Using new spyware technology as well as bugs and wiretaps, authorities in various Central and South-East European countries continue to monitor reporters and their sources, journalists who have been under surveillance told BIRN.

“Oh my God, I was monitored, what did they have access to?”

This is what Hungarian investigative journalist Szabolcs Panyi thought to himself back in 2020, when he and his colleagues were working on a report about a leak of tens of thousands of phone numbers of people who were under surveillance, using high-tech Pegasus spyware that infects mobile phones.

One of the numbers on the Pegasus list was his own. Panyi found himself in the unusual situation of being one of the victims in the story he was investigating.

“I didn’t have much time to think about it, because I had to work on the story and I had to talk to others who were in a similar situation. So, it actually helped me in processing the whole thing, because I could see that it wasn’t [just] directed against me, I was just part of a much bigger picture,” he told BIRN.

This bigger picture is made clear by BIRN’s survey of 15 countries in Central and South-East Europe, which identified 28 cases of surveillance of individual journalists or larger numbers of journalists over the past decade. It’s not clear how many more remain undiscovered and how much active surveillance is still ongoing.

Based on interviews with journalists who were targeted and research into other cases, BIRN was able to establish that:

- In the vast majority of cases, states are proven or suspected to be behind the surveillance.

- Surveillance operations do not only target high-profile investigative journalists covering organised crime.

- Despite new spyware like Pegasus that targets mobile phones, ‘traditional’ types of surveillance, such as wiretapping or physical monitoring, are still the most popular methods being used.

- In almost two-thirds of cases, police or prosecutor’s offices have opened official investigations into the surveillance.

- None of the cases has resulted in a court verdict or in anyone being held accountable.

Investigators and judges are currently dealing with ongoing cases of surveillance against journalists in Greece, Moldova, Slovakia and North Macedonia. In North Macedonia, the country’s former secret police chief is awaiting retrial for the illegal wiretapping of thousands of people, among them journalists.

The spy in the phone

Hungarian journalist Szabolcs Panyi speaking to BIRN about how he was monitored. Photo: BIRN.

The UK newspaper The Guardian has described Pegasus as “perhaps the most powerful piece of spyware ever developed – certainly by a private company”.

Manufactured by Israeli cybersecurity firm NSO, it can be installed on mobile phones by exploiting their vulnerabilities and can then record or harvest messages, photographs, videos and calls.

An international investigation led by a non-profit media organisation, Forbidden Stories, established in 2021 that it has been used against more than 50,000 phone numbers in more than 20 countries around the world.

The data showed that at least 180 journalists have been targeted, in countries including France, Morocco, Mexico and India and Hungary.

Panyi, who works for Hungarian media outlets Direkt36 and VSquare, which had access to the Forbidden Stories data, said that, of these 50,000 phone numbers, there were “more than 300 numbers that we suspected the Hungarian user [of Pegasus], which we later learned was the Special Service for National Security, had selected for surveillance”.

Panyi also uncovered the fact that Hungary had spent at least 6 million euros of taxpayers’ money on procuring Pegasus spyware in 2017-18.

He noted that because Pegasus is so invasive, “this type of surveillance violates someone’s privacy rights in a way that can only be justified if someone committed a very serious crime, or there is a very strong suspicion of this type of crime”.

“And what we have seen is that there are dozens of people who appear in this list with their phone number who have not been prosecuted in any way, who are not involved in any suspicious activity,” he said.

The Pegasus spyware was able to exploit vulnerabilities in mobile phones’ operating systems, installing surveillance applications and programs that turned journalists’ phones into listening devices.

Pegasus and other spyware programs, such as Predator, can infect devices via so-called ‘zero-click’ attacks, which can infect phones without the user’s involvement. They can also install malware through links sent to phone users. One such link was sent by text message to the Greek investigative journalist Thanasis Koukakis in July 2021.

“Thanasis, do you know about this issue?” the message said, containing a link that, according to Koukakis, suggested that it was “a piece of banking news”.

“I clicked on the link and at that moment I was basically infected with Predator, and they had access to my mobile until September 24, 2021, for two-and-a-half months,” he told BIRN.

Predator is a type of spyware similar to Pegasus but created by a company called Cytrox in North Macedonia.

Koukakis started to suspect something was not right when he noticed that his phone was overheating and its battery was “dying too fast”. He started to check with his sources and eventually got in touch with Citizen Lab, an internet watchdog organisation at the University of Toronto, which helped him prove that he was under surveillance.

The use of spyware may be more widespread than has been documented. In December 2020, Citizen Lab reported that Serbia’s Security Information Agency, BIA, uses software from the Israeli company Circles – part of the NSO Group that produced Pegasus – which enables the user to locate every mobile phone in the country in seconds.

