In the age of the digital revolution, where artificial intelligence, AI, intertwines with our daily lives, a profound ethical dilemma has arisen. This dilemma has shaken the foundations of truth, especially in the realm of media reporting. This specter goes by many names, but we commonly know it as “fake news”.

AI significantly facilitates all aspects of people’s daily and business lives but also brings challenges. Some ethical issues arising from the development and application of AI are alignment, responsibility, bias and discrimination, job loss, data privacy, security, deepfakes, trust, and lack of transparency.

AI has tremendously impacted various sectors and industries, including media and journalism. It has created different tools for automating routine tasks that save time and enhance the accuracy and efficiency of news reporting, content creation, and personalizing content for individual readers, enhancing ad campaigns and marketing strategies.I

At the same time, AI poses enormous ethical challenges, such as privacy and transparency and deepfakes. Lack of transparency leads to biased or inaccurate reporting, undermining public trust in the media. There’s the question of truth: How do we discern fact from fabrication in an age where AI can craft stories so convincingly real? Further, there’s the matter of agency: Are we, as consumers of news, becoming mere pawns in a giant game of AI-driven agendas?

There are several studies examining public perception of these issues. Research done at the University of Delaware finds that most Americans support the development of AI but also favor regulating the technology. Experiences with media and technology are linked to positive views of AI, and messages about the technology shape opinions toward it.

Most Americans are worried that the technology will be used to spread fake and harmful content online (70 per cent). In Serbia a study has been conducted of public attitudes towards AI within the research project Ethics and AI: Ethics and Public Attitudes towards the use of AI.

The results showed that although most respondents have heard of AI, 4 per cent of them do not know anything about AI. Respondents with more knowledge about AI also have more positive attitudes towards its use. It has been shown that people are more informed about AI through the media compared to being informed about this topic through education and profession.

To the statement, “I am afraid that AI will increasingly be used to create fake content (video, audio, photos), and that there is digital manipulation,” 15.2 per cent gave a positive answer, while 62.4 per cent gave a negative response (22.4 per cent are neutral about this question). These results suggest a need to educate the public about potential challenges and ways to prevent them.

Grappling with AI’s Dual Role in Shaping and Skewing News

Illustration: Unsplash.com

According to the Cambridge Dictionary, fake news is defined as false stories that appear to be news spread on the internet or using other media, usually created to influence political views, or as a joke. The Oxford English Dictionary defines fake news as false news stories, often of a sensational nature, designed to be widely shared or distributed to generate revenue or promote or discredit a public figure, political movement, company, etc. Fake news often has propaganda, satire, parody, or manipulation elements.

Other forms of fake news are misleading content, false context, impostor, manipulated, or fabricated content. Fake news has increased on the internet, especially on social media. After the 2016 US elections, fake news dominated the internet. In May this year, posts about the death of the American billionaire George Soros on social media turned out to be fake news.

There is ongoing active research on numerous tactics to combat fake news. Authorities in both autocratic and democratic countries are establishing regulations and legally mandated controls for social media platforms and internet search engines. Google and Facebook introduced new measures to tackle fake news, while the BBC and the UK’s Channel 4 have established fact-checking sites. In Serbia, there is FakeNews Tracker, a portal that searches for inaccurate and manipulative information. The portal is dedicated to the fight against disinformation in media that publish content in the Serbian language.

The mission of the FakeNews Tracker is to encourage the strengthening of media integrity and fact-based journalism. When you see suspicious news, you can report it through the form on their page, after which they check the news. If they find it fake, they publish an analysis. In neighbouring Croatia, a similar fact-checking media organization is Faktograf.

On the individual level, we need to develop critical thinking and be careful when sharing information. Digital media literacy and developing skills to evaluate information critically are essential for anyone searching the internet, especially for young people. Confirmation bias can seriously distort reasoning, particularly in polarised societies.

How AI is Reshaping the Balkan Media Landscape

How does AI shape fake news? AI can be used to generate, filter, and discover fake news. AI’s power to simulate reality, generate human-like texts, and even fabricate audiovisual content has enabled fake news to flourish at an unprecedented rate. There are fake news generators and fake news trackers.

