Social media posts from the Ukrainian battlefields have been invaluable in enabling prosecutors in Serbia and Montenegro to prove the illegal military action of their nationals in Ukraine.

Marko Barovic was always on the wrong side of the law. Growing up in Montenegro, since his teenage years he always hung out with the bad guys.

Not even 30, he already has a conviction for robbery and attempted murder. Now, since April this year, he also has a conviction for taking part in a foreign military conflict, in Ukraine, which is forbidden by law in Montenegro.

Barovic is now serving his three year and six months long prison sentence.

In 2014, as warfare erupted in Ukraine between pro–Russian separatists in the east and Ukrainian fighters, many Russian sympathisers from the Balkans, mostly from Serbia, or Serbs from Bosnia and Herzegovina and Montenegro, joined pro-Russian paramilitary units operating in eastern Ukraine, mainly in the Donetsk area.

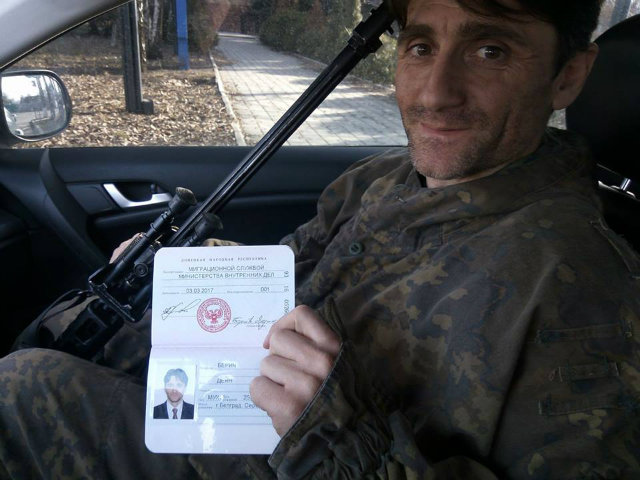

According to the court records, Barovic travelled in December 2014 to Russia, and then, just before New Year, to eastern Ukraine, where he got a military card from the self-proclaimed Donetsk People’s Republic.

According to the same military card, he served there initially as a driver and later as a sniper. In October 2015, however, he was arrested on the border between Ukraine and Russia.

Montenegrin prosecutors say the key proof that he fought in Ukraine and did not just drive a truck, as he claimed initially at the trial, was his Facebook profile.

He often posted photos from the battlefield of himself in uniform and holding a rifle. The posts and photos, which were public, were admitted as evidence before the court in Podgorica.

After being confronted with the evidence, Barovic confessed about he had really spent his time in Ukraine. However, he still defended his conduct. He said he had gone there to “help people for moral and patriotic reasons.”

Serbs flocked to help Russian ‘brothers’:

The verdict in April this year against Barovic was a landmark conviction in Montenegro, following the adoption of a law in 2015 that classified fighting on foreign territory as a crime.

In neighbouring Serbia, however, where the number of those who fought in Ukraine as foreign fighters was much higher, there have been no such trials, but only plea agreements.

Around 24 fighters who returned to Serbia last year from Ukraine admitted guilt after the prosecution produced evidence of their presence on battlefields.

Investigators mostly gathered this evidence also by examining their social media profiles.

Plea agreements are not public documents in Serbia, but BIRN sources from prosecutors’ offices say YouTube videos and Facebook photos proved the key evidence in most cases.

The most prominent case was against Radomir Pocuca, a former special police spokesperson, who over several months of fighting in Ukraine posted almost daily videos, photos and other entries related to his time in Donetsk.

Pocuca also claimed that he went to help Serbia’s “Russian brothers” for patriotic reasons, mainly as payback for Russia’s support for Serbia in the dispute over the former province of Kosovo [which declared independence in 2008 – which Serbia has vowed never to recognise].

Serbs also remember that Russian fighters volunteered for the Serbian side in the 1992-5 war in Bosnia, which pitched Serbs against a combination of Croats and Bosniaks [Bosnian Muslims].

For many of the Serbian fighters in Ukraine, this was not their first war.

Ranko Momic, who is believed to be still in Ukraine, escaped trial for alleged war crimes in Kosovo and fled to Donetsk in 2015.

A Bosnian Serb, he fought also in the war on the Serbian side in Croatia in the early 1990s, before taking part in the war in Bosnia, serving in so-called “special” units, such as the notorious Serbian Volunteer Guard.

Even during the 1990s, before mobile phones or social media appeared, these fighters enjoyed being photographed or filmed during their time in battle, and local and international courts used such records to secure convictions for war crimes.

Among the other better-known Serbian fighters in Ukraine with experience in the Bosnian war is Dejan Beric.

He was recently spotted again in the Donetsk area with a new group of Serbian snipers.