So far, it has not been confirmed that the software, which Citizen Lab believes over 20 other countries have acquired, has been used to target journalists.

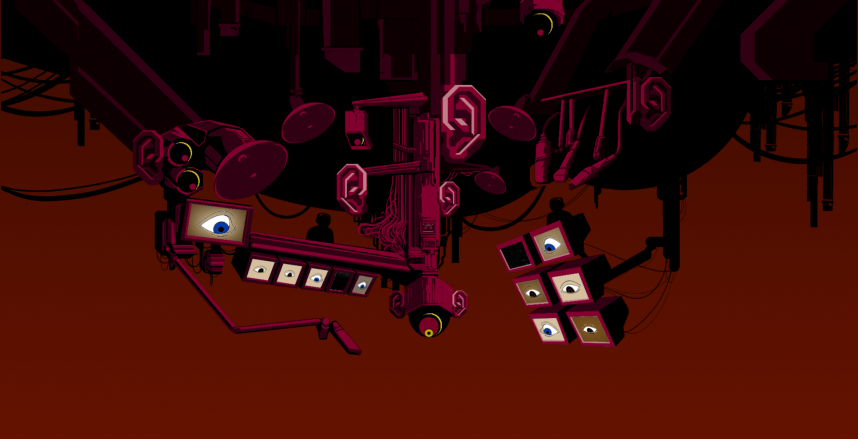

‘Traditional methods’: cameras and bugs

Photo illustration: Unsplash/Denny Müller.

Although the use of digital surveillance has increased over the years, ‘traditional’ methods are still more commonly used to monitor journalists, according to BIRN’s findings.

State authorities trying to find out about journalists’ sources or uncover compromising material mostly use wiretapping and physical surveillance: bugging phones and apartments and following people on the streets.

These methods are sometimes used on their own but more often as a part of a package of surveillance measures in which journalists are simultaneously followed and their conversations are recorded, or their devices monitored.

In February 2020, Romanian journalist Alexandru Costache, who works at the country’s public broadcaster, TVR, spent an evening at home socialising with friends who included journalists and judicial officials. The next morning, Costache got a call.

“A friend called me: ‘Turn on the TV, turn on RTV [Româniă TV], look what’s on RTV.’ It was us,” Costache told BIRN.

A subsequent investigation established that 11 people were involved in recording Costache and his friends’ conversation, mainly in the room where they met, “but also in the hallway towards the toilet, we were even filmed and photographed inside the toilet, as well as outside, in the yard, on the street”.

“They followed me until I got home, because I live nearby,” he added. The people carrying out the surveillance were posing as journalists for an online media outlet.

The Bucharest Military Prosecutor’s Office launched an investigation but the culprits were not identified and the case was dropped earlier this year. The specific reason for the surveillance remains unknown.

The use of spyware has been documented in several European Union member states, including Greece, Hungary and Poland.

Ricardo Gutierrez, general secretary of the European Federation of Journalists, EFJ, told BIRN that he hopes that the EU will ultimately take action to curb the activities of member states that spy on journalists, by “not allowing governments to use Predator, Pegasus and that kind of tool against anyone, not just journalists”.

“It’s very important to understand that if you allow such surveillance of journalists, then it means that everybody can be under surveillance tomorrow,” Gutierrez said.

Old tactics persist in post-Communist states

Serbian journalist Stevan Dojcinovic. Photo: BIRN.

The majority of the Central and South-East European countries surveyed by BIRN were formerly ruled by Communist regimes that used surveillance widely. During the post-Communist transition period, the security services in some of these countries were not fully reformed.

In Serbia, after the fall of authoritarian President Slobodan Milosevic in 2000, the security apparatus continued to use many of the same methods, including using compromising material obtained by subterfuge.

“Sado-masochistic French spy!” was just one of the front-page headlines in the government-affiliated tabloid Informer targeting Serbian investigative journalist Stevan Dojčinović in 2016.

Dojčinović said the tabloid’s sensationalist report was a part of a campaign against him that was launched when his investigative media outlet KRIK (Mreža za istraživanje kriminala i korupcije) investigated a property owned by then Prime Minister Aleksandar Vučić, who is now the country’s president.

The headline referred to explicit photographs published by Informer that showed Dojčinović participating in a private ‘suspension bondage’ event attended by seven or eight people.

Dojčinović said that the Serbian intelligence service, BIA, thought it could “destroy” him with the publication of the explicit photographs, showing that it “still has that Communist old-school brain” that relies on targeting people’s private lives to exert pressure.

