Large data dumps are increasingly common, so journalists need to be able to extract the information needed to produce a story.

So, what do you do when you get a leak of 300GB of messy data?

Handling that amount of data is not easy and you need to know exactly what you want in order to manage it properly.

There are a few ways such data leaks come to you. Either a source gives them to you directly, as in the case of the Snowden leaks or the Panama Papers, or a hacker uploads it on the web as a set of files you need to download, as in the case of Hacking Team or the Silk Way Airlines files, which we used for our Pentagon investigations.

Or, maybe you just got a huge pile of paper documents you need to digitize in order to handle it properly, as in Yanukovych Leaks.

In any case, you need to act fast, especially if it’s something of immediate public interest, or your competition is on the case.

Your job is to quickly assess the material, organize it, recognize the significance of each document, verify it and start publishing.

But the first thing is to sort it all out and get to know the data.

It can be overwhelming, so you need to get on top of it as soon as possible.

- What did you actually receive?

- What does the source say and how does it compare to what’s in front of you?

- Does it look legit? Who can verify it?

- What’s the general content?

- Can you spot some leads?

- Is there anything you need to act on immediately?

When you get to grips with what’s actually in your hands, you work out what potential stories you might be able to extract from the data, then begin organising in such a way that you can prove or disprove your bias or story ideas.

A great example of this method is the work carried out by the researchers from The Share Foundation on the Hacking Team files.

Hacking Team, HT, is an Italian company specializing in software tools which can be used by cyber snooping. Reporters Without Borders labelled them as one of the corporate enemies of the internet. Hacking Team insists it acts responsibly.

In July 2015, an unknown hacker publicly provided the links to 400GB of internal files, invoices, email inboxes and source code of their software.

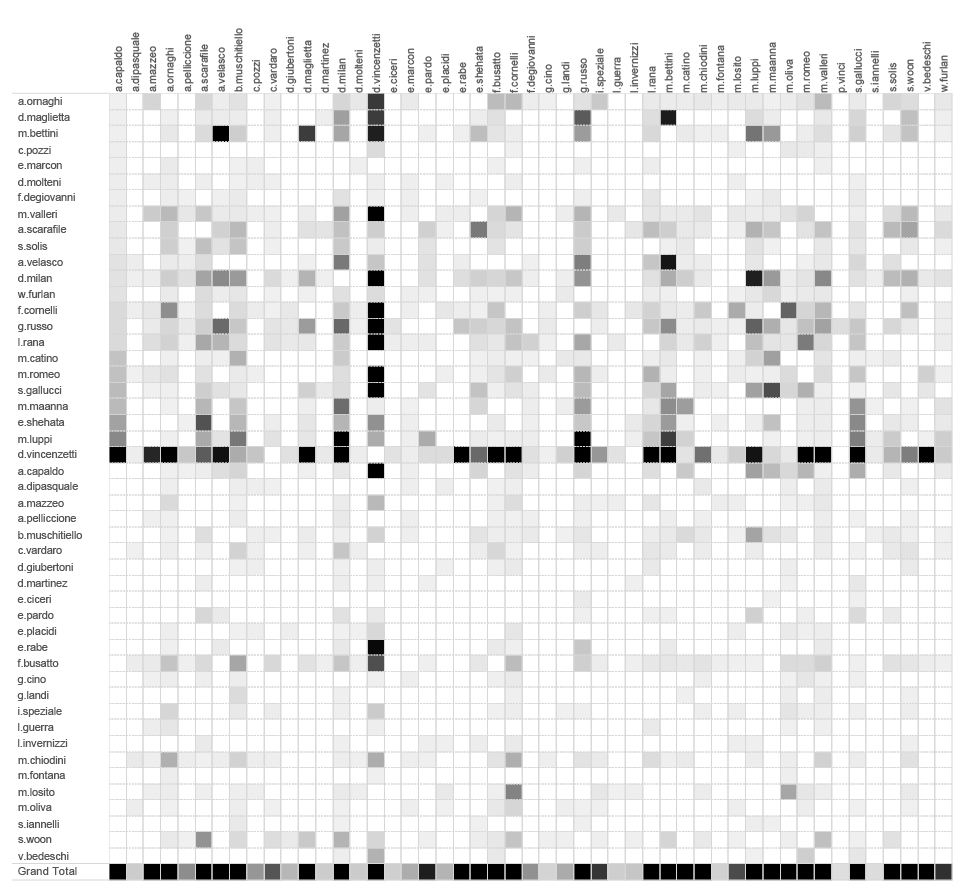

While everyone was focusing on HT’s contracts, their tools and countries involved, people from Share Foundation decided to do a story about the inner workings of Hacking Team, based on metadata from thousands of emails provided in the leak.

They managed to reconstruct the exact behaviour of HT’s CEO David Vincenzetti (Mister D.), what he was getting up when he was travelling abroad, when were crises occurred at HT and how he was behaving.

Investigating metadata is one of the main focuses of Share Foundation, so they formulated the main approach in their investigation accordingly: “We wanted to question а somewhat heretical argument that bulk metadata contains sensitive information about the private life of internet users.”

So, how did they do it?

First, they obtained the data provided by the hacker. Then they went through it, figuring out all possible stories, deciding on the one that was in their focus – the metadata investigation.

They realised that they could extract headers from hundreds of thousands of emails from HT mailbox accounts, and that’s when the story started to form.

When you know what you want, it’s just a matter of choosing the right tools to get it.

Email headers contain an enormous amount of data. Most of it is useless for a focused investigation, and you reporters need to make some sense of it.

For this type of investigation, the required data were: the subject of each email, the date and time, the email addresses of people involved and their names.

Since mailbox files had the extension .pst, that meant that those were files of Microsoft Outlook, the ubiquitous email software from Microsoft. However, Outlook was not of use in this investigation as its only job with emails is to open them and show the content.

They needed a tool to search through those files and extract and sort only the information they needed.

The tool they used was Outlook Export, a freeware program from Code Two that has several freeware programs for handling Microsoft files.

Using that, reporters were able to choose the metadata that was important for their investigation and export them into a separate table.

Now, when they had structured data in a table, it was just a matter of translating that data into a story.

But how do you translate hundreds of thousands of data rows into a story? How do you spot important trends?

There are several ways, but one of the best is to look at the data from a different perspective.

Using open-source visualization tools, such as the powerful but easy to use Gephi, reporters were able to graphically represent the extracted data in several ways.

Each representation gave them a new insight – who was communicating with whom inside the organization and outside, when would they went on holiday, when would they wake up, who was working from which part of the world, who were the main partners, etc.

That’s how they were able to identify the email address of the CEO as the central point in inner communications of the people in HT. This information defined the rest of the story.

By focusing on the CEO, reporters could answer the question they were asking: can you reconstruct a person’s behaviour based solely on metadata of their emails?

The answer was, yes.

By investigating metadata with only open source and freeware tools that are available to everyone, reporters were able to gain deep insight into the personal habits and activities of a CEO of a “hacking” company, and prove their premise that metadata contains sensitive information about the private lives of internet users that can be used to monitor the person’s behaviour “on a much deeper level than traditional surveillance”, as the reporters said in the conclusion.

This article was originally published in BIRN Albania’s manual ‘Getting Started in Data Journalism’