After weeks or sometimes months of thorough investigation, journalists often found themselves with a pile of documents and different materials used to support their thesis.

Once the story is written, it’s time to check if the journalists have proved their thesis by collecting the relevant information, speaking with sources and checking it all.

Journalists themselves are basically fact-checkers, as the whole investigative process is a process of checking and questioning all the claims, documents, etc.

However, fact-checking is not only a process of questioning proofs and claims but also the logic and the methods used in the investigative process.

A story is fact-checked and accurate only if the proofs are put in the right context and logically organized.

Fact-checking builds the credibility of the story, and of the journalists, and helps win the trust of readers. Moreover, it protects us from potential lawsuits.

So fact-checking is something that journalists should have in mind from the start of their investigation, and think of as an inseparable process from the investigation.

That means being aware of what can be used to prove a certain claim, what kind of source is credible and how to collect data in the right way.

Besides the journalist, a fact-checker is a person who is not involved in the investigating or writing process at all and gets access to the story after it’s already edited.

It is basically another editor who is giving the final remarks on the story and approves it before it can be published.

Important to note – fact-checking is not the same as legal scanning but is sometimes similar. Sometimes, even if something is accurate, a legal scan will show that it can’t be used in court as it might result in a lawsuit.

Every claim can be checked by asking two questions:

1. How do we know this is true?

2. What can I use to prove it?

What can be used as proof and how do we check it?

Documents

- Institutions – documents created by institutions, such as reports, statistics, rule books, etc.

- FOIA requests replies – statistics, reports, lists, etc.

- Private companies – documents from the business registry, their website, or provided by the company on request

- Public databases – business registry, assets registry, public procurements registry, stock market, etc.

- Data leaks – Big data. Documents leaked from an anonymous source, other media, online breaches, etc.

- Sources – official and anonymous. Documents provided by targets, victims, whistleblowers, public officials, etc.

How to check?

Documents issued by public institutions are often seen as accurate and trustworthy. However, they sometimes contain mistakes, are changed, or are falsified; we can only find that out by analyzing and checking. So, whenever possible, we cross-check one institution’s data with those of others. That way, we make sure that we avoid making false conclusions based on the official document.

Make sure to ask the relevant institution and the right questions when filing FOIA requests – and make sure to ask all the institutions that might have the data you need before you make conclusions.

If you’ve received a document from the source, a good way to check its credibility is to file an FOIA request, get a copy and compare them. If the institution refuses to deliver the document, you should try proving it is credible by facing the officials with that document, quoting the document in your questions, or by showing it to them. From their reaction, you may also conclude whether the document is valid.

When the source is anonymous, make sure to check the document with at least two different independent sources.

Audio and video footage (transcripts)

- Interviews – record all your calls and interviews. In most cases, we use audio recording just so we can have a more accurate quote and prove it to a fact-checker. If you’re recording phone calls, the audio cannot be published but used only as a proof of fact-checking.

Here’s the list of some of the best automatic call recorder apps.

How to check?

Ask your source if it’s OK to record before the start of the interview, and explain how you’re going to use it. Make sure you get the name and all the questions and answers on the record. Even though a journalist might have used the accurate quote, it’s important to check what the question was, and if it was used in the right contexts. Do not cut quotes as it suits you!

- Call records – save your listings to prove you reached or tried to reach the right person.

How to check?

Check the number you’ve used with the address book, phone on the website, or the number used by colleagues at your or other media. Be sure to check that the person is still using that number. In some countries, you may get a business phone of all the public officials if you file a FOIA request since those phones are paid from the budget.

Notes

- Interviews

- Observations

- Court hearings (when it’s not allowed to record)

How to check?

Be sure to write all the names and quotes right and catch as many details as possible. Cross-check with documents, databases and other media reporting to be sure you’ve got it right.

Photos

- Made by journalists

- Social media and Google

- Provided by sources

- Published on official web pages

- Other media

How to check?

Try to compare photos you’re using to prove something in your story with other available photos – who’s in the photo and what does it show? You may also ask relevant sources to recognize what’s on the photo.

When you’re taking photos, make sure also to catch the street, the building or something else that can be used to identify the location.

Check whether the photo has been published before by using reverse image search – use RevEye, TinEye.

Check if the photo has been edited: Image Edited.

You may also check the metadata of the image, so you can check when it was taken, what camera was used, etc. – Exif.

For photos found on social media, first, check the credibility of the social media account. If the account is verified, it’s more trustworthy.

You may try to prove its credibility by checking related accounts, website, tags, etc. When quoting social media, save screenshots showing when the post was published and when you took it, as the content might be removed by the time you publish the story. Always save the link to the page!

Address book

- Locations

- Companies

- People

How to check?

Use the phone numbers’ registry to show relations between people and companies by comparing the address and phone numbers. Often companies are registered at someone’s home or at their family address.

Sometimes a phone number or address will be the only contact available when we are searching for ordinary people.

Besides national Yellow and White pages, you may use the international platform NumberWay to search for numerous registries worldwide.

Screenshots

- Communication

- Web pages

- Social media

How to check?

Screenshots are sometimes the only way to ensure proofs for certain claims. A lot of information found online disappears, or later is removed or unavailable for various reasons. Screenshots are rarely published but are more often used as a way to prove something we mention in the story. The right way to make screenshots means including a date, URL, and a whole page that gathers the relevant information. Make sure to save a URL address with a screenshot as well, so you can link it in the story, and a fact-checker can then visit it if it’s still available.