A recent example of the first usage was the news about Serbia ordering 20,000 Shahed drones from Iran, which AI entirely generated. It was then published by some major and credible media outlets. Bosnian media published this news under the headline “Serbia is arming itself”. It turned out that AI made a mistake. Serbia’s Deputy Foreign Minister Aleksić did visit Tehran and met his Iranian counterpart Ali Bagheri. However, there was no information about Serbia ordering Shahed drones. Another example is deepfake, a video of a person whose face or body has been digitally altered to appear to be someone else, typically used maliciously or to spread false information.

Previously, the victims included Donald Trump and Vladimir Putin, and recently, Serbia’s Freedom and Justice Party president, Dragan Đilas. The owner of Serbia’s Pink TV, Željko Mitrović, created a satire with the help of AI technology in which Đilas is a guest on the show Utisak Nedelje and pronounces fictional content generated by deepfake technology. The problem is that the fabricated statements were shown in Pink’s evening news bulletin (Nacionalni dnevnik) without the audience being adequately informed that it was a satirical fabricated speech while it was running. This is an example of misuse of AI.

Announcing a series of legal measures against the owner of Pink, including a lawsuit, Đilas appealed for the new regulation to prohibit the editing of such recordings because they contradict the fundamental guarantees of the European Convention on Human Rights and the Personal Data Protection Act. He also pointed out that this is very dangerous and that the statements of state representatives can be falsified in the same way, endangering the entire country.

AI, with its labyrinthine algorithms and deep learning capabilities, can shape our perceptions more than any propaganda leaflet or radio broadcast of yesteryears.

AI in the media can also detect and filter fake news. Deep learning AI tools are now being used to source and fact-check a story to identify fake news. One example is Google’s Search Algorithm, designed to stop the spread of fake news and hate speech. Websites are fed into an intelligent algorithm to scan the sources and predict the most accurate and trustworthy versions of stories.