Beric was brought up in Putinci, a village in northern Serbia, where he ran a business making doors and windows in the nearby town of Indjija before closing his business in 2014 and leaving for Ukraine.

Many Balkan volunteers say they joined the rebels out of a deep sympathy with Russia and a sense of Slavic Orthodox Christian brotherhood.

But Beric said that he also went there after being personally invited by two Russian volunteers who previously fought in the Balkan wars in the 1990s.

“They called on me to repay the debt, in terms of moral and human spirit,” Beric told BIRN earlier this year in an interview.

Contrary to some accounts published on the internet, Beric said that becoming a volunteer is simple; would-be fighters need only to catch a plane to Rostov-on-Don in Russia and then take a bus across the border to rebel-held Donetsk or Lugansk in Ukraine.

“I came from Sochi, where I worked, via Odessa to Sevastopol, where I became a member of the ‘Defence of Sevastopol’… Then I went to Donbass,” Beric recalled.

Beric also regularly updates his Facebook and YouTube account with stories from the battlefield.

Many fighters remain on the run:

Social media profiles did not only help the authorities in Serbia and Montenegro to secure convictions; Ukrainian authorities have also used them to issue arrest warrants against the remaining Serbian fighters in the country.

Ukraine’s security service has issued arrest warrants against six Serbian mercenaries, while Kiev authorities maintain that almost 300 Serbs remain fighting in various rebel areas.

The six Serbs, according to Ukraine’s security service, fought in Ukraine in 2014 and then in Syria – another conflict zone in which Russia is deeply involved – in 2015.

All six allegedly belong to Wagner, a military company registered in Argentina, which the Ukrainian security service says serves as a paramilitary unit tasked with fighting for Russian interests across the world.

Among the six fighters wanted by Ukraine is Davor Savicic “Elvis”, a Bosnian Serb, who claims to live in Russia and work on a construction site.

Savicic was reportedly highly appreciated by his superiors at Wagner due to his extensive battlefield experience, and given the codename “Wolf” to reflect his strength and courage in combat.

While these claims could not be independently verified, Savicic’s Facebook profile picture is also, by coincidence, a wolf.

Bosnian police told BIRN that they believe that the mercenaries have a meeting point in Moscow, and that most of them are registered as temporary workers in Russia in order to avoid prosecution at home as foreign fighters.

Police records suggest that Savicic belonged earlier to various Bosnian Serb units, and spent the longest time fighting alongside the so-called Tigers, a notorious paramilitary unit led by Zeljko Raznatovic “Arkan”.

He who was killed in 2000 before he could face trial for war crimes by the international criminal tribunal for former Yugoslavia, ICTY, in the Hague.

In 2001, the Montenegrin prosecution accused Savicic and three others of planting a bomb in the house of Dusko Martinovic in the town of Berane, which killed six people. Martinovic allegedly owed them around 15,000 euros.

Savicic was initially jailed for 20 years in absentia in Montenegro, but an appeal court ruled later that there was not enough evidence to prove that he was responsible for the bombing.

From 2001 until his acquittal in 2014, Montenegrin police tracked him from Bosnia to France, Spain and Russia, but never managed to arrest him.

The same year Savicic was cleared, photographs appeared of him on the frontline in Lugansk, after he and an estimated 50 other Serbian fighters brought their battlefield skills to the aid of pro-Russian rebels against the Ukrainian government, according to the Bosnian prosecution.

Russia appears to have deployed them using similar methods to those Serbia used in the Bosnian war, when Serbia denied any direct involvement in the conflict and insisted all the Serbian citizens who took part in it were volunteers. Russia has done the same in Ukraine.

Wagner fighters have also fought for Russia’s Syrian ally, President Assad, and although many of them have denied the reports, news from Syria suggests that a number of them lost their lives fighting Assad’s jihadist foes.

Among them was Dimitrije Sasa Jojic whose death aged 25 was announced this June by the Serbian football fan group Firma, to which Jojic belonged before taking the path of a foreign mercenary.

Jojic also initially fought in Ukraine and had been active on social media there, posing in uniform and with other fighters.

It is believed that he was part of the same group from Wagner that went to Syria. Jojic was buried in Moscow this summer.

Other Serbian fighters, allegedly members of Wagner, and also wanted by Ukraine are believed to be stationed in Russia, travelling occasionally to rebel-held areas of Ukraine. All of them have Serbian or Bosnian passports.

Unlike Barovic or Pocuca – who were extradited from Ukraine and Russia – the Wagner men are seen as far more important for both sides in the conflict.

They are important for Russia, as their methods shed light on the hidden ways Russia exports fighters to the conflict zone.

They are equally important for Ukraine, which hold them responsible for numerous attacks that killed hundreds of people.

In consequence, as security experts have told BIRN, their extradition and arrest is highly unlikely.