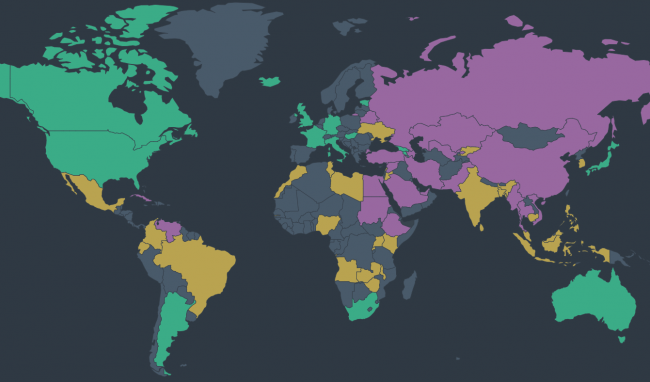

Freedom on the Net is a comprehensive study of internet freedom in 65 countries around the globe, covering 87 percent of the world’s internet users. It tracks improvements and declines in internet freedom conditions each year. The countries included in the study have been selected to represent diverse geographical regions and regime types. In-depth reports on each country can be found at freedomonthenet.org.

More than 70

analysts contributed to this year’s edition, using a 21-question research

methodology that addresses internet access, freedom of expression, and privacy

issues. In addition to ranking countries by their internet freedom score, the

project offers a unique opportunity to identify global trends related to the

impact of information and communication technologies on democracy.

Country-specific data underpinning this year’s trends is available online. This

report, the ninth in its series, focuses on developments that occurred between

June 2018 and May 2019.

Of the 65

countries assessed, 33 have been on an overall decline since June 2018,

compared with 16 that registered net improvements. The biggest score declines took

place in Sudan and Kazakhstan followed by Brazil, Bangladesh, and Zimbabwe.

In Sudan,

nationwide protests sparked by devastating economic hardship led to the ouster

of President Omar al-Bashir after three decades in power. Authorities blocked

social media platforms on several occasions during the crisis, including a

two-month outage, in a desperate and ultimately ineffective attempt to control

information flows. The suspension of the constitution and the declaration of a

state of emergency further undermined free expression in the country.

Harassment and violence against journalists, activists, and ordinary users

escalated, generating multiple allegations of torture and other abuse.

In

Kazakhstan, the unexpected resignation of longtime president Nursultan

Nazarbayev—and the sham vote that confirmed his chosen successor in

office—brought simmering domestic discontent to a boil. The government

temporarily disrupted internet connectivity, blocked over a dozen local and

international news websites, and restricted access to social media platforms in

a bid to silence activists and curb digital mobilization. Also contributing to

the country’s internet freedom decline were the government’s efforts to

monopolize the mobile market and implement real-time electronic surveillance.

The victory

of Jair Bolsonaro in Brazil’s October 2018 presidential election proved a

watershed moment for digital election interference in the country. Unidentified

actors mounted cyberattacks against journalists, government entities, and

politically engaged users, even as social media manipulation reached new

heights. Supporters of Bolsonaro and his far-right “Brazil over Everything, God

above Everyone” coalition spread homophobic rumors, misleading news, and

doctored images on YouTube and WhatsApp. Once in office, Bolsonaro hired

communications consultants credited with spearheading the sophisticated

disinformation campaign.

In

Bangladesh, citizens organized mass protests calling for better road safety and

other reforms, and a general election was marred by irregularities and

violence. To maintain control over the population and limit the spread of

unfavorable information, the government resorted to blocking independent news

websites, restricting mobile networks, and arresting journalists and ordinary

users alike.

Deteriorating

economic conditions in Zimbabwe made the internet less affordable. As civil

unrest spread throughout the country, triggering a violent crackdown by

security forces, authorities restricted connectivity and blocked social media

platforms.

China confirmed its status as

the world’s worst abuser of internet freedom for the fourth consecutive year. Censorship reached unprecedented

extremes as the government enhanced its information controls in advance of the

30th anniversary of the Tiananmen Square massacre and in the face of widespread

antigovernment protests in Hong Kong. In a relatively new tactic,

administrators shuttered individual accounts on the hugely popular WeChat

social media platform for any sort of “deviant” behavior, including minor

infractions such as commenting on environmental disasters, which encouraged

pervasive self-censorship. Officials have reported removing tens of thousands

of accounts for allegedly “harmful” content on a quarterly basis. The campaign

cut individuals off from a multifaceted tool that has become essential to

everyday life in China, used for purposes ranging from transportation to

banking. This blunt penalty has also narrowed avenues for digital mobilization

and further silenced online activism.

Internet

freedom declined in the United States. While the online environment remains

vibrant, diverse, and free from state censorship, this report’s coverage period

saw the third straight year of decline. Law enforcement and immigration

agencies expanded their surveillance of the public, eschewing oversight,

transparency, and accountability mechanisms that might restrain their actions.

Officials increasingly monitored social media platforms and conducted

warrantless searches of travelers’ electronic devices to glean information

about constitutionally protected activities such as peaceful protests and

critical reporting. Disinformation was again prevalent around major political

events like the November 2018 midterm elections and congressional confirmation

hearings for Supreme Court nominee Brett Kavanaugh. Both domestic and foreign

actors manipulated content for political purposes, undermining the democratic

process and stoking divisions in American society. In a positive development

for privacy rights, the Supreme Court ruled that warrants are required for law

enforcement agencies to access subscriber-location records from third parties.

Only 16

countries earned improvements in their internet freedom scores, and most gains

were marginal. Ethiopia recorded the

biggest improvement this year. The April 2018 appointment of Prime Minister

Abiy Ahmed led to an ambitious reform agenda that loosened restrictions on the

internet. Abiy’s government unblocked 260 websites, including many known to

report on critical political issues. Authorities also lifted a state of

emergency imposed by the previous government, which eased legal restrictions on

free expression, and reduced the number of people imprisoned for online

activity. Although the government continued to impose network shutdowns, they

were temporary and localized, unlike the nationwide shutdowns that had occurred

in the past.

Other

countries also benefited from an opening of the online environment following

political transitions. A new coalition government in Malaysia made good on some

of its democratic promises after winning May 2018 elections and ending the

six-decade reign of the incumbent coalition. Local and international websites

that were critical of the previous government were unblocked, while

disinformation and the impact of paid commentators known as “cybertroopers”

began to abate. However, these positive developments were threatened by a rise

in harassment, notably against LGBT+ users and an independent news website, and

by the 10-year prison term imposed on a user for Facebook comments that were

deemed insulting to Islam and the prophet Muhammad.

In Armenia, positive changes

unleashed by the 2018 Velvet Revolution continued, with reformist prime

minister Nikol Pashinyan presiding over a reduction in restrictions on content

and violations of users’ rights. In particular, violence against online

journalists declined, and the digital news media enjoyed greater freedom from

economic and political pressures.

Iceland became the world’s

best protector of internet freedom, having registered no civil or criminal cases against

users for online expression during the coverage period. The country boasts

enviable conditions, including near-universal connectivity, limited

restrictions on content, and strong protections for users’ rights. However, a

sophisticated nationwide phishing scheme challenged this free environment and

its cybersecurity infrastructure in 2018.