He decided to bring a case against Informer for breach of privacy – and his lawsuit revealed that the BIA was behind the smear operation.

“When I sued [the tabloid], in the response to the lawsuit their lawyer wrote that everything I said wasn’t true, and then he said that all the information that was published [by Informer] was correct and that in order to confirm the information, the court should address the BIA,” Dojčinović recalled.

“That way, they essentially gave me the first bit of material that I could get in order to initiate some further processes against the BIA,” he added.

Dojčinović brought a complaint to Serbia’s Ombudsman. The case is still in progress.

‘The scale of monitoring was enormous’

Alena Zsuzsova at a preliminary hearing at the Judicial Academy building in Pezinok, Slovakia in December 2019, before her trial over the murder of journalist Jan Kuciak and his fiancee Martina Kusnirova. Photo: EPA-EFE/JAKUB GAVLAK.

In the digital era, surveillance isn’t only carried out by intelligence services, domestic and foreign, but by companies and criminal organisations, too.

One of the most notorious cases of surveillance of journalists in Europe in recent years was instigated by private individuals, and culminated in the killing of a reporter.

Marian Kočner, a powerful Slovak businessman with political ambitions, recruited a team of ‘spy commandos’ – a group of former police and intelligence agents, to spy on various people, including eight prominent journalists, to uncover their “dirty secrets”. This could then be used to blackmail or embarrass them via an online outlet he had set up called Na Pranieri, according to witnesses at a subsequent trial.

One of the journalists targeted for surveillance was Ján Kuciak, who regularly wrote critical investigative stories about Kočner’s business dealings for the Slovak news website Aktuality.

Kuciak and his architect fiancée, Martina Kusnirova, were then shot dead on February 21, 2018, at their home in Veľka Maca, some 65 kilometres from the capital, Bratislava.

The previous year, Kočner had threatened the reporter in a phone call, but although Kuciak had reported the threat, the authorities declined to investigate or call the businessman for questioning.

A Slovak court in May this year acquitted Kočner, after a retrial, of ordering the murders of Kuciak and Kusnirova.

“The court is convinced that the accused Kočner was worried about the journalist Ján Kuciak, especially at a time when he wanted to enter politics… [but] we cannot convict someone solely based on the motive,” judge Ruzena Sabova said in the original trial. Kočner’s associate, Alena Zsuzsova, was found guilty of ordering the killings.

As regards the ‘spy commando’ surveillance team, Slovak police in March 2019 initiated criminal procedures against ‘unknown perpetrators’ who had monitored the journalists and other people from early 2017 to May 2018, according to the Slovak Spectator. No indictment has yet been issued in the case.

But Laura Kellöová, an investigative journalist who continued to work on Kuciak’s reports at Aktuality, after he was murdered, said she was shocked at the intensity of the surveillance: “The scale of the monitoring of journalists and the illegal extraction of information about them from police databases was enormous.”

“I thought that this kind of thing had ended in Slovakia after the end of Communism,” Kellöová said.

‘It’s not part of the job’

Greek journalist Thanasis Koukakis. Photo: BIRN.

The majority of the journalists who spoke to BIRN about their experiences of being monitored said they were more worried about whether the surveillance could have affected their contacts or revealed details of stories they were investigating than about the impact on their own personal lives.

“What concerns me very much is how much my sources have been affected, the people with whom I was in contact during the period I was under surveillance,” said Thanasis Koukakis, financial editor at CNN Greece and Newsbomb.gr, who was monitored by the Greek National Intelligence Service in 2020, and with Predator spyware a year later.

Koukakis said that, because of the surveillance, some of his sources in the Greek finance ministry and banking system were moved from sensitive positions without explanation. “In retrospect, of course, it all makes sense,” he said.

EFJ general secretary Gutierrez said that journalists often display two problematic tendencies when it comes to surveillance. One is thinking that they’re not covering “important issues”, so they would never be put under surveillance; the other is thinking that being monitored by the authorities is just part of the job.

“No, it’s not part of the job to be under surveillance, it’s not part of the job to be arrested and it’s not part of the job to be intimidated,” Gutierrez asserted.

Police or prosecutor’s offices launched official investigations into the incidents of surveillance in under two-thirds of the 28 cases analysed by BIRN.

None of these cases has resulted in a court verdict so far. In almost half the cases in which an investigation was launched, the probe is still ongoing.

One such unresolved case is the mass wiretapping uncovered in North Macedonia in 2015, which allegedly involved senior police officials. The secret police chief at the time, Saso Mijalkov, was convicted of involvement but in 2021, the appeals court overturned the verdict and Mijalkov is awaiting a retrial.

