As murders related to organized crime become more frequent in Serbia, while state institutions remained silent, we decided to determine how many murders in the country were connected to criminal groups.

So, we made a database, which we have called “The Black Book”. One goal was to show what the authorities were doing to solve such cases or prevent such killings from occurring.

The Black Book is a unique database, containing information on the total number of mafia killings that have occurred in both Serbia and Montenegro from 2012 onwards – and what the authorities have done to solve these cases.

The information in the database can be easily filtered; it is possible to search by different criteria, such as the place where the murder occurred, the time frame, and the stage of the prosecution investigation or court trial.

The reason for creating the database

The original idea was to collect data on criminal murders, analyze them and see what they show. We started working at the end of 2015, and at first covered both the current and previous year, so that we could compare the data and tell if the situation was getting better or worse.

By the time we decided to build a database, a year had passed, so we now had information for three years. To make the sample even more representative, we added two more years. In this way, the database became more relevant as it also shows if the rate of those murders is increasing or decreasing.

A few phenomena attracted our attention. One is that mafia killings have become more frequent, yet state institutions have remained silent. A key aim was to show what the authorities were doing to solve these cases or prevent these kinds of killings from occurring.

Mafia war causes a spike in killings

In the beginning, we didn’t think we would have enough material for the database, so our idea was to publish a feature story with infographics that would explain the data we had collected. We soon realized that the situation was more serious than we had thought.

The number of murders was constantly increasing because of an event that happened in 2015 when a mafia war erupted between the two major criminal clans originating from neighbouring Montenegro, known as the ‘skaljarski’ and the ‘kavacki’.

The original cause of this conflict, which took on incredibly large dimensions, was 200 kilograms of cocaine that went missing in Spain. The clans started fighting in Montenegro and Serbia, but also in some Western European countries where they also operate. Other important criminal groups from Serbia and Montenegro, we found out, then took sides in this war.

So, we knew the Black Book couldn’t be complete without covering Montenegro as well. Organized crime groups from Serbia and Montenegro have been linked for decades. They often work together, or, and, have the same smuggling channels, but sometimes they fight over territory and illegal businesses.

Some of the murders that happened as a result of this war were committed in unusual places. One man was killed in a prison yard while serving his jail sentence. Another was shot dead at a prison gate while waiting to visit his brother who was an inmate. Murders occurred in the middle of the day, in public places, on streets, squares, even in restaurants and cafés. We noted every murder that occurred.

The final decision to create the Black Book was made at the end of 2016. By then, the number of mafia hits in Serbia had escalated to 52.

We realized that we were not the only ones to notice both the importance of this topic and the frequency of murders. Colleagues from Radio Free Europe also expressed interest, so we joined forces on the project and split the job. RFE focused on Montenegro while we continued to work on Serbia. We brainstormed about the methodology, the visual look and the functionality of the database, but also on the information it should contain.

Choosing the right methodology

We started to collect data – news articles, police and prosecution press releases, and publicly available official documents. Information related to murders up to mid-2015 was collected from the media. From that point onwards, we started doing everything by ourselves.

To make the database relevant, we needed to agree on a methodology. We noted victims who had any criminal background. We also decided that murders had to be committed in mafia-style – using firearms or car bombs, even if the victim himself had no criminal background. It was also important what the authorities had to say about possible motives.

Choosing the methodology and compiling the list of murders, it turned out, was the easy part. Another decision was figuring out what data to use, and what was important for the readers, and for journalists and other researchers who would use the database as a source of information.

