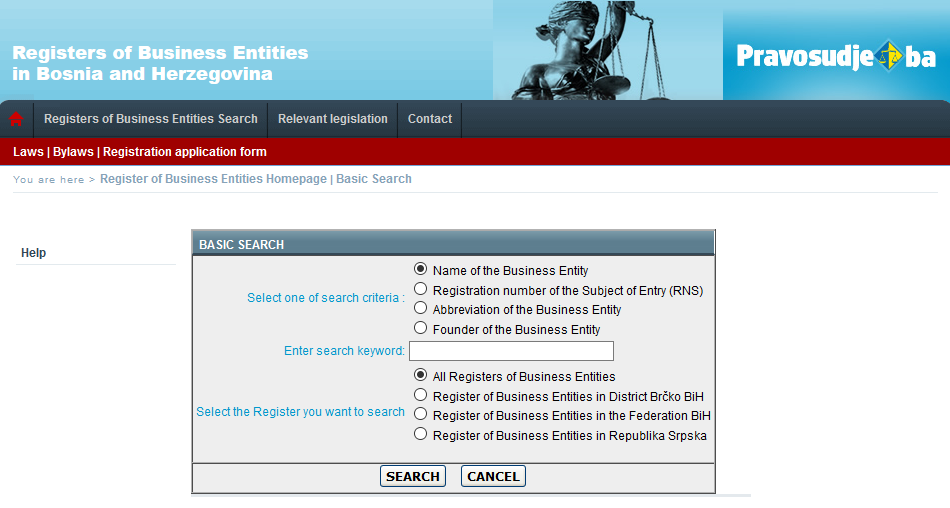

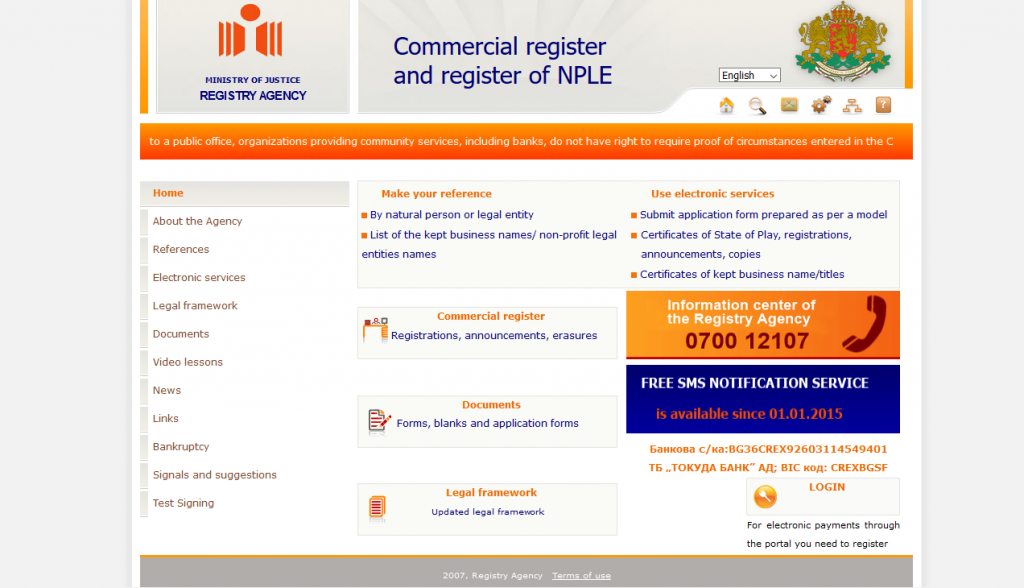

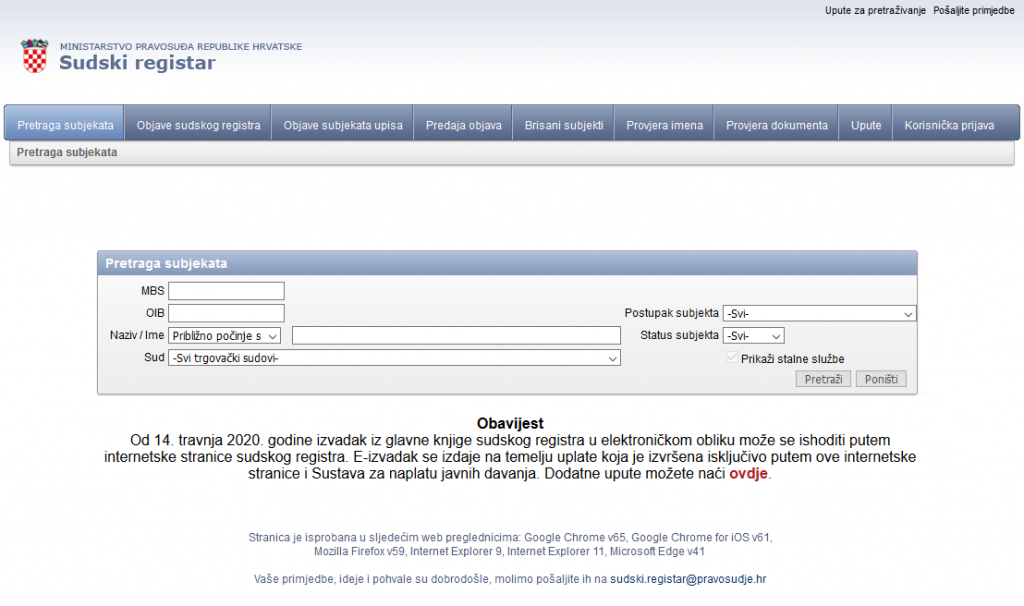

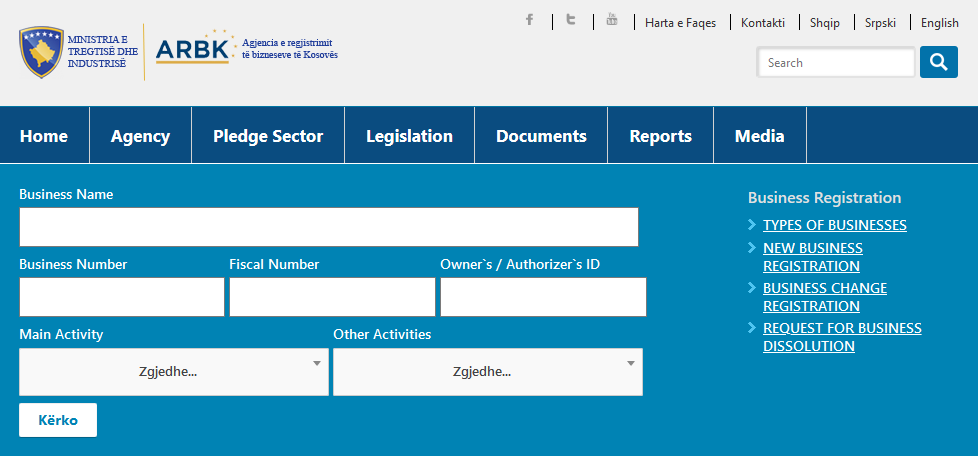

- Check other officials, online sources of material – government tenders, company registers, court documents, UN reports – to see if there is a pattern or other potential avenues of research.

- If there are books or academic and NGO reports about your chosen area of research then it is a good time to start reading. This will give you the in-depth knowledge to understand the world you are entering. You need to grasp the vocabulary and the processes involved in your subject matter if you are to fully investigate.

- Meet sources who could give you an overview of the subject or an indication of whether you are on the right track. Do not spend too long on this in the initial phase.

- Research the context of the story asking to determine why this issue important? Are there victims and who could they be?

- Attempt to work out the costs and time involved.

Create a list of bullet points which summarises your initial findings. These will allow you to later form your hypothesis.

Step 3: The feasibility question

Before you begin your investigation and frame your hypothesis, it is essential to ask yourself what documents are available and where you will find sources.

There is little point aiming for a story which you know will not be provable. This is not a time to be despondent about the lack of information available, but to carefully consider what you can reasonably expect to achieve.

Draw out a rough timeline of events, or a flowchart of how the system works, listing documents and people at each stage who are involved or will have knowledge of this. In this chain of events, look for the weakest links i.e. people who are most likely to talk.

Here is a helpful list of questions to use as a checklist.

- What documents are available and related to your subject matter? Can they be obtained through a public database? Freedom of Information request? Which institutions hold copies? Are there relevant court cases? Commercial disputes? What are the costs involved?