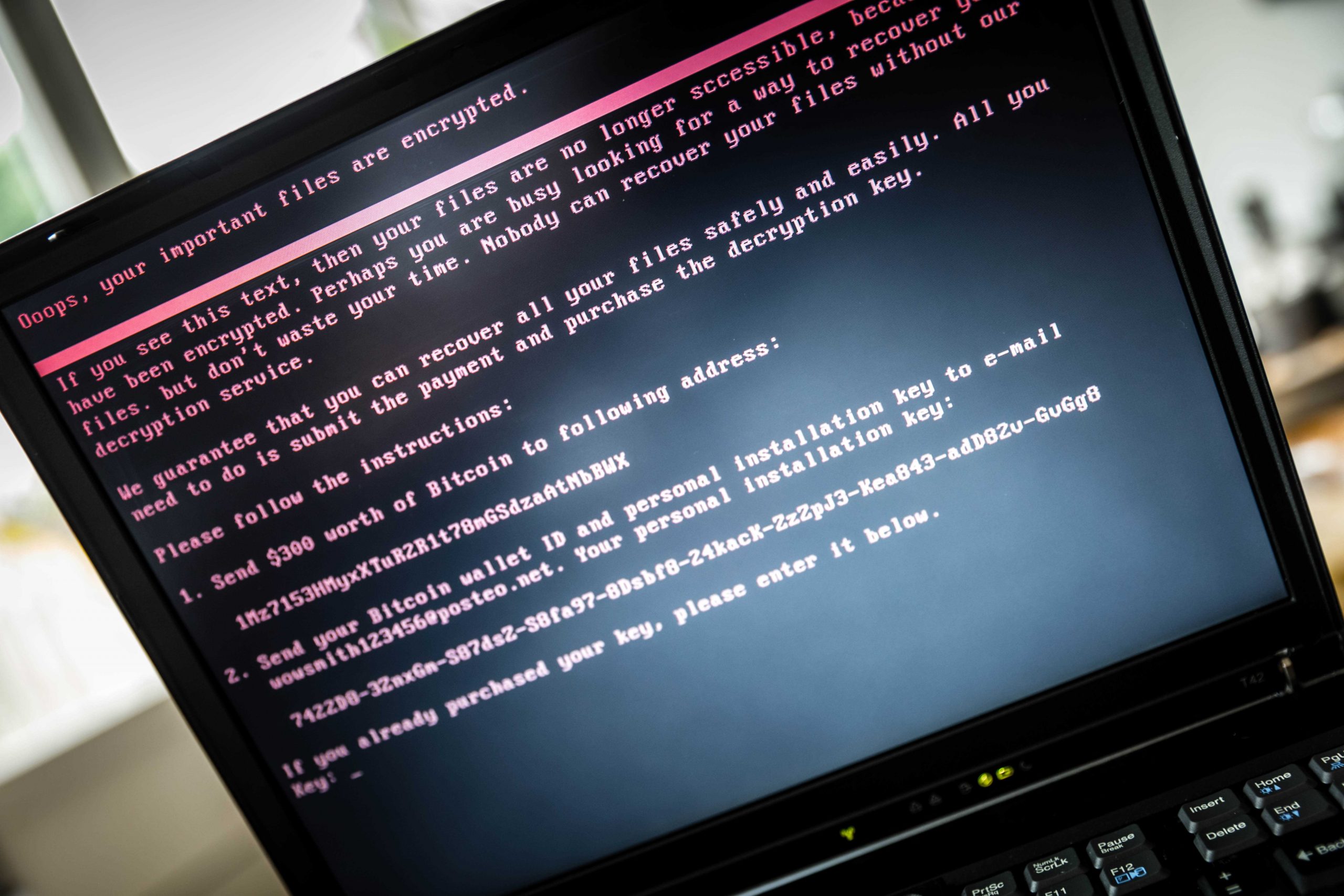

Illustration: Unsplash.com

Why should the Balkans care? This region, marked by its tumultuous history, fragile relationships between these countries, and diverse ethnic tapestry, is especially vulnerable. AI-driven disinformation can easily rekindle past animosities or deepen current ones. Recent incidents in Serbia, where AI-generated stories incited unnecessary panic, are poignant reminders. Furthermore, the Balkans, like the rest of the world, face a constant battle over media trust. A single AI-generated yet convincingly real misinformation campaign can erode already waning trust in genuine news outlets.

This debate raises the question: Is freedom of speech more important than the potential for harming fake news and deceptions? I would vote for freedom of speech, but speech that is informed and veridical.

To tackle this, we need strategies:

- Enhanced Media Literacy and Education: Educational institutions across Serbia and its neighbours should integrate media literacy into their curricula. As a part of school curricula and community workshops across the Balkans, media literacy can arm the population with the critical thinking tools needed in this digital age. By teaching individuals to critically evaluate sources, question narratives, and understand the basics of AI operations, we’re equipping them with tools to discern the real from the unreal.

- Transparent Algorithms: The algorithms behind AI-driven platforms, especially those in the media space, should be transparent. This way, experts and the public can scrutinize and understand the mechanics behind information dissemination.

- Ethical AI Development: AI developers in Serbia and globally need to embed ethical considerations into their creations.

- Regulatory Mechanisms: While over-regulation can stifle innovation, a balanced approach where AI in media is subjected to ethical guidelines can ensure its positive use.

- Collaborative Monitoring: Regional collaboration can create a unified front against fake news. Media outlets across the Balkans can join forces to fact-check, verify sources, and authenticate news, thereby ensuring a cleaner information environment.

- Public-Private Partnerships: Tech companies and news agencies can forge alliances to detect and combat fake news. With tech giants with vast resources and advanced AI tools, such partnerships can form the first line of defense against AI-driven misinformation.

It is evident that AI will be shaping the future of media and journalism. The challenges AI poses in media reporting, particularly in the propagation of fake news, are significant but not insurmountable. Finding the proper equilibrium between maximizing AI’s advantages and minimizing its possible dangers is essential. This necessitates continuous dialogue and cooperation among journalists, tech experts, and policymakers.

With a harmonized blend of education, transparency, ethical AI practices, and collaborative efforts, Serbia and the entire Balkan region can navigate their way through the shadows of this digital cave, ensuring that truth remains luminous and inviolable.

Marina Budić is a Research Assistant at the Institute of Social Sciences in Belgrade. She is a philosopher (ethicist), and she conducted a funded research project, Ethics, and AI: Ethics and public attitudes towards the use of artificial intelligence in Serbia, and presented her project at the AAAI/ACM Conference on AI, Ethics, and Society (AIES) at Oxford University 2022.

The opinions expressed are those of the author only and do not necessarily reflect the views of BIRN.