According to the charges, between 2008 and 2015, when the country’s authoritarian Prime Minister Nikola Gruevski was in power, the defendants illegally tapped more than 4,200 telephone numbers without obtaining court orders. Many of those who were bugged were journalists.

One of those whose phone was tapped was the prominent journalist Vasko Popetrevski, editor-in-chief of ‘360 Degrees’, a television show and website.

After an investigation started, after Gruevski’s government was ousted, Popetrevski found out that “literally day and night for seven-and-a-half years, all my phones were being listened to 24 hours a day”.

He is hoping that Mijalkov will be convicted under a final verdict before the statute of limitations expires in his case in 2025, and that the victims of surveillance will receive compensation – “as a message that this should not and must not happen again”.

‘Abusive use of national security’

Photo illustration: Unsplash/Camilo Jimenez.

Some journalists who have been tapped, bugged and followed told BIRN that they now take greater precautions to avoid being monitored, particularly considering the increasing sophistication of electronic surveillance.

Koukakis said he uses encrypted apps on his phone and tries to meet contacts face-to-face, if he can.

“And, of course, my cellphone is checked regularly to see whether it is free of spyware or not,” he added.

Bartosz Węglarczyk, editor-in-chief of ONET, Poland’s largest online news platform, who was put under surveillance in the late 2000s, said his media company employs digital security professionals to protect journalists from surveillance, working under the supposition that it could happen again at any time.

“We know it’s happening. So that’s how we act,” Weglarczyk said.

At Aktuality in Slovakia, Laura Kellöová expressed a similar view: “I always have to assume that someone might be listening in or watching me and has an interest in finding out who I’m communicating with, what I’m working on, who I’m talking to and who my sources are.”

Kellöová said that after the murder of Ján Kuciak, Aktuality’s journalists “communicate almost exclusively through encrypted applications, not through regular phone lines”.

But some European countries have considered expanding their security services’ surveillance powers since the start of Russia’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine, in reaction to perceived threats from Russian espionage.

In Poland, a draft law on electronic communications intended to give the security services access to any material sent or received by email or other online communication tools is awaiting approval from parliament.

Simultaneously, the European Union is exploring the possibility of restricting digital surveillance with the proposed European Media Freedom Act, the first ever regulation of media freedom at EU level, which is currently in the process of adoption.

However, based on the draft legislation and the European Council’s position on the law, it appears that this opportunity to curb digital surveillance is likely to be missed and the situation may actually become worse.

Gutierrez explained that, following intervention by France, the draft legislation has been changed to allow surveillance of journalists, if there is a “need for the state to ensure national security”.

The EFJ is worried about the possible “abusive use of this concept of national security to impose surveillance, to spy on journalists”, he said.

“It’s a kind of legalisation of spying on journalists for any reason because, you know, anything can be interpreted as a national security issue; it’s vague, so it’s easy for states to try to justify that kind of thing,” he warned.

Many of the journalists and experts who spoke to BIRN were convinced that, despite the cases that have been exposed and the subsequent legal challenges, the monitoring of reporters continues across Central and South-East Europe.

Saška Cvetkovska, editor-in-chief of the Investigative Reporting Lab in North Macedonia, noted that despite ongoing prosecutions of former officials for the mass surveillance scheme that was uncovered in 2015, material apparently obtained by wiretapping continues to be published.

“Daily, non-stop, from 2015 to today, unauthorised recorded conversations of presidents of political parties, businessmen, MPs and journalists have been appearing on various [online] platforms and in the media,” Cvetkovska said.

Hungarian investigative reporter Szabolcs Panyi, who discovered that he was being monitored with Pegasus spyware, said he also believes that surveillance is more widespread than so far revealed – and that the way the authorities and the general public have responded to reports that journalists have been monitored is also concerning.

“The whole reaction of the Hungarian state doesn’t show that they take the privacy, legal and human rights concerns that come up in this kind of surveillance seriously, but try to sweep it all off the table as a political scandal,” Panyi said.

“And the very, very sad thing is that I don’t see that Hungarian public opinion, Hungarian society itself, is showing any particular resistance when confronted with information that the Hungarian state can monitor anyone at any time.”

The interviews for this article were conducted by Claudia Ciobanu, Katarína Kozinková, Delia Marinescu, Sinisa Jakov Marušić, Eleni Stamatoukou, Milica Stojanović and Zita Szopkó.

See all the interviews for BIRN’s Surveillance States project, which examines the monitoring of journalists in 15 countries in Central and South-East Europe, on our special focus page.