Veteran Turkish journalist Merdan Yanardag was sentenced to two years and six months in prison on Wednesday for “making propaganda for a terrorist organisation” following his criticism of the jail conditions of Abdullah Ocalan, leader of the outlawed Kurdistan Workers’ Party, PKK.

Despite the sentence, Yanardag was released from prison considering he had spent more than three months in prison already.

“I criticized the policies followed by the [ruling] Justice and Development Party. They came to a conclusion that I praised Ocalan, for no reason. Why did you arrest me?” Yanardag asked on Wednesday in a press conference in front of Marmara Prison, formerly known as Silivri Prison, which is famous for holding political prisoners.

“This prison is the symbol of the regime’s tyranny,” Yanardag added.

Another senior journalist, Aysenur Arslan, was taken into police custody and investigated by prosecutors’ office for her comments on last Sunday’s Ankara bombing, which was claimed by the PKK.

Arslan was accused of praising terrorists. Both Arslan and Yanardag were targeted by pro-government media and social media trolls due to their comments.

“I explained what I really said [on TV]. As a result, I was released,” Arslan said on Wednesday in front of the court house in Istanbul.

Turkey’s Radio and Television Supreme Council, RTUK, the government agency for regulating TV and radio broadcasts, has taken punitive measures against Halk TV, citing comments made by Arslan on the channel related to Sunday’s bomb attack in Ankara.

RTUK imposed five programme suspensions, deeming Arslan’s comments a violation of the rules. RTUK also imposed a 3-per-cent fine [of its revenues] on Halk TV for “crossing the line of criticism”.

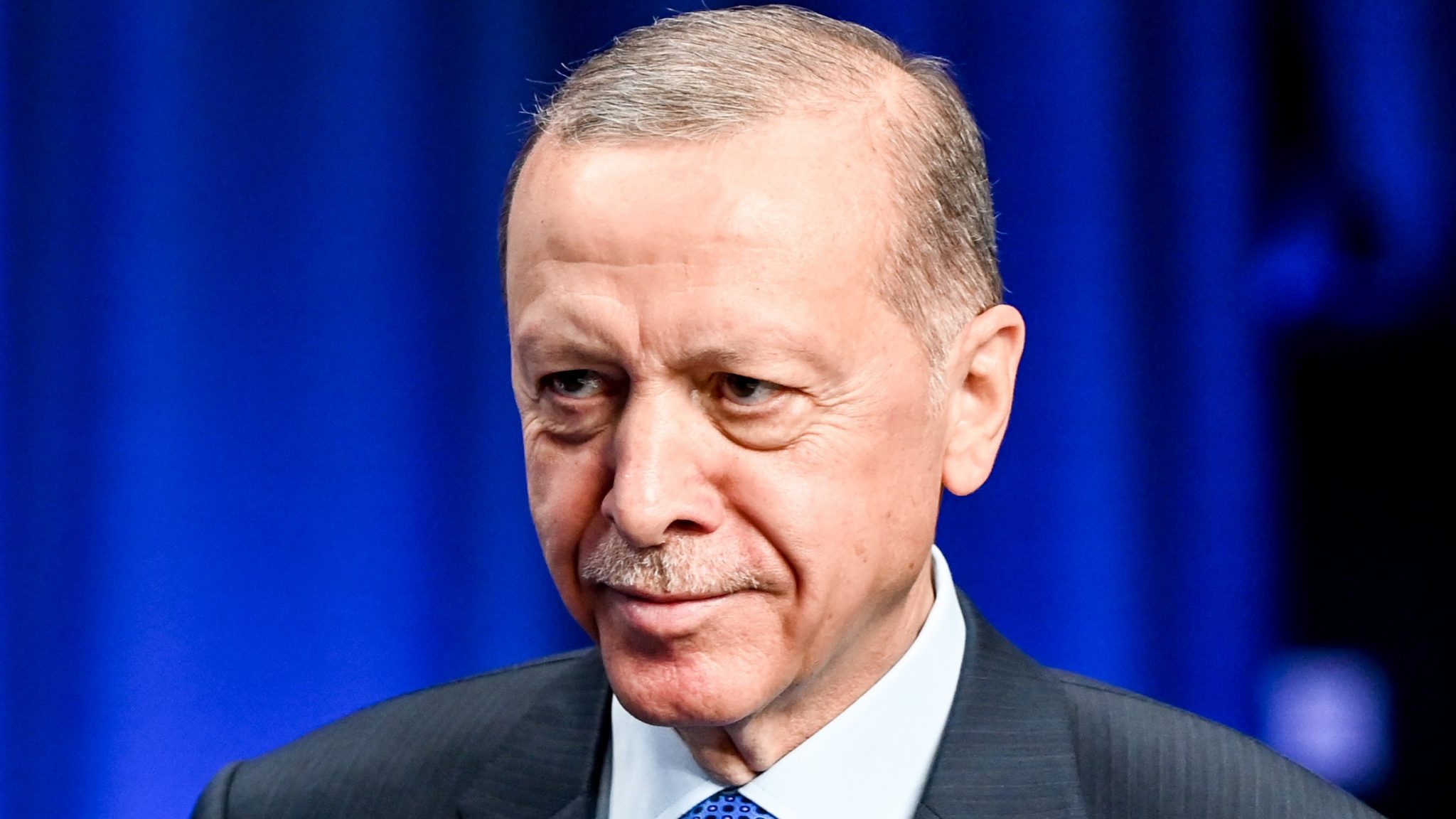

Yielding to the government of President Recep Tayyip Erdogan, Halk TV has since ended Arslan’s programme and fired her.

“Although terrorism was condemned in the same program, the unfortunate words spoken live in the … program aired yesterday go beyond the limits of Halk TV’s stance and perspective. Therefore, we announce with regret that we have decided to end the program,” Cafer Mahiroglu, chair of the Board of Directors of Halk TV, announced on Tuesday.

Following last Sunday’s bombing, Turkey has intensified its police and military operations against the PKK.

Since Sunday, the Police and Gendarmerie hsve arrested at least 105 people, and two more Kurdish militants were killed in clashes with the Gendarmerie in Agri province on Wednesday.

As the air force continues to bomb PKK targets in northern Iraq, the Turkish Defence Minister said that two of the bombers came to Turkey from parts of northern Syria controlled by the Kurdish People’s Defence Units, YPG, forces backed by the United States.

“We would like everyone to know that all facilities and activities of the PKK and YPG in Iraq and Syria are our legitimate targets,” Defence Minister Yasar Guler said.

Turkey considers the YPG a sister organisation of the PKK.

However, Mazloum Abdi, the leader of the YPG, denied playing any role in the bombing.

“Ankara’s attack perpetrators haven’t passed through our region as Turkish officials claim, and we aren’t party to Turkey’s internal conflict, nor do we encourage escalation. Turkey is looking for pretexts to legitimize its ongoing attacks on our region and to launch a new military aggression that is of deep concern to us,” Abdi said on Twitter on Wednesday. He added that Turkish attacks on cities are war crimes.

Doarsa Kica Xhelili, LDK MP. Photo: BIRN

Doarsa Kica Xhelili, LDK MP. Photo: BIRN