The US embassy in Montenegro has placed billboards on several locations in the capital Podgorica, offering up to $10 million for information on cyber attacks in Montenegro operated against American interests.

The billboards seek information about ransomware attacks on state information systems, interference in elections, or “malicious cyber activities against critical American infrastructure”. Montenegro has been part of NATO since 2017.

The announcement is written in Montenegrin and Russian and aims to attract “technologically skilled individuals who currently live in Montenegro and know about the attacks”, as the embassy in Montenegro told Radio Free Europe, RFE.

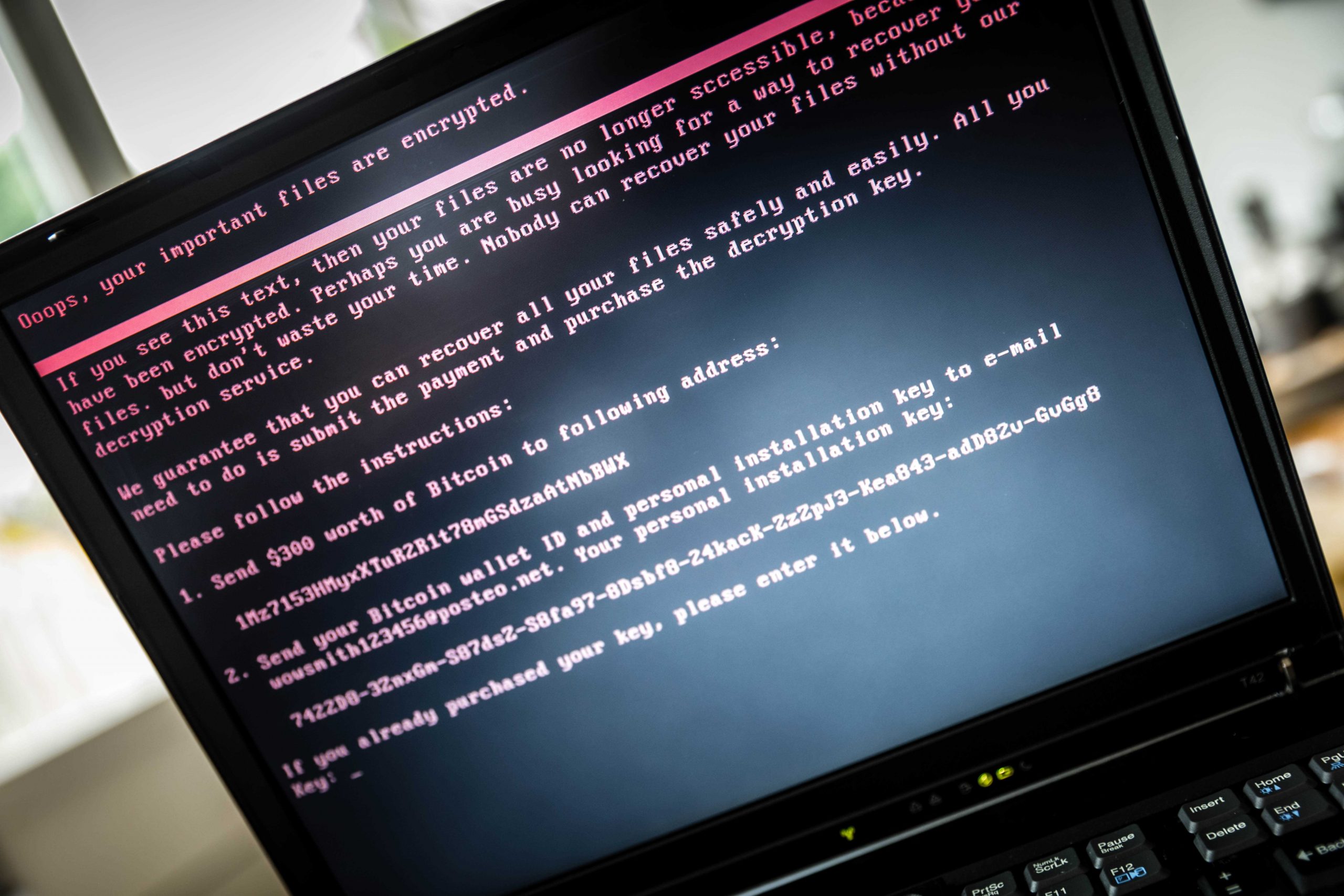

The billboards say that “’recent malicious cyber activities in Montenegro indicate the need to protect digital ecosystem”, likely referring to the cyber attacks from August last year targeting a host of government services in Montenegro.

Authorities in Montenegro still have no definitive answer as to who was behind the attacks which compromised various public services, including the websites of the government and the Revenue and Customs Administration.

In August last year, National Security Agency said Russia was to blame but offered no evidence. Then, the government stated that it was actually the work of a cybercriminal extortion group named Cuba Ransomware. In the end, authorities could not determine precisely who the perpetrator was, despite the assistance of the FBI and the French National Cybersecurity Agency, ANSSI.

The award is part of the U.S State Department program, “Rewards for Justice”, ongoing since 1984. The mission of the program, as stated by the State Department, is to protect Americans and US national security. It rewards information on terrorism, foreign-linked interference in US elections, foreign-directed malicious cyber activities against the US and activities that support North Korea.

Last year, a report by the European Bank for Reconstruction and Development, EBRD, characterized Montenegro’s “digital maturity” level as “basic” and recommended cybersecurity requirements for all digital service providers. Cybersecurity Ventures, one of the world’s leading publishers in the field, predicts the annual cost of global cybercrime will reach $10.5 trillion by 2025, up from $3 trillion in 2015.