Among the evidence gathered against a notorious Serbian crime gang rounded up in February were gruesome photos sent via an encrypted messaging app popular with drug smugglers. The downfall of Sky ECC and EncroChat has been a boon for police in Europe and the US, but raises a host of questions going forward.

When Serbian police arrested the leaders of a notorious crime gang in the first few days of February this year, in the search for evidence they seized 44 mobile phones equipped with an encrypted messaging app created by Canada-based Sky ECC.

Sky ECC described itself as “a global leader in secure messaging technology”, helping to keep a host of industries safe from identity theft and hacking. Law enforcement authorities in the United States and Europe, however, say it was created with the sole purpose of facilitating drug trafficking and had become the messaging app of choice for transnational crime organisations.

Using equipment that President Aleksandar Vucic said Serbia had “borrowed from friends”, police managed to access the app. What they found was gruesome, and damning – photos of two dead men, one of them decapitated.

Led by Veljko Belivuk, the gang – part of a group of violent football fans – is suspected of drug trafficking, murder and illegal weapons possession.

Belivuk and his associates, who remain in custody but have not yet been charged, allegedly used the app to organise criminal activities, and to brag about their exploits. In this, they were not alone.

On March 9, three days after Vucic displayed the photos, police in Belgium and the Netherlands made what Europol described the next day as a large number of arrests after secretly infiltrating the communications of some 70,000 Sky ECC devices and, from mid-February, reading them ‘live’.

On March 12, US authorities indicted Jean-Francois Eap, chief executive officer of Sky Global, the company behind Sky ECC, and Thomas Herdman, a former high-level distributor of Sky Global devices, accusing them of conspiracy to violate the federal Racketeer Influenced and Corrupt Organizations Act, RICO. Eap issued a statement denying any wrongdoing.

Critics of the government under Vucic say Belivuk had long acted with impunity, protected by reported ties to a number of senior governing officials.

Serbia boasted of a “war” on organised crime. But the timing of Belivuk’s arrest and the operation against Sky ECC raises fresh questions about what preceded the Serbian police swoop – whether Serbia acted alone, or was prompted to do so by evidence unearthed elsewhere.

Either way, the downfall of Belivuk and Sky ECC has shed new light on the lengths Balkan crime gangs have gone to evade surveillance, and the challenge facing authorities to strike back. It has also fuelled talk of the need to criminalise such software, raising alarm among some who say this would punish legitimate users, from political dissidents to investigative journalists.

The Serbian Interior Ministry and Security Intelligence Agency, BIA, did not respond to requests for comment.

“Organised crime groups from the Balkans have adapted quickly and cleverly in recent years to innovate and use technology to their advantage,” said Walter Kemp, director of the South-Eastern Europe Observatory at the Global Initiative Against Transnational Organised Crime.

While some still carry cash across borders or use wire transfers, others are using encrypted communication tools, laundering money through cryptocurrencies and elaborate financial schemes and branching into cyber and cyber-enabled crime, Kemp told BIRN.

“But while criminals are first-movers and quick adapters in using technology, law enforcement agencies are lagging behind.”

This message will self-destruct

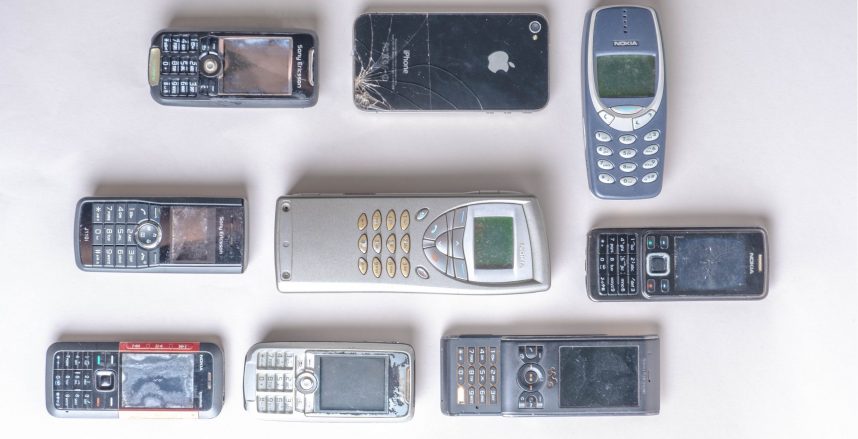

Screenshot: skyecc.com

Founded in 2008, Sky ECC surged in popularity after messages sent via another encrypted messaging service, EncroChat, were intercepted and decoded in a French and Dutch-led operation in mid-2020, leading to the arrest of over 800 people Europe-wide and the seizure of drugs, guns and large sums of suspect cash.

Sky devices offered self-destructing messages, an encrypted vault and a panic button in the event the user believed the device had been compromised. Sky ECC was installed exclusively on secure devices from Apple, Google and Blackberry, which could be bought online. All that was required of a user was to pay a subscription.

At the time of the police operation, three million messages per day were being sent via Sky ECC. Roughly 20 per cent of its 170,000 users were in Belgium and the Netherlands, with the greatest concentration in the Belgian port of Antwerp, a popular destination for illegal drugs arriving in Europe from South America.

Europol, the European Union’s police agency, said that information acquired from “unlocking the encryption” of Sky ECC would help solve serious and cross-border organised crime “for the coming months, possibly years.”

For Balkan clients, there were three websites promoting the app in languages of the region – skyecceurope.com, skyeccbalkan.com, skyeccserbia.com.

