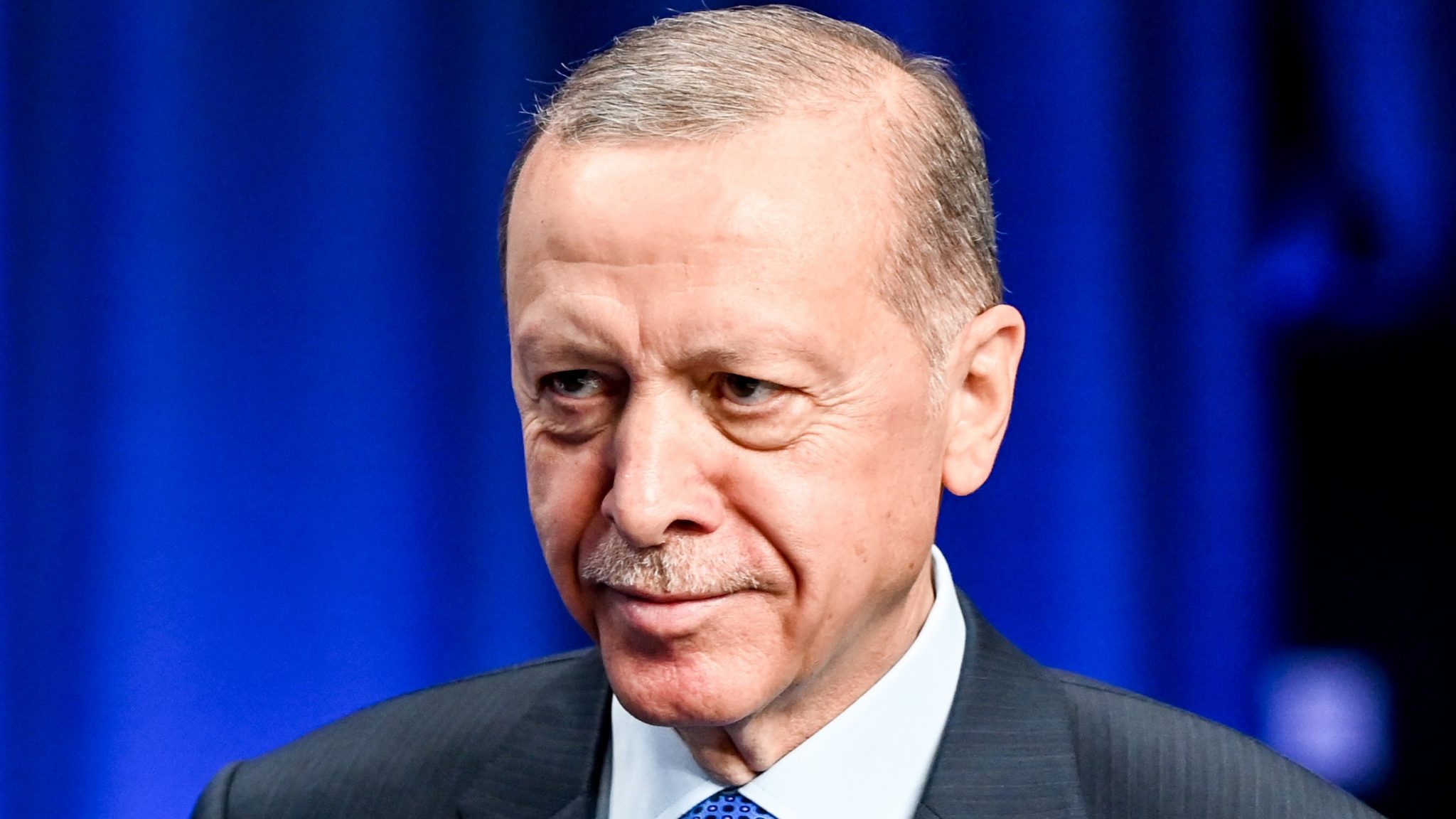

In the wake of devastating twin earthquakes in February, and with May elections fast approaching, President Recep Tayyip Erdogan issued a warning to critics of his government in the media coverage of its response to the crisis: “We will never forget them”.

Data from the Mapping Media Freedom project of the European Centre for Press and Media Freedom, ECPMF, suggest that Erdogan, having turned the tables on the opposition, has kept his word when it comes to Turkish journalists.

Of 154 violations of media freedom reported in Turkey since the start of 2023, 48, or almost a third, have come since the May elections won by Erdogan and his Justice and Development Party, AKP.

Europe-wide, the ECPMF has registered 671 violations so far this year, meaning Erdogan’s Turkey alone accounts for almost one quarter. This year’s tally of 154 violations so far compares with 33 for the whole of 2020, 92 in 2021, and 167 in 2022.