- What sources will have information relevant to the investigation? How many people are involved? Where do they work? How willing will they be to speak and what motivations may they have to blow the whistle or remain silent? Can you easily identify former employees? Who loses out? Who are the victims?

- How many and which countries are involved in the investigation? How could the international nature of the investigation help by providing extra sources of information or hinder by making the research more complex? Could you obtain information from more transparent jurisdictions?

- Are offshore entities involved? What are the major complications you are likely to face? Are there potential ways of bypassing tax haven secrecy?

Step 4: The pitch

Set a hypothesis

Your hypothesis is what you are seeking to prove (or disprove) and therefore will guide you through your investigation, who you will contact, which documents you will seek.

It is an extremely useful device to focus your thoughts but also to explain to your editor and collaborators what you are doing. Get your hypothesis right, and pitching your idea should be easy.

Many fields use a hypothesis to frame their work, from scientists to police officers, which is then tested throughout the research or investigation.

You will need to think carefully about what kind of information is available and how you will obtain it as there is little point setting a hypothesis which cannot be proved through journalist endeavour.

Your theory should provide answers to the classic what, when, who, why and how questions based on your initial research and your hunch.

Remember that it is easy to prove that events took place or decisions were made but very difficult to demonstrate the intentions behind them. For example, it is easy to prove that a minister awarded a contract to a friend, but it is far more difficult to prove that the minister awarded the contract to a friend because of their friendship.

Your hypothesis, in this case, may be that the contract was awarded because of the friendship, but do think carefully about how you can prove it.

Case Study: The Dahlan Investigation

When we discovered that famous Palestinian politician Mohammed Dahlan had been quietly and inexplicably handed a Serbian passport in 2013, we knew we had a good story idea which required further investigation.

We set about checking how this had happened and delving into how feasible the story was. Having explored the data we discovered these facts:

Dahlan, his wife and four children had been given citizenship in 2013 and 2014

Six other Palestinians had also been given citizenship over the same period, often at the same time as Dahlan family members. An initial search showed that these figures were supporters of Dahlan and had worked with him in the past

Citizenships tended to be awarded to prominent sporting and artistic figures, not politicians

No other Palestinians had been awarded citizenship in recent years

The decision had been taken by the Prime Minister and/or members of the cabinet

During this period Dahlan had been working with Abu Dhabi investors in Serbia, bringing the promise of billions of investment and had been honoured by the Serbian president for his bridge-building.

Mohammed Dahlan was under investigation at the time for corruption in Palestine.

From this we form this hypothesis:

Serbia’s government lavished passports on a group of controversial Palestinians in recompense for the work of Mohammed Dahlan in bringing gulf money to Serbia.

Define your maximum and minimum story

Investigations are complex and unpredictable, making it impossible to accurately predict the outcome, particularly as you rely on sources and public bodies which are beyond your control.

Even the best reporters using all the tools available to them need a bit of luck, particularly as cost and time constraints must be taken into account.

As a result, it is important to create a safety net by setting a minimum story which you can publish even if sources fail and documents do not materialise.

If your minimum story is still worthy of publication, then your project will not fail even if luck is not on your side.

Equally important is setting your maximum story. This provides you with your ultimate ambition if you collect all the documents you planned and all of the sources speak out.

With a hypothesis, minimum and maximum story pencilled out, you are ready to pitch your story to your editor and convince him or her that you really need to be taken off the daily news agenda to.

Step 5: Create a research plan

At this stage you know you have a story and you have successfully pitched it to your boss. It is time to create a research plan.

You should start by breaking down your story into stages in the process or events in a timeline.

From there, note what documents are created and used at each stage, who is involved in the process and who else would have access to the information.

Most stories can be broken down in this fashion, but if not then try to imagine all the interactions your person or company has with individuals, other companies and institutions (from the United Nations to small municipal councils). Make a note of these and the potential to obtain information.

You should then analyse each stage to determine to weakest links in the chain. Which institutions are likely to provide you with documents? Which individuals are likely to talk to you?

You should also consider the difficulty and time in obtaining the information or contacting people, (for example, Freedom of Information requests).

Write out your research plan (using a spreadsheet works well) and share it with your colleagues.

This article is originally published in BIRN Albania’s ‘Getting Started in Data Journalism’.