It is unclear if these operated under the umbrella of Sky Global or were independent distributors. BIRN contacted them but did not receive any reply. The website of Sky Global is also now in the hands of authorities. BIRN was unable to reach the company for comment.

Serbian nationals arrested in France and UK

Sky and EncroChat devices were, until recently, easy to find on Serbian and Croatian advertising sites, their price ranging from 600 euros to 2,200 euros depending on the type of phone and subscription. Subscriptions were commonly paid with cryptocurrency, to avoid leaving a trace.

A police official in Bosnia and Herzegovina said they were also in use among criminals there.

“They use those special apps and providers you can’t interfere with, and there’s no trace of their existence in the phone. The use is legal here,” the official, who declined to be named, told BIRN.

While police were unable to intercept the communication, he said, in some cases an arrested person would confess to using such apps and provide access.

A senior Interpol official, who spoke on condition of anonymity, said Balkan drug gangs were using EncroChat to communicate with South American cartels concerning the trafficking of drugs to Europe.

French authorities had been investigating EncroChat since 2017, stepping up efforts in 2019 and secretly installing an implant on all EncroChat devices disguised as a system update. The implant caused the device to transmit all data that had not been erased to a French police server and to Europol and collected data created after the device had been compromised.

The company eventually alerted users but millions of messages had already been intercepted.

Dutch and French police as well as Europol declined to give any further details regarding possible connections to Balkan crime gangs, citing the ongoing nature of the investigation.

A French newspaper report on March 27, however, said that a Serbian national had been arrested in a suburb of Paris following the Sky ECC operation on suspicion of selling its devices. In the UK, reports say another Serbian, 29-year-old Milos Bigovic, pleaded guilty in a UK court in August 2020 after he was arrested trying to smuggle cocaine hydrochloride into southern England on a cruise ship, his communications having been intercepted in the operation against EncroChat.

In Serbia, some criminals went further; in 2019, when police busted a major marijuana farm that had been run with the help of several security service officials, investigators found that those involved had communicated via a custom-made app called ‘Razgovor’ [Conversation].

Those arrested handed over their phones, apparently confident that police would not discover the app hidden behind the calculator interface. They were wrong and police, according to the indictment, gained access to conversations in which the suspects agreed on the production and distribution of drugs.

Admissible in court

Members of Veljko Belivuk’s group are being transferred for interrogation with a strong police presence. Photo:mup.gov.rs

It remains unclear whether foreign authorities supplied Serbia with evidence against Belivuk and Co obtained as part of the operation against Sky ECC, or if Serbia only harvested content from the devices it seized in the arrests.

Bearing in mind that most of the content sent via Sky devices disappeared soon after being sent, it is doubtful police in Serbia were able to recover much from the seized devices.

Authorities in Serbia did not respond to BIRN’s questions.

In the case of intercepted communication, for it to be used as evidence in court the police must have had prior court permission to conduct surveillance. It is not known whether Belivuk and his gang were under court-sanctioned surveillance. BIRN asked the court but was told such information cannot be disclosed.

The issue came before a UK court in February, when appeals judges rejected an attempt to prevent prosecutors from using as evidence messages sent via EncroChat.

The case rested on whether communications had been intercepted by French police while ‘being transmitted’ by the device or while ‘stored’ on it. As the material had been extracted from the device itself and was unencrypted, the Appeal Court found that the evidence had not been gained by ‘interception’ and was admissible, the BBC reported.

Criminalising encryption

Sky Global has denied any wrongdoing, with CEO Eap saying “We stand for the protection of privacy and freedom of speech in an era when these rights are under increasing attack. We do not condone illegal or unethical behaviour by our partners or customers. To brand anyone who values privacy and freedom of speech as a criminal is an outrage.”

But Serbian Interior Minister Aleksandar Vulin said the use of such devices should be illegal.

“It is indisputable that it is used by criminals,” Vulin said on March 7. “I am in favour of it being a crime, as I believe that the purchase of any telephone number, regardless of whether it is prepaid or postpaid, must be done with an ID card.”

“It may not stop criminals from using it, but if nothing else it will give the police another reason to arrest them and remove them from the streets.”

Some journalists and rights advocates say this is a slippery slope.

“Encryption is a tool. And like any tool, it can be used for good and for bad,” said Fabian Scherschel, a freelance journalist, writer and podcaster who has covered the topic closely.

“We’ve already seen legislation against so-called ‘hacker tools’ massively backfire and threaten to criminalise the legitimate work of IT security specialists and journalists. I have a feeling this legislation could cause similar problems. It will also, most likely, make it easier to spy on the general populace, who has no intention of using encryption to hide criminal behaviour whatsoever.”

Diego Naranjo, head of policy at the Brussels-based advocacy group European Digital Rights, EDRi, said it was important to challenge the narrative that encryption is only used by criminals.

“As any other interference with human rights, an attack on encryption or privacy-enhancing technologies needs to be prescribed by law, necessary and proportionate to the aims to be achieved in a democratic society,” said Naranjo.

He noted that the EncroChat and Sky ECC cases had demonstrated that law enforcement agencies have ways to penetrate such communication.

“We may be already in the Crypto wars 3.0, and it is up to us to ensure that encryption is perceived as a tool to ensure human rights and not something only criminals use.”

Lidija Komlen Nikolic, Serbian Deputy Appellate Public Prosecutor, warned of the dangers of criminalising the use of such apps.

“The idea is to enable state authorities, the police, to be able to find evidence more easily for the fight against organised crime or any other type of crime,” Nikolic told N1 regional broadcaster.

“But there should not be the presumption that all of us, who have devices or have software that uses some kind of encryption, are potential perpetrators of a crime.”