According to Gurkan Ozturan, project coordinator of Media Freedom Rapid Response at the ECPMF, “in 2023 we have observed a spike in censorship with a steep increase in the number of access blocking orders since the beginning of the year”.

“Legal incidents still make up the biggest part of the violations targeting journalists, media workers and outlets,” he told BIRN.

Earthquakes and economy

The May elections were billed by many as the last chance to save Turkish democracy after 21 years of increasingly authoritarian rule by Erdogan and his AKP. Rocked by criticism of their response to the earthquakes in February and their handling of the economy, both Erdogan and AKP appeared to be on the ropes. But the many pundits and pollsters who predicted an opposition win were wrong.

Erdogan wasted no time in exacting revenge on the media outlets and journalists that sided against him.

“Starting from the night of the elections, we have been seeing Erdogan’s statement become a reality,” said Ozturan.

“Multiple officials from the governing alliance have also made threatening remarks against independent media and, as a result, now we are seeing the negative developments continue in the field of journalism.”

Since May 14, the ECMPF has documented 230 media alerts across Europe, 48 of them originating in Turkey.

One of the most prominent and widely condemned was the arrest in late June of veteran journalist Merdan Yanardag, managing editor of TELE 1 TV, after he called for strict measures imposed on jailed Kurdistan Workers’ Party, PKK, leader Abdullah Ocalan – such as solitary confinement – to be lifted. He described Ocalan as “an extremely intelligent person who reads politics correctly, sees it correctly, and analyses it correctly”, comments for which Yanardag was taken into custody and accused of ‘praising a crime and a criminal’ and ‘propaganda for a terrorist organisation’.

Yanardag remains in prison awaiting trial, and for seven days in July TELE 1 TV’s screens were blanked by the government agency that regulates broadcasters.

Yanardag had been one of the loudest critics of Erdogan’s government, notably during the February earthquake disaster in which more than 55,000 people died and the May elections.

His arrest is part of a trend, observers say.

“There has been a steady increase in the number of press and media freedom violations reported from Turkey in recent years, and it appears to be gaining momentum in relation to the political situation and polarisation in society,” said Ozturan.

“Following the earthquakes in February, after persistent targeting of journalists by state and government officials, the number of journalists subjected to physical violence increased dramatically and we reported multiple severely violent cases.”

“Multiple journalists also became targets of the Disinformation Law which came into effect in October 2022,” he said, referring to a much-criticised law that criminalises the intentional spread of ‘disinformation’. “The period leading up to the elections also saw an increase in the number of articles and journalist accounts that were being blocked.”

Worst yet to come?

Under Erdogan, Turkey has become one of the world’s biggest jailers of journalists, but it also puts media under pressure by other means such as court cases, fines, and closure.

A report published in June by Germany’s Friedrich Naumann Foundation for Freedom said that Turkey was copying Russia’s ‘playbook’ by using the judiciary to silence critical journalism.

According to another report from Turkey’s Media and Law Studies Association, 87 per cent of Turkish journalists say they do not feel safe while doing their jobs.

Media watchdog Reporters without Borders, RSF, this year ranked Turkey 165th out of 180 countries on its index of press freedom.

Many predicted that such repressive measures would intensify after an Erdogan victory.

“Newspapers may be closed, more journalists imprisoned,” Dogan Senturk, managing editor of FOX TV, the most popular broadcaster, said on May 24, days before the presidential run-off won by Erdogan.

“It would not be a surprise if newspapers are censored, more journalists are detained and imprisoned for their reports, as happened in the past,” he was quoted as saying by the Turkish daily Cumhuriyet.

The latest victim is investigative journalist Baris Pehlivan, who was put behind bars on August 15 for a fifth time. Pehlivan was convicted over his reporting in March 2020 on the funeral of a Turkish intelligence officer in Libya and spent six months in prison before being released on parole in September 2020.

On August 2 this year, he wrote in a newspaper column that he had been summoned back to prison by SMS allegedly for breaking the rules of his parole by ‘insulting’ a judge on Turkey’s Supreme Court of Appeals. Under sentencing laws, he has eight months of the original sentence of three years and nine months still to serve, but lawmakers in July adopted a new measure regulating parole and probation, according to which, Pehlivan’s supporters argue, he should remain free.

Turkish and international media organisations have condemned Pehlivan’s repeated imprisonment as harassment.

“Why can’t I benefit from the law enacted by the parliament of this country?” Pehlivan told reporters as he entered prison.

With Erdogan determined to wrest back control of Turkey’s major cities after they fell to the opposition in 2019, Ozturan said worse may be still to come.

“We are still concerned about what the coming months might bring, considering Turkey is heading into local elections in March 2024.”