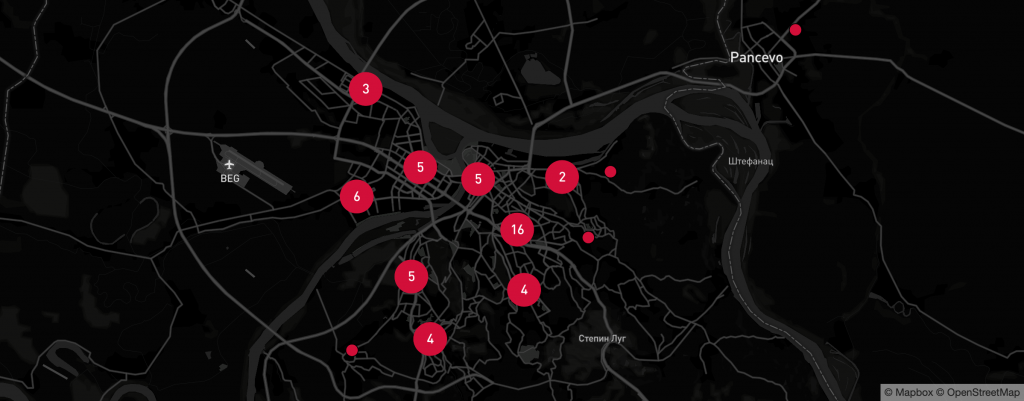

We realized it was necessary to include various things: the place of the murder – as this showed us whether the assassinations were more frequent in certain cities; a description of the incident; the age of the victim (there was a prevalence of victims under the age of 40); the way in which the murder was committed and the stage and progress of the investigation.

We decided also to compile several categories to show: what the prosecution and police had done; any unknown perpetrators; any possible suspects; on-going trials; case closures (final verdicts).

We needed to fact-check all the information collected from the media. In most cases, the media had already published the full name of the victim. If they didn’t, we had to figure out ways to identify the victim. One was to check the obituaries; almost every time we got full name and age of the murder victim.

We had to be sure also when and where the murder took place, check the person who was killed and get official information on whether the victim was convicted and, if so, for what crime.

In some cases, this was easy. Certain prosecution offices in Serbia answered our questions quickly. The situation was more complex with the prosecutors’ offices in Belgrade, where it is almost impossible to get such information quickly. Since most of the murders took place in the capital, we had a lot of work to do.

Besides investigating the victims, we had to monitor what was going on with the police investigations. By mid-2017, just before it was published, the database contained 80 killings. For each of them we asked the competent prosecutor’s office about the investigation and whether there were suspects or the trial had begun.

If the case was already before the court, using the Law on Free Access to Information of Public Importance, we asked for copies of the indictments. These gave us more details, such as, among other things, the way the murder was committed.

But because prosecutors and courts in some cases delayed delivery of the requested documents, this often took a while.

In the meantime, the number of murders increased, so we were working on new cases. In mid-2017, we were ready to publish the database. By then, we had recorded 83 murders and had collected all the necessary information about them.

Most criminal killings remain unsolved

The data were alarming; murders took place on average every three weeks and were often carried out in public places. The database showed also that the authorities were not solving these cases; there were only four final verdicts.

The Black Book has revealed that the lives of citizens of Serbia and Montenegro are endangered by these ongoing criminal conflicts. In two cases, innocent victims lost their lives. Other citizens were injured just because they found themselves at the wrong time and place.

After the database was released, we were attacked and our data was questioned. Senior officials tried to discredit our work. The Serbian Minister of Interior, Nebojsa Stefanovic, and the President, Aleksandar Vucic, both presented their own statistics, which, of course, showed the authorities in a better light – as successfully solving these cases. They also claimed the number of murders was decreasing.

But they forgot to mention that their statistics included all murders, not just mafia-related killings but also “crimes of passion”, caused by domestic violence, quarrels, and brawls.

They have tried to convince the citizens that they are safe. At the end of May 2018, the Minister of Police in Serbia insisted Belgrade was a safe city, even though 10 murders had occurred in the city that year.

It is a dispiriting fact that, since October 2016, when the state of Serbia declared war on the mafia, 37 more mafia-style murders have occurred.

Two years after the publication of the Black Book, the number of murders has risen to 147, of which 96 were carried out in Serbia. Only 9.5 per cent of these cases have been solved. The suspects remain unknown in almost 64 per cent of them.

A useful barometer of civic safety

Besides citizens, this unique database is also important for other journalists and researchers monitoring the level of citizens’ security in Serbia.

Its unique value has been recognized beyond the borders of this country. An MEP and Rapporteur for Serbia Ivo Vajgl used its data last year during a debate in the European Parliament on the latest draft report on Serbia, in order to raise awareness about this issue.

We, meanwhile, will continue to monitor the frequency of such criminal killings – and the willingness and ability of the state to solve them.