Cameras on a mast. Photo: EPA-EFE/ARTUR RESZKO POLAND OUT

Albanian police said on Monday that they are investigating illegal surveillance cameras installed in the northern city of Shkoder, three days after they removed them in an operation.

Eight cameras were placed in squares of the city and 13 in a road. All were connected with mobile phones.

Asked if any of the authors had been detained, police in Shkoder said that “investigations were still ongoing” and that “the penalty for this crime is a fine”.

A police statement on Saturday said: “The cameras installed by persons or criminal groups were also intended to obtain information about the movements of the police”, and that they were working to identify the authors and their motives.

The areas where the cameras were placed are known to be related to local criminal groups.

The city is a known hotspot for serious organized crime, with gangs being responsible for a series of killings in public spaces, often warning each other with “explosive attacks”. Drug cultivation is widespread, especially in the rural surrounding areas.

The placement of the cameras was seen as a clear sign of organized groups controlling the territory, though the exact time of the placement is unknown.

Media reported on Sunday that two people were questioned by the police related to the cameras but the final author remains unclear because the investigators need to find the server from which the cameras were being controlled.

The installation of such cameras is against the law on “Protection of personal data” and constitutes the crime of “Unjust interference in private life”, which says that the illegal placement of recording devices that expose the private lives of people without their consent is a crime punishable by a fine or up to two years in jail.

Placement of illegal CCTVs has become common elsewhere in the region.

In April 2016, Montenegrin police found 21 illegal CCTVs erected in 11 locations in the coastal town of Kotor. The UNESCO-protected town is known for its war between rival drug gangs that trace their roots to two Kotor neighborhoods, Skaljari and Kavac.

The conflict started in 2015 after 300 kilos of cocaine vanished from an apartment in Valencia, Spain, in 2014. At least 40 people have been killed in Montenegro, Serbia, Austria and Greece in the conflict.

During raids, Kotor police found several receivers of illegal CCTVs, owned by suspected drug gang members. In April 2016, illegal CCTVs were also found in the capital Podgorica in the neighborhoods of Zagoric and Gorica. In September 2016, Special State Prosecution opened an investigation into illegal CCTVs but there were no charges filed so far.

Western Balkan countries faced by cyber attacks since July (illustration). Photo: EPA-EFE/SASCHA STEINBACH

Western Balkan countries faced by cyber attacks since July (illustration). Photo: EPA-EFE/SASCHA STEINBACH

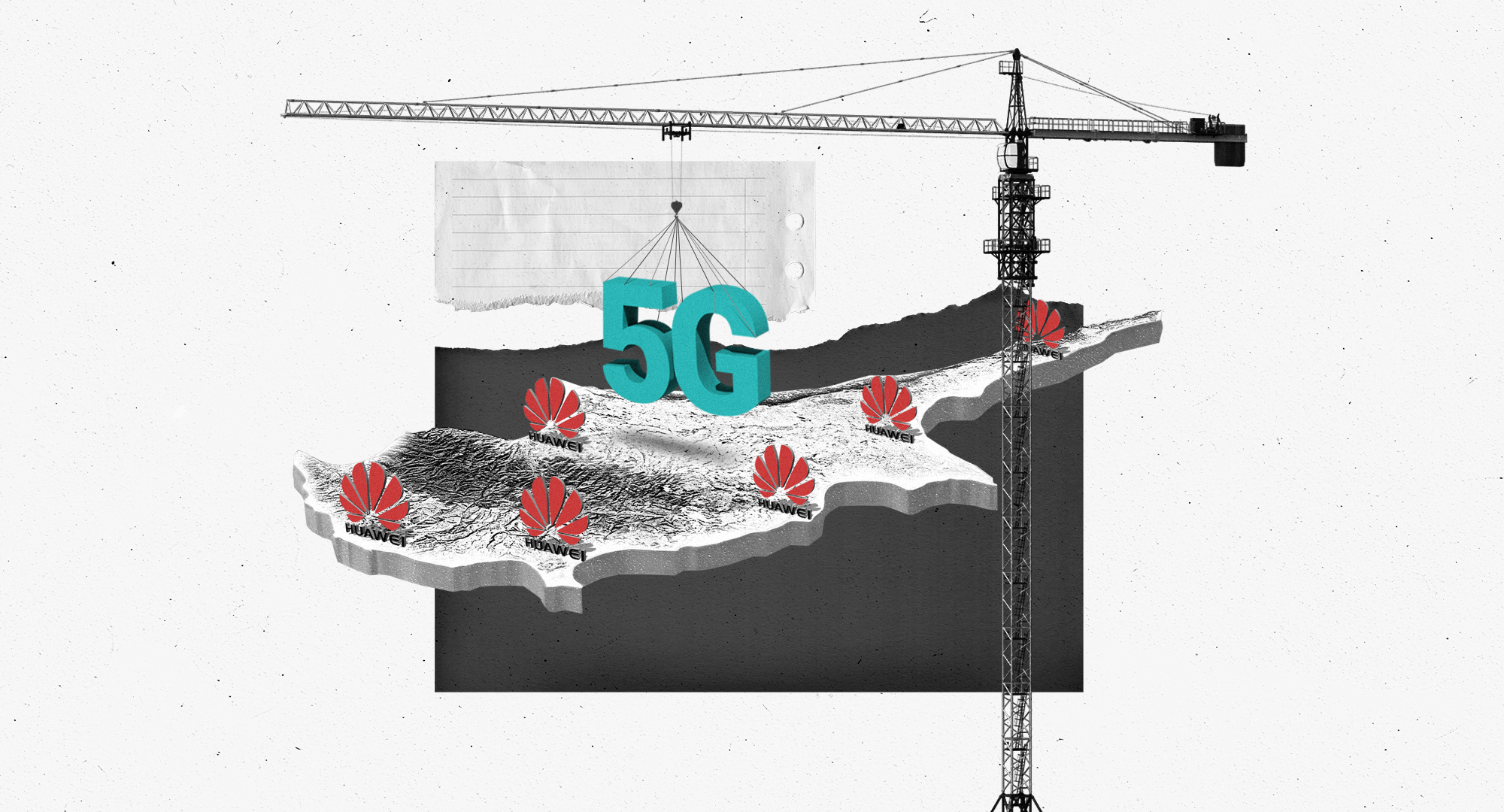

Illustration: BIRN/Igor Vujcic

Illustration: BIRN/Igor Vujcic Huawei (Nicosia)-the building in which Huawei’s main Cyprus offices reside. Photo: BIRN

Huawei (Nicosia)-the building in which Huawei’s main Cyprus offices reside. Photo: BIRN

Mediterranean Hospital of Cyprus (Limassol),one of two Cypriot hospitals to partner with VeChain store vaccination records on the VeChainThor blockchain. Photo: BIRN

Mediterranean Hospital of Cyprus (Limassol),one of two Cypriot hospitals to partner with VeChain store vaccination records on the VeChainThor blockchain. Photo: BIRN Passport control at the derelict former Nicosia International Airport in Nicosia, Cyprus. Photo: EPA/JAN RAKOCZY

Passport control at the derelict former Nicosia International Airport in Nicosia, Cyprus. Photo: EPA/JAN RAKOCZY