The major problem with screenshots is that any page online can be changed, by changing the headlines, etc. The screenshot used afterwards will look as valid as the one taken on the real page.

For pages that are no longer available, you may use Google Cache or Wayback Machine for older content.

To save a page or search already saved pages, use a platform that allows you to save any online page, even if it’s been removed afterwards – Archive.fo.

Google maps

- Locations

- Check the surroundings

- Satellite view

How to check?

Make sure you’ve used the right address to show roots, check the satellite views, the distance, etc. You may also import the data from your sheets to create maps. Of course, prior to that, you have to check data used to create them, too.

Another useful cross-check platform to use, for example, while reporting about protests, is Mapchecking.com – it allows you to check how many people attended the protest, or debunk fake news.

Media reporting

- News

- Investigations

- Analysis

How to check?

The biggest problem with quoting other media is the risk of publishing false information. Sometimes, even the fact that 10 different media published the same thing doesn’t mean it’s true. When using other media reports in your own stories, the best method is to stick to media known for fact-checking methods, where it’s clear who the source of the information is. Do not use media reports to prove things you can find out on your own.

If the media is the only source available, provide at least three different articles on the same topic, all supporting the same claim, but only if the source is not the news agency, or if there is a video/audio available.

Also, always cross-check media reporting with your notes, documents and your sources’ claims.

Walking on the edge / common mistakes

- Common knowledge

“Everyone knows it, so there’s no need to check it!” Attitude is where mistakes often start – from what the average salary is to who the biggest minority in France is. Although it seems we know these things, as they’ve become part of an everyday narrative, that doesn’t mean they are true. There’s no such thing you may prove with the phrase: “It is known…”

- Dates

Different styles are used in different countries, so check which one is right and stick to one style for the whole story.

Make a timeline with the most crucial events.

- Names – people, company

Sometimes people and companies have the same name, so make sure to spell them right and try to identify them by ID/Business number, the address or the signature.

- Numbers

When scraping or gathering a lot of data, mistakes can happen. It’s not the same if it’s a million or a thousand. Make sure your method of counting percentages, averages, etc. was right, and that you’ve used the right format in your sheets. Always check twice, and use your computer to count it for you.

Check that you’ve used the same currency to count a total amount.

- Quoting other media

As mentioned previously, always try to get the information by yourself or check documents and other available sources.

- Photos

Make sure the photos you’re using are not edited and have a credible source.

- Outdated information

Make sure you have data for the relevant time period and that you’ve updated your story with the latest events. The investigative process is long and sometimes the story needs constant updates.

How to ensure efficient fact-checking?

- Data check:

- Dates – make sure you’ve checked all the dates and compared them to another source of information

- Spelling and duplicates – while working on databases or reporting about people, only one wrongly spelt name can change the whole story. Make sure you name all the people and companies properly. Don’t have any duplicates in your excel sheets/schemes/graphs.

- Context – statistical result alone is not relevant if it is not put in the right context. If there is a trend, you have to show how it changed through the years/months.

- Make sure your data is up-to-date. If you’ve worked on the story for months, check that you’ve collected data for the relevant period of time. Sometimes a lot can change from the moment we gather data at the start of our investigation to the point it is published. Avoid gaps in your data.

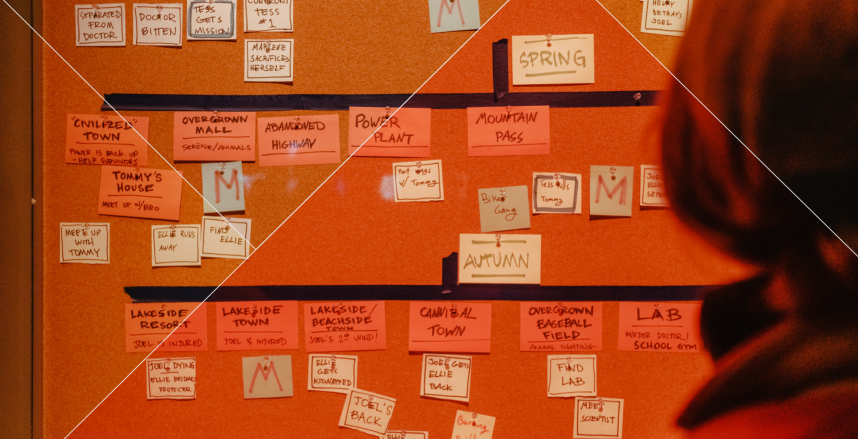

- Keep track of your activities and data. List what documents you have, what is pending, the interviews you’ve done, etc. It will help you keep track of covering all the aspects and plan activities easily, so you don’t miss anything.

- Explain the methods used – it gives readers the opportunity to question them. The better the method is explained, the less speculation there will be. Keep it short and simple.

- Question your thesis. Every day. The idea you had for the story might have changed with the latest discovery; it might kill your story, or take it in a completely different direction.

- Targets. People you’re writing about can be a great source of information and sort of a fact-checker as well. Face them with your data and ask for an explanation, there might be something you’re missing.

- Identify each fact in the story and list a document/file that proves it. It will help you check if you got all the conclusions right, and have it ready for your editor and a fact-checker as well.

- Use timelines for major events, so you don’t miss anything.

- Make folders and highlight important parts of the documents, so you can easily find them. To save time, make documents searchable.

- Use Excel, Google Sheets

- Save all emails, messages and calls. Keep them together with other material.

- Store all the material and keep it safe even after the story is published – in case of a lawsuit or a follow-up story.